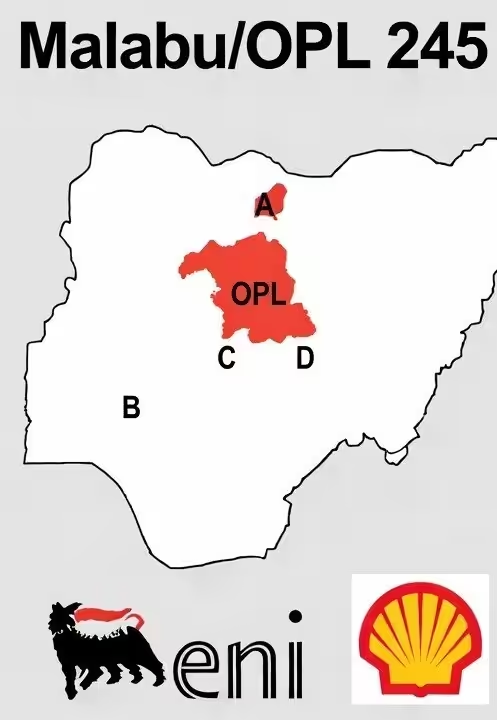

Senegal’s withdrawal of Oranto’s Cayar Offshore Shallow (COS) licence is not just a company story; it is a regulatory statement about parked acreage. Nigeria has the same problem at scale: licence holders who win blocks, sit on them, and then treat the asset as an option to be traded — while national production, reserves replacement, and fiscal receipts suffer.

Senegal’s Hard Line — and Why It Matters

Senegal’s Ministry of Energy and Petroleum withdrew Oranto’s COS rights in September 2025 after repeated demands for bank guarantees tied to the work programme were not met. In regulatory terms, the message was simple and deliberate: a petroleum licence is a conditional right, not a perpetual option.

Crucially, Senegal treated the failure to post financial guarantees as a substantive breach, not a paperwork lapse. The guarantees were framed as proof of capacity to fund seismic work, appraisal, and drilling — without which acreage becomes stranded and the state bears the opportunity cost.

This approach aligns Senegal with a growing group of regulators moving away from permissive acreage-holding and toward performance-based licence retention.

Nigeria’s “Drill or Drop” Policy and Its Implementation

Nigeria’s upstream regulator, the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), under Chief Executive Engineer Gbenga Komolafe, has articulated a “Drill or Drop” policy to tackle the problem of dormant acreage. Under this policy, operators are expected either to begin meaningful drilling /development within stipulated timelines or to relinquish their licences. This policy is designed to ensure the optimal use of petroleum assets and prevent dormant blocks from tying up potential reserves.

According to NUPRC statements, the “Drill or Drop” approach:

-

prescribes that unexplored acreage be relinquished if operators fail to execute work programmes, and

-

is part of the Commission’s broader strategy under the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) 2021 to revitalise Nigeria’s oil sector and attract new investment.

At industry meetings, Komolafe emphasised that companies must begin production or development within set timeframes or risk losing their licences, aligning regulatory expectations with international best practice.

Actual Enforcement: When Policy Meets Action

Beyond policy statements, the NUPRC has taken concrete enforcement actions under the PIA’s powers:

-

In September 2025, the Commission revoked the operating licence of the Oritsemeyin Rig after determining that operational failures during drilling contributed to multiple non-productive hours and a forced sidetrack of the UDIBE-2 wellbore. The revocation came after formal notices were issued and compliance timelines were allowed to elapse, illustrating that the regulator can and does sanction operators under statutory powers when conditions are not met.

This shows that the regulator is willing to exercise its legal rights — not just talk about them — though these enforcement instances have so far been limited relative to the total number of non-performing licences.

Nigeria’s Deeper Problem: Licences That Never Turn Into Barrels

Nigeria’s challenge is not unique, but it is unusually persistent. Across marginal fields, shallow offshore blocks, and even some onshore assets, licences have been awarded to firms that lacked the capital, technical depth, or balance-sheet credibility to develop them.

The result is a familiar pattern:

-

acreage held for years with minimal activity;

-

timelines repeatedly extended;

-

farm-ins pursued as exits rather than development partnerships;

-

production and reserves growth underperforming potential.

While the NUPRC has occasionally acted — most visibly with the Oritsemeyin revocation and the policy statements on dormant oil licences — the harder cases are those where payments are made but work is not done. These cases are precisely what Senegal’s COS decision now throws into sharp relief.

Where Regulators Have Taken Back Licences for Non-Development: Clear Precedents

Ghana: Work-Programme Discipline

Ghana’s Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act, 2016 (Act 919) embeds strict work-programme and relinquishment provisions. Licence holders who fail to execute agreed exploration activities have seen acreage automatically revert to the state at the end of licence phases, pushing operators to either drill or exit early.

United Kingdom: Use-It-or-Lose-It Policy

The UK’s North Sea Transition Authority enforces firm work commitments. Licences can be terminated or partially relinquished when operators fail to proceed with required wells or development milestones, and under-developed acreage is re-offered in subsequent rounds.

Uganda, Kenya, Angola

These African jurisdictions have embedded relinquishment and termination provisions in their regulatory frameworks, and states have reclaimed acreage when work programmes lag. Uganda insists on adherence to field development plans; Kenya uses a formal “show cause” process before termination; Angola’s post-2019 reforms shortened exploration windows and clarified relinquishment rules.

These examples show the legal logic behind licence withdrawal is consistent worldwide:

-

failure to execute the minimum work programme;

-

failure to demonstrate financial capacity (including guarantees);

-

breach of licence conditions or timelines;

-

non-payment of fiscal obligations.

Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Act contains these powers explicitly. The issue is not whether the law allows revocation, but how consistently regulators apply it.

Why Senegal’s Move Should Unsettle Nigeria’s Upstream Status Quo

Senegal’s COS decision sends a message that resonates far beyond Dakar: access to acreage is no longer a substitute for the capacity to develop it.

For Nigeria, where idle licences have quietly become an accepted feature of the upstream landscape, the implications are uncomfortable but unavoidable:

-

capital markets discount Nigerian assets when development timelines are uncertain;

-

serious operators hesitate to farm-in where enforcement is weak;

-

the state loses years of production and revenue while acreage sits dormant.

If Nigeria is serious about reversing production decline and restoring upstream credibility, the path is clear: licences must belong to those who can drill, not merely those who can acquire.

Senegal has now demonstrated that this principle can be enforced. The question is whether Nigeria is prepared to do the same — not just in policy rhetoric, but in consistent regulatory action.