Why hitching currency redesign to CBN’s cashless policy isn’t as smart as it sounds

Our currency has been debased by and inflation is rampant because of the Central Bank’s unwillingness and/or inability to aim for and maintain stable prices.

Why then do we continue to ignore policy errors, while blaming our people’s love for holding cash? In truth, a comprehensive reform of our currency would have been a more fact-based response by the Central Bank to our current challenges. “Equivalent to about 30 cents, ought the N200 denomination to be a note or a coin?”, was how a friend who until recently taught Economics put this problem. As a coin, the N200 would better bear the vicissitudes of both rapid circulation and poor handling.

In the last four years, as the economy has plumbed new depths, a growing number of local commentators have turned their vast resources to understanding how economies work ― turning us all into experts of sorts. Nowhere has this new expertise found more fertile ground than in proffering solutions to our rising cost of living. Alas, with so many cooks in (and) headed for the macroeconomic kitchen, it is a scant surprise that the resulting policy broth is turning sour. How bad? And how quickly? One ingredient in this conversation around appropriate monetary policy has been implicated as responsible for our recently rancid domestic economic outcomes.

Reflection on the domestic money supply moved to the fore of our echo chambers when the Central Bank of Nigeria appeared to argue that we had too much of it outside bank vaults ― a little under N3 trillion as at March this year. From the central bank’s vantage, it was easy for the debate that followed to travel the route to blaming Nigerians’ love for cash as both the cause of so much money being outside the system and (by relentlessly chasing few goods) driving inflation up. Many of our talking heads have continued down this road into the most recent of the numerous cul-de-sacs that the country has been unfortunate to run. We are now at that point where the redesign of the naira is argued, in certain quarters, as an opportunity to curb the amount of currency in circulation, and thus address domestic inflation.

Also Read: Why write at all about Nigeria?

At which point, it bears repeating a quote from my contribution on this pages last week. If Ben Bernanke is right when he says “Currency in circulation is determined by the public’s choices, not Fed policy. For example, when people withdraw cash from their checking accounts to do Christmas shopping, the amount of currency in circulation automatically rises”, then cash in circulation simply reallocates the components of a country’s money supply ― it does not increase it.

In other words, an economy with less cash in circulation is no more or less prone to inflation than one with more, all other things remaining equal. For chequing accounts, or electronic cash for that matter, do not cease to function as money because the markets do not exchange banknotes or coins. Otherwise, the developed world would have entered a post-inflation era. For emphasis, at heart, this argument unravels into the proposition that inflationary pressures would be vanquished the more the streets use electronic money.

Myths aside, an increase in a country’s money supply (including its currency in circulation component) should, all other things being equal, lower borrowing costs and push up both lending to businesses (and households) and consumer spending. Ideally, both of these impulses should drive domestic output up. However, improperly functioning markets could drive prices up as part of this process…

This is not true. It is not simply counter-intuitive. The epidemic of inflation across the global economy means it is not also evidence-based. Unfortunately, much of what pretends to be deep thought on alternative responses to our current economic dilemma is erected on such myths and legends. So, let’s bust a couple of these myths. Number one: the currency in circulation component of Nigeria’s money supply has remained largely unchanged in nominal naira terms over the last six years. So, if we are looking for an excuse for inflation, it cannot be this. Myth number two: as a share of GDP, at about 6%, the amount of currency in circulation in Nigeria is no more nor less than in similar-sized economies. Indeed, in India, this figure stood at 13.7% in 2021-22. In the US it was about 10% last year. In 2019, it was 10.2% in France, 11.5% in Italy, 9.4% in Germany, etc.

Myths aside, an increase in a country’s money supply (including its currency in circulation component) should, all other things being equal, lower borrowing costs and push up both lending to businesses (and households) and consumer spending. Ideally, both of these impulses should drive domestic output up. However, improperly functioning markets could drive prices up as part of this process (or, especially, in spite of it), as the liquidity entering the market is wrongly allocated.

Also Read: Minting low denomination coins to fight inflation

Besides the happy circumstance when rising domestic productivity pushes output up, and the money supply increases because the naira may now buy more goods or services, money supply grows in three other main ways. The Central Bank prints money. Banks in the country lend more ― by holding less reserves. Or the Central Bank swaps its currency for convertible currencies to bolster its reserves. We know that the Central Bank has through ways and means advances (priming its presses literally) lent about US$48 billion to the Federal Government. We also know that those who put a cap in its enabling laws on the Central Bank’s ability to monetise the Federal Government’s deficit were alive to the inflationary consequences of Central Bank lending to government.

…both the Central Bank’s inability to issue coins and runaway domestic prices are rewards for the poor choices made by the markets. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our currency has been debased by and inflation is rampant because of the Central Bank’s unwillingness and/or inability to aim for and maintain stable prices.

Why then do we continue to ignore policy errors, while blaming our people’s love for holding cash? In truth, a comprehensive reform of our currency would have been a more fact-based response by the Central Bank to our current challenges. “Equivalent to about 30 cents, ought the N200 denomination to be a note or a coin?”, was how a friend who until recently taught Economics put this problem. As a coin, the N200 would better bear the vicissitudes of both rapid circulation and poor handling. But have our people not indicated large-scale indifference to coins?

Put differently, has coinage not been implicated in the debasement of our currency? On this reading, both the Central Bank’s inability to issue coins and runaway domestic prices are rewards for the poor choices made by the markets. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our currency has been debased by and inflation is rampant because of the Central Bank’s unwillingness and/or inability to aim for and maintain stable prices.

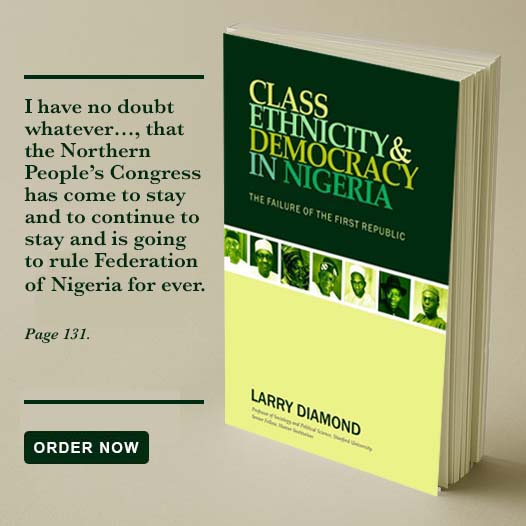

Also Read: Think Nigerian Democracy is Expensive? Try Autocracy

How to remedy this failing is the challenge that the next Federal Government faces if it is to improve our monetary policy outcomes.