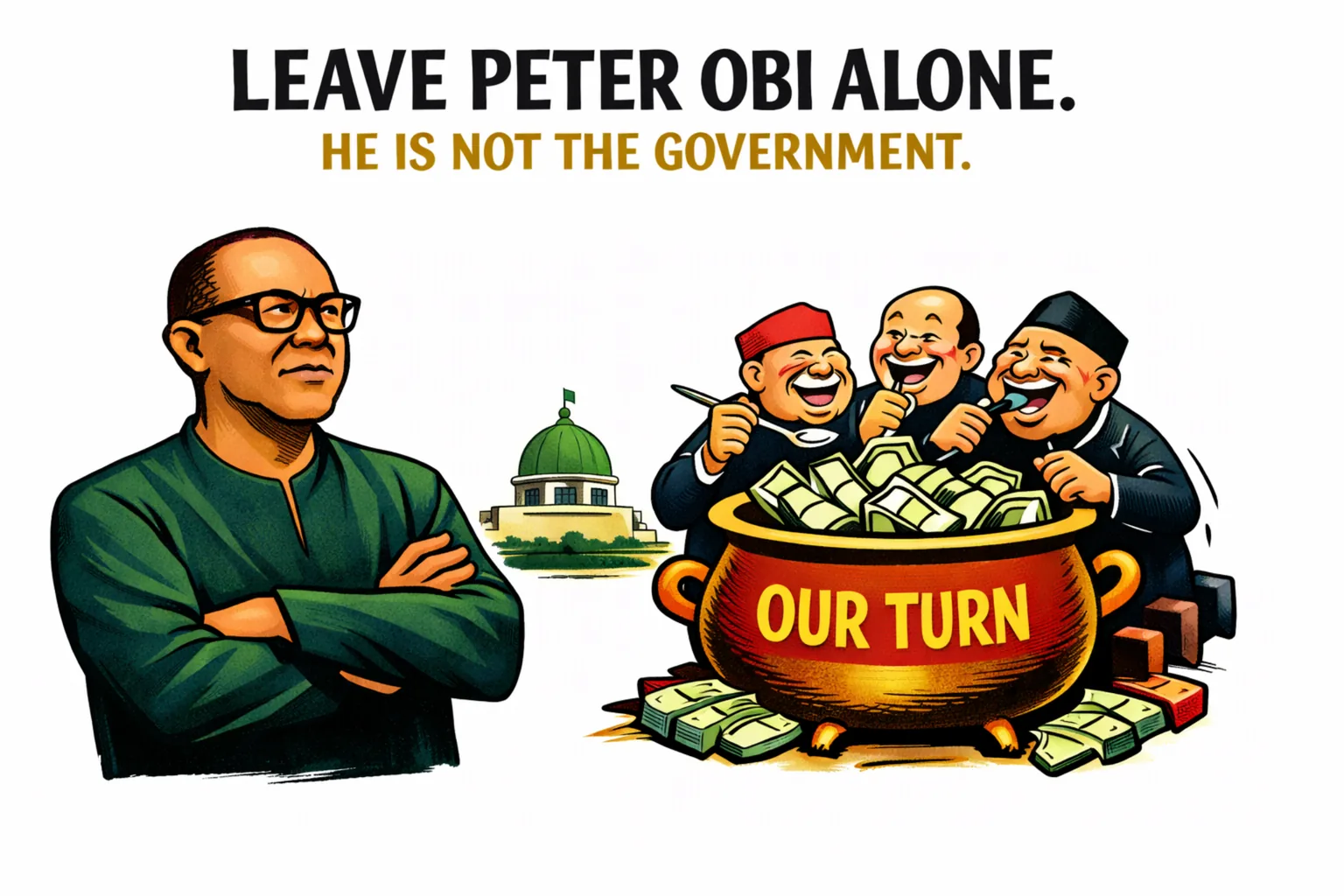

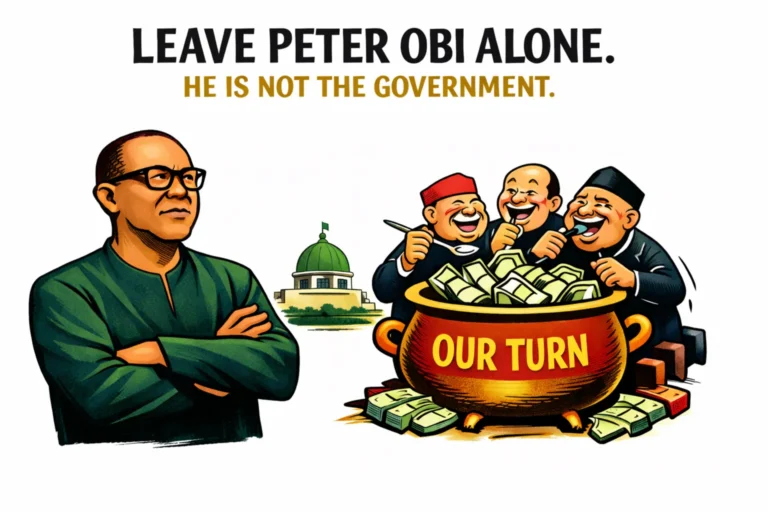

“Leave Peter Obi alone. He is not the government.” The phrase has become a reflexive defence among the supporters of Peter Obi, the Labour Party’s presidential candidate in the 2023 elections and by far Nigeria’s most popular opposition politician, whenever questions are raised about the effectiveness of Nigeria’s opposition. It is also a revealing one. Embedded in it is a narrow understanding of the role and potential of political opposition parties in a democracy—and why their quality matters more than their mere participation in, or victory at, elections.

The problem is not Peter Obi as an individual. It is a political culture that elevates opposition politicians into symbolic saviours while exempting them from the scrutiny, accountability, and performance benchmarks expected of anyone seeking to govern.

Opposition Leaders Are Not Activists

Opposition to government comes in many forms. Journalists expose abuses. Labour unions mobilise workers. Activists and social-media influencers apply moral and political pressure. These groups demand accountability, protect rights, and amplify public anger. They play essential roles in a democracy. But an opposition political party occupies a fundamentally different position.

Unlike activists or commentators, an opposition party is a government-in-waiting. Its central obligation is not merely to criticise the incumbent but to demonstrate superior ideas for governing society. It must invest heavily in policy knowledge, institutional understanding, and execution capacity—because it ultimately seeks to rule.

An opposition leader, unlike a journalist or activist, should never be limited to articulating governance failures; he or she should possess the will and resources to develop policy and institutional solutions to those failures. Those solutions must be rigorous and viable because the opposition politician, unlike the activist, is preparing to enter government to implement them. They are a test of the extent to which an opposition politician is ready for office and a preview of expected performance.

Supporters of Peter Obi—and of Nigeria’s opposition more broadly—are often surprised, even offended, by the suggestion that an opposition leader can be criticised for unpreparedness or ineffectiveness. In their view, only those currently wielding power deserve scrutiny. That view misunderstands how good government is produced.

A competent opposition improves governance even when it is out of power. When it develops credible solutions and forces them into public debate, governments may anticipate or even adopt those ideas, regardless of who gets the credit. This “policy theft” by an incumbent is a welfare gain: citizens benefit even as the ruling party attempts to disguise or minimise the borrowing, and the opposition tries to expose it. The more the opposition demonstrates superior ideas for governing society and improving people’s lives, the stronger its case for replacing the government at the ballot box.

Nigeria’s deeper problem is that what passes for political opposition parties does not operate at this level. The opposition’s knowledge of economic, social, and security challenges—and its ideas for solving them—are often no better than those of the average citizen who suffers from and criticises government failures.

Activism Is Not a Substitute for Governing Ideas

Civil society groups, unions, and activists often lack both the incentives and the technical capacity to propose workable alternatives to complex structural problems. They criticise symptoms while defending the structures that produce them. Crucially, they do not expect to implement, or be held accountable for, the policies they advocate.

This distinction is not theoretical. In 2012, when the Jonathan administration attempted to remove fuel subsidies, a broad coalition of opposition politicians, labour unions, and activists resisted. The resistance was not grounded in a superior reform design but in populist rejection. The outcome was not social protection but the continued enrichment of rent-seekers, particularly within the petroleum sector. Some of those opposition figures later entered government.

Over time, the politics of fuel subsidy produced an absurd and tragic result: Nigeria borrowing externally to fund subsidies while hosting the largest population of out-of-school children in the world. For four decades, variants of this coalition—activists, unions, and opportunistic politicians—have helped entrench ruinous policies. What has changed is only the scale of the damage.

The Problem with Mega Parties

Equally damaging is the nature of Nigeria’s opposition parties themselves. Rather than building policy depth, they focus on assembling mega parties—inter-ethnic coalitions of familiar political actors recycled since 1960. The opposition thus invests heavily in competing for power but little in developing ideas or policies capable of improving citizens’ lives.

Politics becomes turn-by-turn: access to power rotates, rents are redistributed, and citizens are repeatedly mobilised with moral outrage rather than governing ideas. This pattern ran from the APC’s rise in 2014 through its years in power. It now threatens to repeat itself with new alignments seeking their own turn in 2027.

Civic Duty Is Not Enough

Another retort against criticism of the weakness and unseriousness of Nigerian opposition politics is: “You don’t need the opposition to put pressure on government; it is a civic duty.” This sounds principled but misses the point. Civic responsibility does not end with voting, and citizens must indeed hold those in power to account. But without a policy-serious opposition party, accountability remains shallow and episodic.

Politics becomes organised primarily around winning power, and political parties take turns entering Aso Rock with little or no preparation for the business of governance. Activism cannot substitute for organised, technically competent alternatives to government. Governments often fail before they even enter Aso Rock. Once in office, the intellectual bandwidth needed to design policy solutions and refine governing ideas is quickly overwhelmed by the day-to-day politics of retaining power.

Why We Should Never Leave Him Alone

So when supporters say, “Leave Peter Obi alone; he is not the government,” they are inadvertently conceding the argument. They are admitting that they do not expect the opposition to shape policy today, improve governance now, or prepare rigorously for governing tomorrow.

What Nigeria actually needs is not untouchable opposition figures or ever-larger coalitions of recycled politicians. It needs small, disciplined opposition parties that relentlessly develop solutions to national problems—and just as relentlessly mobilise citizens around those solutions.

Such parties may not win power immediately. But they would do far more to improve governance and citizens’ welfare than the familiar ritual of mega political coalitions composed largely of politicians waiting for “our turn” to eat. Nigerian politicians will continue to assemble these mega “culinary” parties for as long as opposition figures are shielded from scrutiny rather than judged by the seriousness of their ideas.

Peter Obi’s performance as an opposition leader attracts criticism precisely because many of his critics see in him the potential to disrupt this pattern. He is treated as someone capable of redefining Nigerian politics—from a pursuit of power to a contest over what to do with power. Former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, by contrast, is rarely the focus of such scrutiny because he is generally perceived as operating within the existing political logic rather than challenging it.