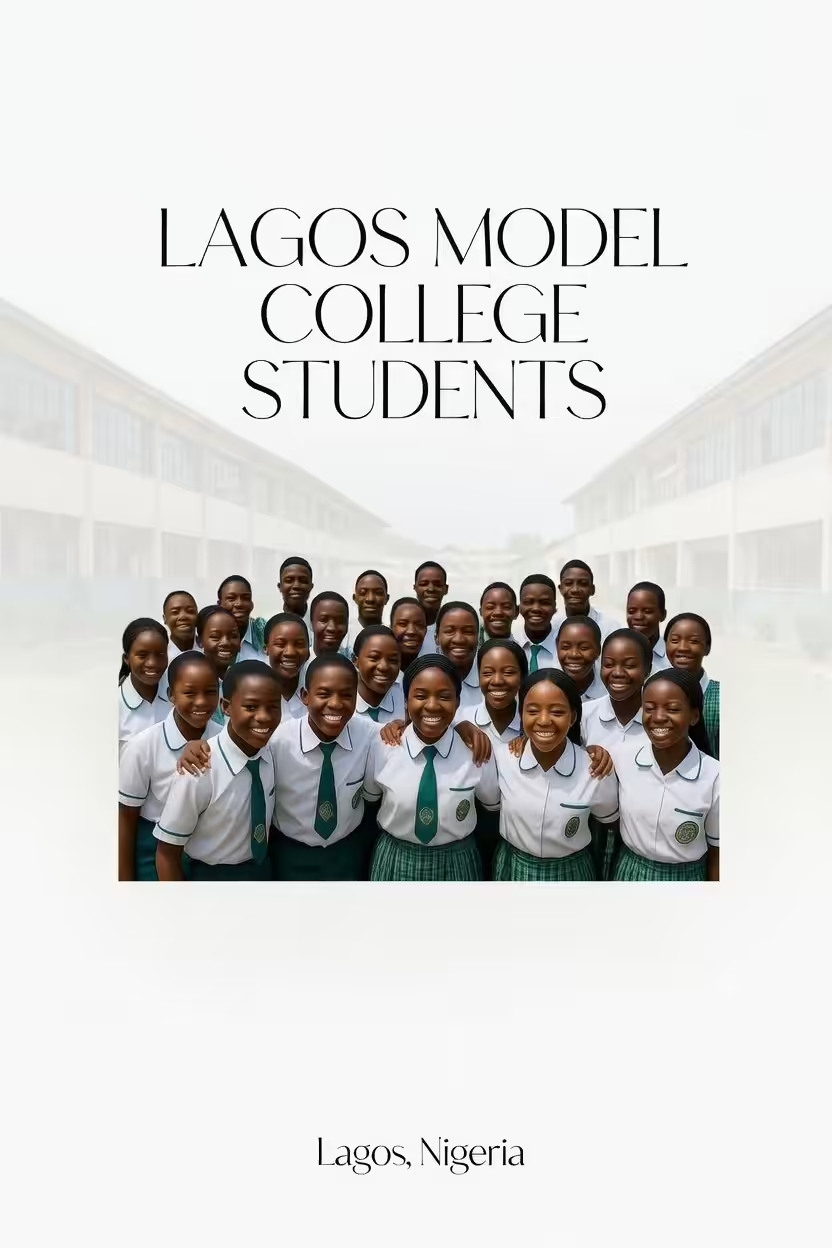

When 280,941 children completed primary school in Ondo State in 2015, only 44,504 enrolled in JSS 1 the following year. That is a transition rate of just 15 per cent. Across Nigeria, the journey from primary six to junior secondary school has long been marked by dramatic losses, with millions of children falling through the cracks at this critical juncture.

EduIntel’s Sofiyat Raimi reviewed available data from 2015 to 2021 and her review paints a sobering picture of educational access across the country, even as it shows modest improvements in some regions. Her analysis compares the number of children in the final year of primary education in 2015 with pupils in the first year of junior secondary in 2016, as reported in UBEC education statistics digests. The same methodology was applied to primary six data from 2019 and 2020, comparing these with first-year junior secondary figures for 2020 and 2021, respectively.

While the figures are now several years old, they nonetheless tell a story that remains relevant for Nigerian families and policymakers alike. The patterns they reveal continue to shape the lives of young people today, and more recent data from education authorities would be invaluable in understanding whether these trends have shifted. New education statistics from UBEC are expected this year.

Also Read:

- Working Lives: The Petrol Attendant Who Sponsors His Own Education at Yaba Tech

- Lower Education and Trust Levels Barriers to Women’s Financial Inclusion – CBN Study

- Working Lives: The Primary School Teacher Who Has Not Been Promoted in 12 Years

- Free School Meals: Indonesia to Boost Incomes and Economic Growth with $28 Bn School Meal Plan

The national transition rate stood at 60 per cent in 2015, improving to 74 per cent by 2020. This means that for every 100 children who completed primary school in 2015, only 60 made it to secondary school the following year. By 2020, that figure had risen to 74, representing real progress but still leaving more than a quarter of primary school leavers dropping out of the formal education system.

Regional disparities are massive. In 2015-2016, states like Kwara and Lagos recorded transition rates of 143 per cent and 150 per cent respectively. Meanwhile, Kogi managed just 15 per cent, Ondo 15 per cent, and Yobe 25 per cent.

These variations cannot be explained by poverty alone. They reflect deeper structural issues around school availability, cultural attitudes towards education, and the particular challenges faced by communities affected by insecurity.

There are of course progress worth noting. For example, Cross River’s transition rate jumped from 46 per cent in 2015 to 167 per cent in 2019, before settling at 165 per cent in 2020. Bayelsa moved from 94 per cent to 138 per cent, while Rivers went from 80 per cent to 174 per cent. These dramatic increases suggest significant policy interventions, but they can also be as a result of changes in data collection methods that warrant closer examination.

In the northeast, Borno presents us with a bit of good news. Despite grappling with years of insurgency, the state has seen its transition rate improve from 53 per cent in 2019 to 93 per cent by 2021. This represents remarkable progress under extraordinarily difficult circumstances, though the state still needs to grow its primary enrolment in a bid to reduce the out-of-school population.

I don’t want to overwhelm you with figures, but behind the statistics are individual children being left behind. The 615,134 children who left primary six in 2020 across Nigeria but did not show up in junior secondary school in 2021 have had their basic education truncated. Knowing the quality of learning taking place in primary schools across the country, it is likely that these children, many of whom are now entering adulthood, might be condemned to a life of illiteracy and limited economic opportunity.

The data itself raises important questions about the quality of education data in Nigeria. Government agencies collecting data need to provide explanations where seemingly implausible figures are recorded. How do we account for transition rates exceeding 150 per cent? Even though we can speculate as to the reasons for transition rates exceeding 100%, official analysis of the data could have provided more credible explanations.

More fundamentally, we need current data. Education planning without recent, reliable statistics is like navigation without maps. State and federal authorities must prioritise data collection and make it publicly accessible. UBEC has not published school census data online since 2022, and this is deeply unfortunate.

Finally, we must confront the economic pressures that pull children out of school. For many families, a child’s labour or early marriage represents immediate financial relief. Without social protection programmes that reduce the cost of education and provide support to vulnerable families, transition rates will remain stubbornly low in the poorest communities. Where support is available but children are still out-of-school or dropping out, government should bring out its stick and enforce its own compulsory education rules.

The question I want to leave you with is whether Nigeria will marshal the resources and political and policy commitment needed to ensure that every child who completes primary school can continue their education, or we will end up creating another generation of uneducated or poorly education youth?

Sodiq Alabi writes regularly for Arbiterz and leads programmes at EduIntel.