Defying World Bank Predictions, Migrants Sending More Money Home but Remittances to Nigeria falls to 2008 Level

Remittances to Pakistan has risen by 9.4%. Pakistanis working abroad could not perform Hajj due to the new coronavirus pandemic; they have sent some of the Hajj-related expenses back home.

In the wake of the decline in economic output set in motion all over the world by the new coronavirus pandemic, the World Bank predicted back in April 2020 that remittances to low and middle-income countries would decline by 20% this year. This was expected. Immigrants in countries like the United States, one of the major sources of remittances, were disproportionately affected by the job losses that followed the outbreak. With diminished or vanished income, it would be difficult to send enough money back home.

The economic impact of the shrinking of remittances was anticipated to be devastating—remittances accounted for three times the amount of government aid received by developing countries in 2019. Countries like Tajikistan rely heavily on remittances, as they make up 33% of GDP. However, despite the World Bank’s worst fears, remittances appear to remain strong. In fact, migrants have sent more money to some countries.

Thriving amidst a Pandemic

Countries like Mexico have been spared of the economic doom forecasted by the international financial institution. In the first eight months of 2020, Mexico recorded $26.4 billion in remittances, a 9.4% increase from the same period in 2019. Pakistan hit an economic milestone in July when it recorded $2.768 billion in monthly remittances, an all-time high for the South Asian republic. The Philippines’ remittances hit $3.09 billion in July 2020, a 7.6% year-on-year growth. Bangladesh’s inflow of remittance grew 50% year-on-year in the July-August period. Egypt’s remittances saw a 9.4% year-on-year spike in July.

Also Read: BIG READ: Immigration & History: Where Remittances Come From

Why the Spike in Remittances?

Remittances remaining steady at all during a pandemic is curious, let alone when rising to record numbers. Mexico is a perfect example of this contradiction. In March, the World Health Organization officially declared the pandemic, and Mexico’s remittances hit a record $4 billion. Banco de México struggled to find rational explanation for it, as the development defied logic given the observable circumstances.

Initially offering weak theories such as money-laundering by drug cartels [improbable since the remittances were multiple transactions involving small sums] and the possibility that Mexican immigrants kept their jobs due to working in “essential services” [the data does not support this], Jonathan Heath [Vice President of the Banco de México] resorted to the only convincing arguments analysts have put forward: that Mexicans in the United States perhaps benefited from a federal unemployment package and were then motivated to send much more money than usual back home. This is especially probable considering their families back in Mexico were most likely out of work and struggling more to make ends meet. The immigrants took it upon themselves to ease their families’ pain by doubling or tripling their remittances even as they struggle to stay above water in their host countries.

Interestingly, Pakistan’s good fortune was not despite the pandemic, but because of it. With a major share of the remittances coming from Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates—two countries with significant Muslim populations—the cancellation of hajj pilgrimage this year meant that Pakistanis who would have gone on hajj sent more money back home. Also, Pakistani immigrants abroad tend to return home in July to celebrate Eid Al-Adha. The travel restrictions meant they had to stay back abroad and possibly send home extra money that would have been spent on flight tickets according to Muzzamil Aslam, a senior economist.

The Filipino immigrants were able to send so much money back home for mostly two reasons. The easing of lockdowns in source-countries meant Filipinos who had been out of work could get back to earning an income, and perhaps overcompensate for the slowdown in income by sending more money than usual. Another factor that contributed to this development was the coincidental weakening of the dollar in terms of exchange rate, which then inflated the value of remittances sent home.

Despite the World Bank predicting Bangladesh would suffer a 22% plunge in remittances this year, the rising inflow of remittances took the country’s reserves to $38.48 billion. The Bangladeshi government has taken credit for this success. Finance Minister AHM Mustafa Kamal says this is all owed to the 2% cash incentive on remittances, which encouraged foreign-based Bangladeshis to send money to the country and get an addition 2% added to their money by the government.

One common factor for the rise in remittances is the altruism of foreign-based citizens sending money back home. Many immigrants prioritize their families even at their own detriment. As seen in the cases of Mexico, Pakistan and the Philippines, immigrants tend to forego a lot of personal comfort to ensure the safety of those back home, especially during these trying times.

Another factor is the access to stimulus packages or other forms of unemployment benefits available to immigrants who have lost their jobs. With these, they are able to send money back to their friends and families despite not having a steady income. In fact, some were inspired to send home even more money now, considering that their families back in their home countries probably do not have access to the same stimulus checks to aid them survive the pandemic.

It is also important to note that a lot of immigrants are considering going back home due to the pressures of the pandemic and growing anti-foreigner sentiment all over the world. About 300,00 Filipinos are expected to return to their country this year. In order to ensure a comfortable adjustment to life after their return, they could possibly be sending money back home to their families to help them set up necessities like housing that would help them settle in easily. That would explain the sudden inflow of money.

Also Read: IMF Says Nigeria’s Economic Growth to Decline by 4.3% in 2020.

However, these cases do not form a complete picture. The global sum of remittances could still fall despite the fact that some countries are receiving more money from their citizens living abroad. Some countries are experiencing a fall in remittances that is perfectly in line with the World Bank’s predictions.

The Unlucky Ones

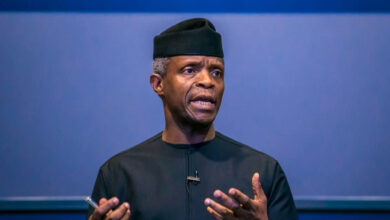

Some countries have not been so fortunate, and Nigeria is one of them. Nigeria succumbed to the effects of the coronavirus in terms of remittance inflows. The second quarter of 2020 saw remittance inflows drop to the lowest since 2008. This is a major blow to Africa’s most populous country and Sub-Saharan Africa’s top destination of remittances.

For El Salvador, remittances have been described as a lifeline that keeps people out of poverty and makes up 21% of the country’s GDP. In such a poor country that has little to offer its citizens, many of the young population are outside the country earning a living to provide for their parents and siblings back home. The country received $5.6 billion in remittances last year, far more than the $724 million it received in foreign investments. Sadly, it could not avoid the consequences of the pandemic. It witnessed an 8% drop from H1 2019 to H1 2020.

The fluctuating nature of remittances makes it difficult to predict the patterns of trends; it remains to be seen just what global remittance will be by the end of the year.