A Nigerian living in New York, who works as a senior development specialist at the United Nations, reacted with disbelief when news broke that armed protesters had overrun the new Museum of West African Art in Benin City. “This is an international embarrassment. I am canceling my planned trip with the familly to Benin during the holidays. In personal protest at the madness. This madness must stop,” she told Arbiterz. Her frustration echoed a wave of shock across diplomatic, cultural and philanthropic circles, where MOWAA — a $25-million, architect-designed museum complex intended to be West Africa’s most significant cultural institution in decades — had been hailed as a turning point in the continent’s cultural renaissance.

The disruption on Sunday, which forced the cancellation of MOWAA’s opening week and sent foreign visitors fleeing, marked a dramatic escalation in a simmering dispute over cultural authority, restitution politics and power dynamics in Edo State. Far from a routine protest, the attack struck at the heart of an institution created to transform how African heritage is conserved, studied and displayed — and to do so at a scale unmatched anywhere else in Nigeria or the region. As Daniel Wilbert, a finance expert who has worked across continents, put it, “It’s just a complete shame… no words to capture the mindset of those rallying against this.”

An Institution Designed to Reclaim African Narratives

The Museum of West African Art was conceived to serve not merely as a gallery, but as a research and conservation powerhouse aimed at reclaiming narrative authority over African history. Its origins lie in Edo State’s heritage-focused urban renewal agenda but quickly evolved into an independent, professionally governed non-profit. The independence allowed MOWAA to pursue global partnerships and funding insulated from Nigeria’s turbulent political cycles.

Prominent figures including Phillip Ihenacho, Ore Disu, and artist Victor Ehikhamenor led the development, working with international partners such as the British Museum, MARKK Museum Hamburg, the Benin Dialogue Group, and research teams from Oxford and Cambridge. Governance is anchored by a board that includes Dr Myma Belo-Osagie, Dr Andreas Görgen, and Eric Idiahi, supported by an international development board chaired by Ebele Okobi.

Built on a Scale West Africa Has Never Seen

Designed by Ghanaian-British architect Sir David Adjaye, the 15-acre campus is among the most ambitious cultural projects in modern African history — a blend of rammed-earth architectural forms inspired by Benin’s palace complexes and cutting-edge global museum standards. Facilities include a 48,000-square-foot conservation and archaeology institute, the Rainforest Gallery, a digital heritage lab, an artisans’ hall, and an artist guesthouse, making it the only institution in West Africa capable of hosting international-standard exhibitions, storing restituted artefacts, and training conservation scientists under one roof.

International support has been strong. Beyond core donor contributions, the German government, Ford Foundation, Open Society Foundations, and the Mellon Foundation — which made a $3-million grant in 2024 — have publicly aligned themselves with the project.

“It represents years of effort to tell our stories with dignity and rigour,” said Kayode Adegbola, lawyer and art dealer. “Let’s protect the spaces that protect our culture. Dialogue, not disruption, should lead the way.”

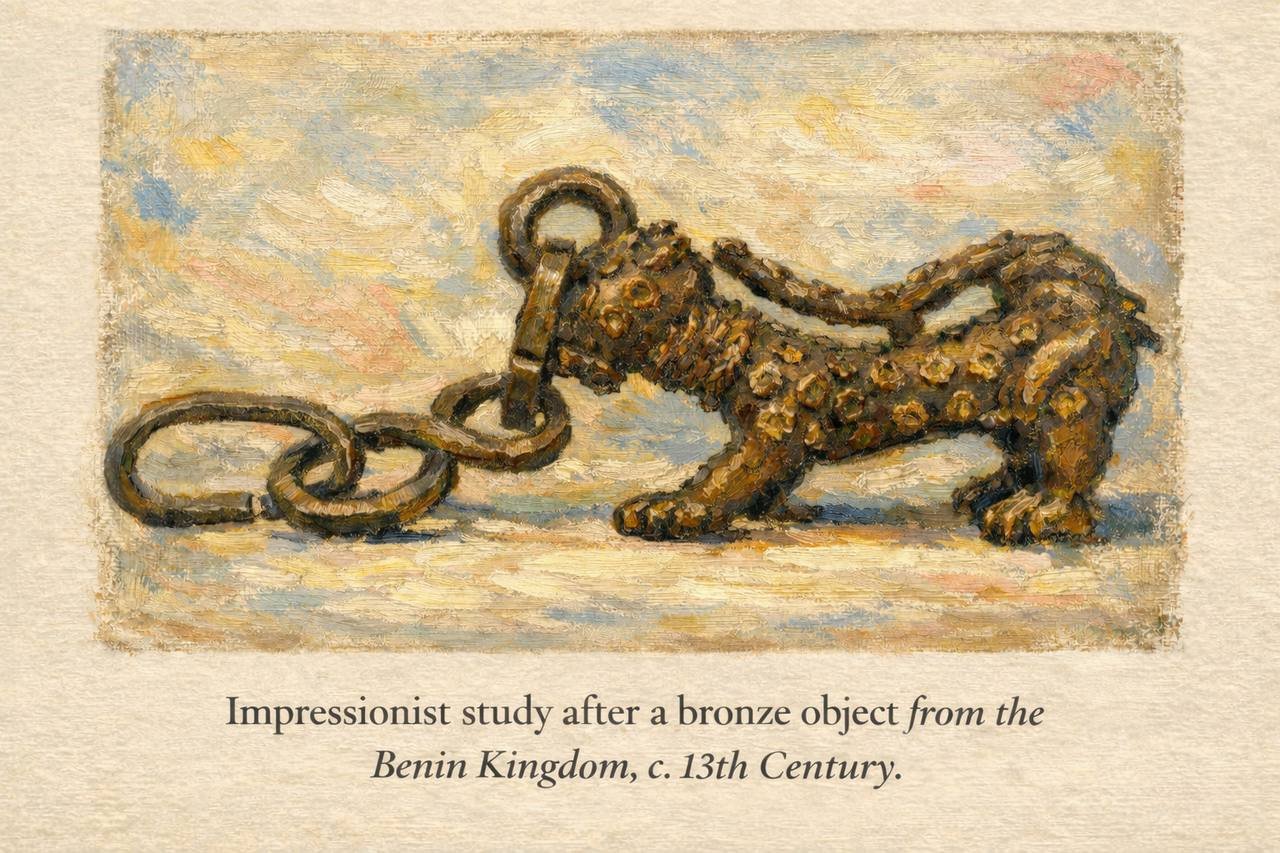

The Cultural Reckoning and a Century-Old Dispute

Sunday’s attack stemmed from longstanding tensions over who should control the returning Benin Bronzes — the Oba of Benin, the federal government, or an independent institution like MOWAA. Protesters referenced former President Muhammadu Buhari’s 2022 statement handing ownership of repatriated artefacts to the Oba, even though MOWAA is not the repository for restituted objects.

“What was meant to be a proud pre-opening celebration,” wrote Wiebe Boer, Ph.D., “descended into violence over conflicts of ownership and legacy. This is deeply unfortunate… and risks becoming yet another reason foreign countries may delay or refuse the return of Nigerian cultural artefacts.” Drawing a sharp comparison, he added: “Egypt recently inaugurated its massive new museum without such internal turmoil — a reminder of how politics and cultural divisions pull Nigeria three steps back just after we’ve struggled to move two steps forward.”

He also expressed personal concern for MOWAA Director Phillip Ihenacho, “who has poured immense time, personal credibility, and resources into this project.”

“Too sad and deeply shameful,” Moji Ogundiran., a project management specialist based in the Netherlands, commented.

The Political Backdrop

The Political Background

The MOWAA crisis is unfolding against the backdrop of a widening political rift between former Governor Godwin Obaseki and his successor, Governor Monday Okpebholo, who come from starkly different political traditions and governing styles. Obaseki, a former investment banker widely regarded as a technocrat, built his administration around modernisation, institutional reforms and high-profile projects funded through global networks in finance, art and philanthropy. His international connections — from Wall Street to global foundations — enabled him to conceptualise and attract support for ventures such as the Museum of West African Art (MOWAA), the Benin River Port and his sweeping digital reforms in education.

Okpebholo, by contrast, is viewed by many analysts as a more conventional Nigerian politician — grassroots-oriented, patronage-driven and eager to assert political control over state institutions. Since assuming office, he has moved quickly to undo or review several Obaseki-era initiatives. He has halted parts of the education reforms, ordered audits of last-minute land allocations, replaced key technocrats linked to Obaseki, and reopened politically sensitive files from the previous administration. The revocation of MOWAA’s Certificate of Occupancy fits into what many see as a broader effort to dismantle Obaseki’s legacy piece by piece.

In the revocation order dated October 21, 2025, Okpebholo cancelled the statutory right of occupancy granted to the Edo Museum of West African Art Trust (EMOWAA) Ltd/GTE, invoking “overriding public interest” under Sections 28 and 38 of the Land Use Act. He argued that the 6.21-hectare property, once the site of the Central Hospital, should revert to its original purpose. The timing — coinciding with the museum’s pre-opening events and the arrival of foreign donors — raised eyebrows among cultural and diplomatic observers.

The political temperature climbed further when Okpebholo held a high-profile meeting with the Oba of Benin, signalling alignment with palace interests, particularly in the contentious debate over who should control restituted Benin artefacts. While there is no evidence that he met the EU Ambassador specifically about MOWAA, the diplomat and several international partners have separately expressed concern about the instability surrounding the project.

For Edo people, whose per capita income remains among the lower tiers in southern Nigeria, big-ticket cultural projects like MOWAA — with its potential to attract international tourists and elevate Nigeria’s global cultural standing — may not appear to solve immediate bread-and-butter issues. This disconnect partly explains why the outrage over the disruption of the opening, allegedly by hired thugs, has come mainly from highly educated, widely travelled Nigerians who see MOWAA as a rare opportunity to boost the country’s global profile and reshape how Nigerian heritage is represented abroad. To them, the attack was not just a local disturbance but a national embarrassment that undermines years of work to restore international confidence in Nigeria’s ability to manage its cultural treasures.

Caught in this crossfire of politics, class expectations and cultural identity, MOWAA now stands at the centre of a bitter struggle between Obaseki’s technocratic legacy and Okpebholo’s more traditional political approach — with the fate of Nigeria’s most ambitious cultural project hanging in the balance.

The Federal Government Scrambles to Contain Fallout

Nigeria’s Minister of Art, Culture and the Creative Economy, Hannatu Musa Musawa, said the matter is receiving “attention at the highest levels of government,” warning that the assault “threatens the environment necessary for cultural exchange and the preservation of our artistic patrimony.”

Federal officials are now engaging state authorities, security agencies and cultural bodies to prevent further unrest.

Concerns Over Further Repatriation of Nigerian Artefacts

The confrontation at MOWAA has triggered alarm among international cultural partners, many of whom worry that the violence could jeopardise future returns of Nigerian artefacts. Museum officials, restitution advocates and global financiers say the scenes in Benin City may reinforce long-held fears within foreign institutions that Nigeria lacks a stable, unified framework for receiving and safeguarding restituted heritage. As one European curator privately noted, the unrest “risks resetting years of progress.”

These concerns come at a sensitive time: several museums across Europe and the United States are weighing additional transfers of Benin Bronzes and other looted works. Sunday’s disruption, they warn, could harden institutional caution, erode donor confidence and revive arguments for keeping contested artefacts abroad.

A banker from Edo State who travels to Benin City frequently told Arbiterz: “They haven’t done the work to properly conceive or build the Benin Royal Museum they keep talking about. What they really want is to take over the MOWAA building, rename it the Benin Royal Museum and forget all the legal frameworks behind MOWAA’s establishment. It’s essentially an attempt to seize the project by force. I only just realised how blatant it is. How do we expect anyone to take Nigeria seriously — even from an investment perspective — if a traditional ruler, backed by a Governor, can promote and insist on this level of chaos?”

His frustration reflects the growing intrigue and distrust that the battle over the control of the repatriated artefacts has generated. While some Nigerians insist that the Oba of Benin should be the rightful custodian — since the bronzes were looted from the palace in 1897 — others argue that a modern, professionally run institution like MOWAA offers a more credible, internationally acceptable framework for conservation, training and long-term stewardship.

The stakes for Nigeria are enormous. MOWAA was intended to be the anchor of Edo State’s cultural revival and a symbol of Nigeria’s readiness to manage world-class collections. Instead, the museum now sits closed — not as a sanctuary for West African heritage, but as the flashpoint of a deeper struggle over who should control, interpret and protect the nation’s most historic treasures.

.