“There is also the argument that watching the exchange rate matters because we are import-dependent. That is obviously untrue as the import of goods (physical) and services (Invisibles) is only 19.8% of GDP in Nigeria, much lower than 27.8% for Sub-Saharan Africa as of 2019”.

Why do we obsess over the exchange rate to the neglect of more important issues like Nigeria’s high and rising inflation?

One man is responsible: the governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, Godwin Emefiele. He has managed to suck us into an obsession over the exchange rate by creating more confusion than clarity.

Why does the exchange attract so much attention?

Since 2014, the Nigerian economy has endured two major FX crises. Only two (2018 & 2019) of the last seven years have been without FX crises. For the other five years, there were critical FX issues such as the lack of dollar liquidity, violent devaluations, and a wide exchange rate premium in the parallel market segment.

Because the fate of the naira is strongly tied to oil exports, a weakness in either or both oil prices and production has the sudden implication of reducing FX supply. This then causes the naira’s struggles. But this is not a death sentence and should not persist for long if appropriate measures are taken. The main challenge over the past seven years is that Emefiele’s measures are inadequate and untimely. Consequently, naira’s struggles are never short-lived.

The CBN actively tries to fix exchange rates, which was the case when the Bank regularly intervened in the FX markets to maintain a fixed rate of N360/$ between 2017 and 2019. When oil prices started to fall in late 2018, the CBN drew down its reserves to maintain that rate rather than devalue the Naira. This made the Bank unprepared to fight a crisis like COVID-19 because its firepower – external reserves – had weakened due to inappropriate policies during the years of boom.

Yet having weak reserves is only a part of the problem. The appropriate policy with the emergence of COVID-19 should have been 1) a quick and appropriate exchange rate adjustment and 2) proper communication of policies to calm the public. With these measures, people and businesses can move on to other things.

However, the CBN fails at doing what is appropriate, so all the attention is on the exchange rate. It is hard for people and businesses to move on when the parallel market is moving wildly and trading at a significant premium (N485/$ vs $410/$). It is harder to move on when the CBN wants them to sell their dollars at the official rate, which means lower value for money. It is impossible to move on when access to dollars is limited and not available when it is most needed.

Nigeria’s inflation problem is among the worst in Africa

The obsession with the exchange rate is a big distraction because prices of everyday items have been increasing at a rapid pace. As long as you live in Nigeria and have most of your obligations in the country, watching the inflation rate matters more than the exchange rate. What many people do not also understand is that the high inflation rate is a major reason why the naira is losing value. If the value of money is determined by what it can buy and inflation reduces what money can buy, obviously the currency of a country with high inflation will tend to lose value faster than that of low inflation countries.

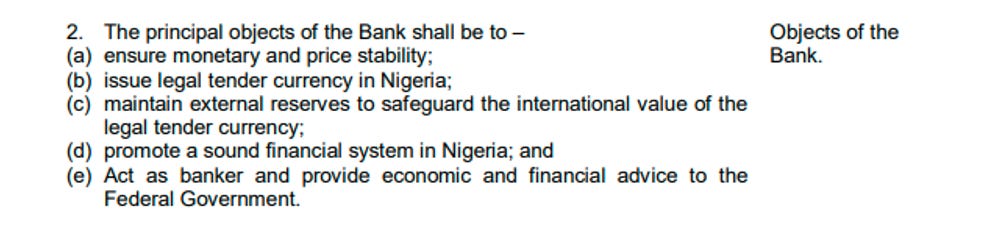

The CBN’s most important job is to ensure stable prices and low inflation. The Bank’s official inflation target is in the range of 6.0% – 9.0%. A paper published by Central Bank staff in 2018 supports this target. If inflation exceeds that level, it starts to have a negative impact on the economy. Recently, the CBN tends to reference 12.0% as the dangerous limit not to cross, but one of the papers suggesting this level is less recent (published in 2013).

The last time the official target was met was in 2014 when inflation was 8.0% (average for the year). Between 2016 and 2020, the average annual inflation was 13.7%. What this means is that average prices would double every 5.4 years in Nigeria. Using data from 45 Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), I found that 36 countries performed better, with only Sierra Leone, Liberia, DRC, Angola, Eritrea, South Sudan, Zimbabwe and Mali doing worse. We can agree that Nigeria is in company of countries that are not held up as good examples on important matters.

More recently, inflation has increased from a low of 11.0% in August 2019 to 17.3% in February 2021. This has been driven by food inflation which rose from 13.2% to 21.8% over the same period. The trend in food inflation is devastating because the share of consumer expenditure that is spent on food is around 56.7%. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) which is used to calculate inflation does not fully reflect this, with food being only 50.7% of the index. Regardless, food actually accounted for 58.3% of the index value in February 2021.

This is not the way to run an economy. Low and stable inflation is essential for macroeconomic stability, growth, employment, and investment.

Also Read Food Inflation: Why “Tomato is f**king expensive”

What is responsible for Nigeria’s high and rising inflation rate?

There are two main popular theories on what is responsible for inflation. The first is what economists call demand-pull: the view that too much spending can cause inflation if production is weak in the economy. This is why people say inflation is too much money chasing few goods.

One of the major factors driving demand-pull inflation is money supply, which is basically cash and other short-term assets that can quickly be converted to cash. To control this type of inflation, you have to watch money supply very closely. This is how Central Banks all over the world fight inflation.

The second school of thought is cost-push inflation – the view that the high cost of production (wages, raw materials, etc) is passed on to consumers. There is little Central Banks can do about this as their tools (interest rate, CRR, OMO, etc) mainly control only the amount of money in the economy.

What does the CBN believe? The Bank aligns more with cost-push inflation with a twist. They say what is responsible are structural supply-side (what affects businesses/production) issues such as insecurity, weather challenges, and transport and distribution infrastructure. This basically means that the government is responsible for fixing these and bringing down inflation.

Considering that these factors affect food supply and food prices strongly influence inflation, there is merit to this. But while it is true that these structural issues contribute to high consumer prices, the CBN is not as powerless as they want people to believe.

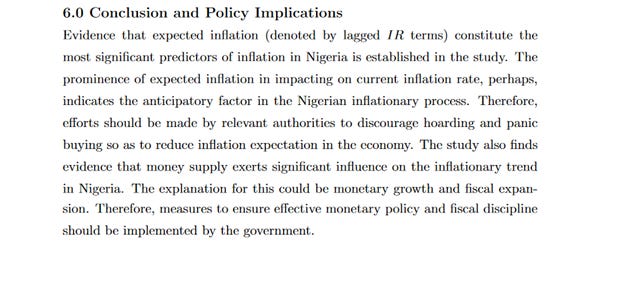

The presence of structural issues does not mean that inflation is also not driven by what the CBN can control – money supply and expected inflation, among others. There is a lot of economic papers authored by CBN staff showing that money supply is one of the determinants of inflation in Nigeria but I consider this recent 2018 study.

They also mentioned that expected inflation contributes to inflation in Nigeria. The importance of expected inflation is explained by the fact that if people expect prices to continue to rise, they will factor this in their economic and financial decisions. For instance, expected inflation will influence how businesses think about costs and in turn pricing for their products.

The truth is not one single factor is responsible for inflation. It is a mixture of different things that the CBN can control (money supply/expected inflation) and what the government should focus on (structural factors). However, rather than create policies to control inflation, the CBN is contributing to pushing it up.

Outdated policy approach to fighting inflation

Even though we have established that money supply and expected inflation are important, CBN does not tackle inflation through both. They announce money supply targets but they are not as diligent in keeping to them. I will cover this later but let’s start with what they feel strongly about.

What the CBN prefers is using the exchange rate as the main tool to fight inflation because we import consumer goods. This is outdated. It is also one of the reasons for the CBN’s obsession with a strong and fixed exchange rate.

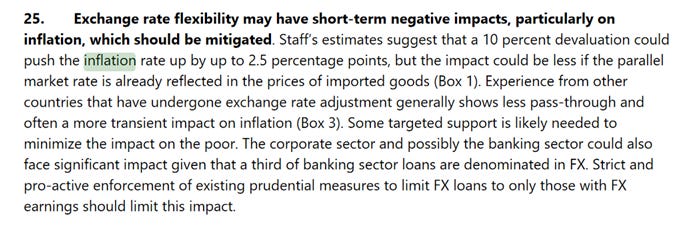

It is true that exchange rate movements affect prices. However, the pass-through of exchange rate depreciation to inflation is not 1 to 1: a 10% devaluation does not equal an increase in consumer prices by 10%. The IMF confirms that the relationship is actually around a 2.5% increase in inflation for a 10% devaluation and that this increase is temporary. Remember Egypt?

The impact of devaluation on food prices, the primary driver of inflation, is also limited. In fact, imported food is only 13.3% of the CPI basket.

There is also the argument that watching the exchange rate matters because we are import-dependent. That is obviously untrue as the import of goods (physical) and services (invisibles) is only 19.8% of GDP in Nigeria, much lower than 27.8% for Sub-Saharan Africa as of 2019.

Beyond the exchange rate, the CBN also tries to control inflation by setting targets for monetary aggregates. Monetary aggregates refer to indicators of money supply such as M1, M2, and M3 – these combinations show the level of cash, deposits, and near-money (short-term assets with high liquidity) in the financial system.

This monetary targeting approach follows from economic theory that money supply growth affects inflation (I have discussed this earlier). However, modern central banks have left this behind, with inflation-targeting now preferred – this helps Central Banks to manage inflation expectations, which I earlier mentioned is a significant factor driving inflation in Nigeria. When Soludo made a briefing on the “Strategic Agenda for the Naira” in August 2007 (almost 14 years ago), he mentioned a transition to inflation targeting by 2009.

The US discontinued monetary targeting twenty years ago. This is because economists have discovered that the relationship between money supply growth and inflation has weakened, so targeting money supply growth cannot be effective as the primary tool. There is a paper published by the Central Bank of Nigeria confirming this but also stating that this does not mean money supply growth is not a driver of inflation.

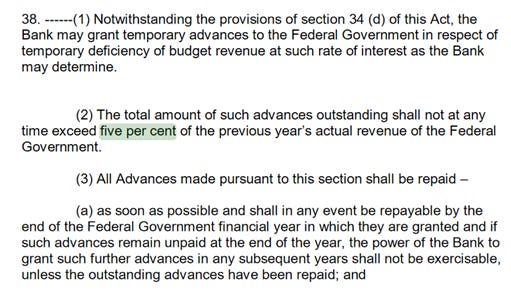

CBN’s unconstitutional lending to the FG

Another challenge is the CBN’s financing of fiscal deficit beyond what is allowed by the constitution. What is permitted is 5.0% of prior year’s revenue which must be repaid within the same year. Between 2015 and 2020, the total lending to the FG was N11.0tn when it should have not been more than N491.3bn. Between 2019 and 2020, it was N6.1tn when it should have not been more than N230.8bn. Failure to repay this borrowing as and when due should mean lack of access to more funds but the CBN has kept funding the FG.

The CBN is giving the FG too much free money to spend. Normally, when the FG needs to borrow, it does this in the debt market from investors. Because the cost of the debt is tied to market rates, they cannot borrow recklessly. However, with the CBN deciding to lend the FGN money continuously (without cost or considerably low cost), it can become reckless, with harsh repercussions if it continues for an extended time.

This is why many countries try to ensure that Central Banks are independent as fiscal authorities might want to use them to pursue their agenda. This was the case in Germany in the 1920s (printed money to pay reparations for war) and recently in Zimbabwe and Venezuela.

Also Read: High Food Prices Push Nigeria’s Inflation Up 13.22 per cent

The CBN’s dangerous adventures on the supply side

The Bank can do much more to fight inflation, but has decided to focus on things outside its scope and for which it lacks the capacity to execute.

The CBN has become a big part of the supply side. Because inflation is driven by food and we must contain food prices, the CBN has been doing a lot when it comes to food.

The Bank gives loans to farmers to support them so that we can produce more food and bring down prices. These loans are often poorly targeted and not exactly fit for purpose. It could work if the loans were used for the intended purpose but some farmers use it to marry more wives and never repay. But why is the CBN giving loans to farmers when it says that structural factors are responsible for inflation? Will the loans automatically fix bad transport/distribution networks, insecurity and weather challenges?

Still on food and supporting farmers. The CBN banned about 44 items(fertiliser, maize and milk have been added) from being qualified for official FX for imports because they believe we have the capacity to produce them locally. This is untrue because local producers cannot meet demand and the prices are too high anyway. Obviously, these items are still imported but with expensive FX sourced in the parallel markets, which translate to higher prices for consumers. It is clear that the CBN is responsible for the higher inflation that accompanies the policy.

Also, the CBN strongly supported the closure of borders, which also drove prices higher. In a situation where food is very expensive locally and unavailable, but cheap globally, imports can be used to ease the pressure on consumers. When imports are restricted, value is transferred from the majority of Nigerians to a few producers who are very inefficient. It does not make sense that the CBN is creating and supporting policies that will push up inflation. A better approach will be using food imports to support consumers while we try to fix our structural issues. The tariff on a lot of food items is very high, which we could reduce to get lower food prices if we fear that food imports will also be affected by devaluation (like I said earlier, this connection is weak).

What the CBN should be doing

The CBN is always quick to mention that its tools are inadequate to fight inflation. However, the Bank chooses weak tools which are poorly used. The Bank’s money supply targets often miss the mark. Using the exchange rate to fight inflation also creates unintended consequences that destroy the economy.

The policies are also inconsistent. For instance, if the CBN has a target of 6.0% -9.0% and believes that inflation beyond 12.0% will affect growth, why is it reducing interest rate to support growth when inflation is 17.3%? The correct choice should be to tighten interest rates.

Erdogan and Emefiele seem to be rewriting economics by thinking that lower interest rates will fight inflation. What is important is to set inflation targets, communicate it and use tools that will best help with effective transmission of monetary policies. If the Bank does not know how to achieve this, they should invest in upgrading their capacity.

The CBN should also stop going beyond its mandate and reduce its excesses. Giving loans to farmers will not solve structural issues. Restricting the importation of goods and supporting a devastating anti-trade stance will also not boost food supply and reduce food prices.

To summarise, the CBN’s policies contribute more to pushing up inflation than bringing it down. the CBN’s policies contribute more to pushing up inflation than bringing it down. But it must return quickly to policies that will help contain inflation so that people and the economy can be stronger.

Adebayo Bakare is the Chief Operating Officer of Money Africa

One Response

Have you an article on the ‘Gbatueyos’ in Ministry of Works & Housing? If yes, please republish or send to me asap.