[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Our value proposition is twofold. Jamborow creates a digital identity and financial (transactions) profile for millions of unbanked citizens in the informal sector and also services the formal financial services providers by providing a link to a vast number of people in the informal sector, saving them the cost of marketing and the cost of acquisition.”

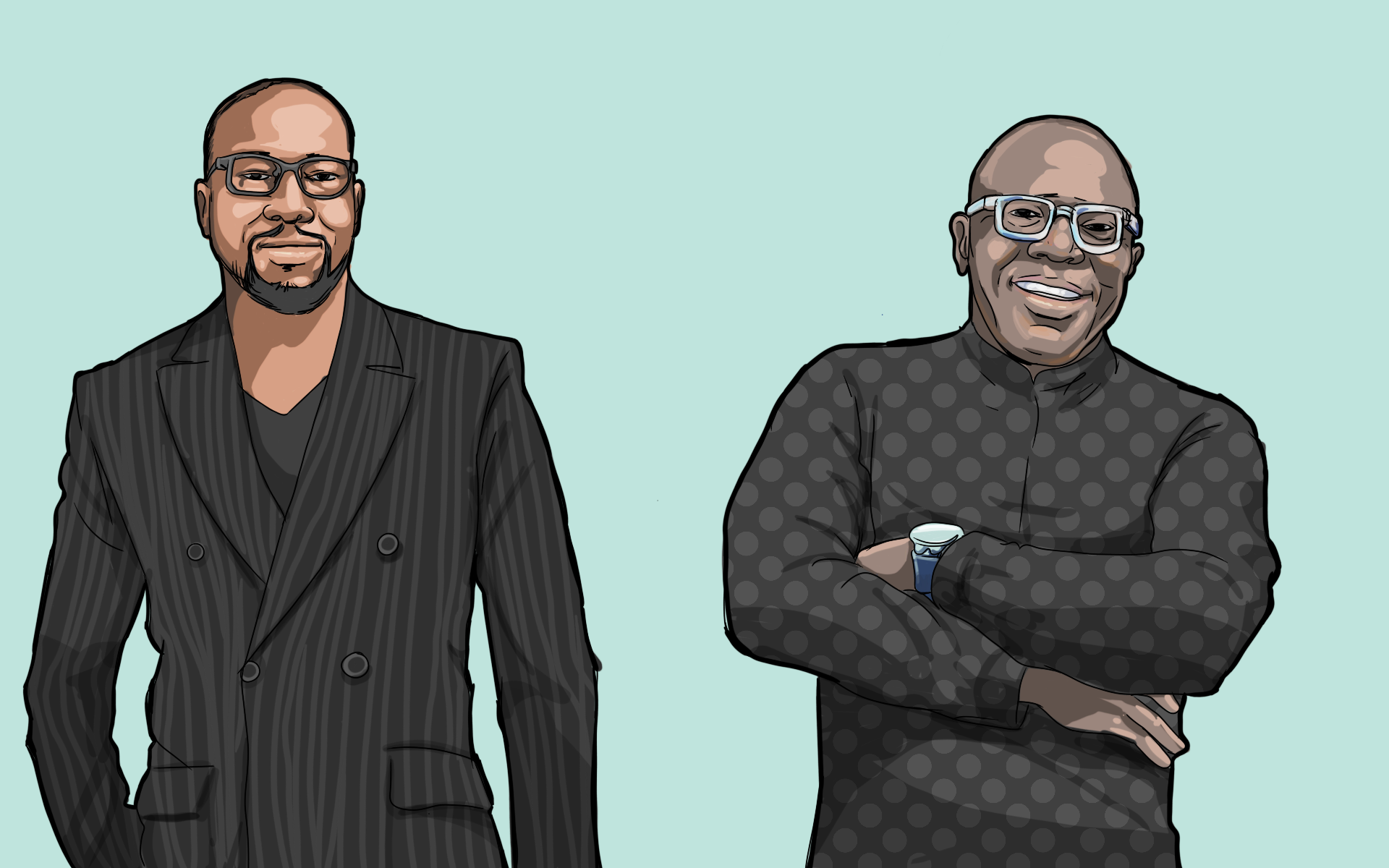

Arbiterz spoke to Moses Onitilo (CTO) and Olusegun George (CEO), co-founders of the fintech, Jamborow. Jamborow collects membership records of often-market-based savings and loans associations (popularly known as ajo or esusu) together with individual members’ records of saving, borrowing and repayment in the associations. The information is stored on Jamborow, constituting ready and robust KYC and credit rating data that enables formal institutions such as banks, insurance companies and foundations etc. to lend, sell products or give grants to millions of informal sector traders and artisans through the platform. Jamborow has used technology to create a marketplace where millions of artisans, market men and women, hawkers etc. have the credentials (“whitelisted” according to the founders of Jamborow) to access credit and other financial services and products such as insurance and affordable housing. It is currently operating in seven African countries and starting operations in another seven countries by the end of 2021.

How was Jamborow created?

Also Read:

- FCMB Partners Jamborrow To Drive Financial Inclusion in Farming Communities

- Haskè Ventures invests $150, 000 in ProXalys, Tech Provider for Informal Traders

- Olu Akanmu: "Over 30 Million Nigerians Have Digital Identity But No Financial Accounts”

- Piggyvest 2024 Savings Report: Low Savings Threaten Nigeria’s Economic Growth

We have known each other since we were 11. We both attended High School and both left Nigeria to study business and finance at Southwest London College, which is now South Bank University. Segun stayed on at South Bank for graduate studies while I moved on to Middlesex University to study Computer Science and Maths. He went into investment banking while I went into information technology. But at some point, everyone pivots back home. So Segun returned to help the establishment of UBA Capital and became the COO while I also started to visit Nigeria regularly. He had worked with Goldman Sachs in London. We started talking about something transformational that we could do together leveraging our skills and experiences in finance and technology. We could think of giving back on an Africa-wide scale because both of us have worked extensively in over 20 different markets on the continent.

From the onset, we were clear we wanted to do something that would significantly contribute to alleviating poverty in Africa. We were looking for ways to make people in the grassroots more involved not only in the formal sector finance but also the formal sector economy. So we regard the task or opportunity as beyond Financial Inclusion. We started thinking of something that could tie the mass of economic actors at the grassroots level together. It was easy for us to see that economic activities at the grassroots in Africa have a similar ecosystem – market women, orange sellers, matatus, bikes, etc. We have traveled and worked all over Africa and have seen the same things everywhere. But we still devoted two years to doing research in Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Uganda, etc. It was during this time that the name Jamborow occurred to us. It’s a combination of the colloquial “jam”, to run into someone and borrow. It expresses the vision of our business to be a platform where businesses could safely and confidently connect with millions of Africans in the informal sector and lend them funds and where these people after we have helped transform them into formal entities, could also easily buy valuable services like an insurance for their business and families. We were incorporated in 2018. Our headquarters is in the United Kingdom, a convenient place from which to drive the business into African markets. We are also incorporated in Nigeria and Kenya.

So Jamborow enables people to lend to each other?

Not at all. Jamborow is a B2B platform. We are not lenders of any sort. We don’t practice lending or take any credit risk whatsoever. What we mean by peer-to-peer lending on our platform is two licensed institutions jamming one another on the platform and providing credit or facilitating services to one another at the institutional rather than personal level. The way it works is that we deal with microfinance banks, savings groups, savings associations, and cooperatives. In East Africa, they have an acronym for cooperatives – SACCO – which stands for savings and cooperative groups. These savings groups have the same structures and functions all over Africa. It is called ajo by Yoruba in Nigeria and in the East of the country, esusu. Funny enough they are called susu in Francophone Africa and other parts of Africa. They do the same things as savings and credit unions. So those are our clients. That’s where you get demographics if you want to do financial and economic inclusion at a massive scale. The fact that they don’t have bank accounts does not mean that they don’t conduct financial transactions. They conduct financial services but they do it in their own manner and have an ecosystem that has lasted for centuries. Esusu and ajo are how Africans saved and banked before the western banking system arrived on the continent.

Please, can you talk more about the formal businesses that you enable to provide financial and other services to (the members of) savings and credit unions?

Basically, what we have done is modernise traditional groups. We have automated and digitised their records. The savings and records of the ajo and esusu groups are out of the banking system. Jamborow acts as a conduit for members of these savings groups to access diverse services in the formal sector based on their membership and records. The service providers are insurance companies, microfinance banks, commercial banks, cooperative banks, NGOs, Healthcare providers, etc. All these services are somehow related. So if a member of an ajo group needs to pay for medical care and doesn’t have the money, he or she can come on Jamborow to borrow money. He or she would also be connected to a Healthcare practitioner or provider that would provide the healthcare service required based on the agreements that we have in place. Jamborow eliminates the paperwork. The service will be based on the smart contracts on our platform. The service provider will also use the KYC information that is already digitised on our platform. The artificial intelligence element of Jamborow also matches users with goods and services as well as loans based on a credit score that is derived from their membership of an ajo-like group and their history of borrowing and repaying in the group. Jamborow is almost like a supermarket. We are a marketplace for the formal sector to sell services to the informal sector. We connect the dots.

But one has to be a member of a savings or credit association to access loans or services?

Yes. You cannot just go off the street and download the Jamborow app. You will find it in PlayStore and IOS but it is not going to work because you have to be a member of a licenced savings group, as ajo, esusu or susu group or a cooperative to use Jamborow to access loans or services. We onboard these groups then their members can access services. We sign an agreement with them and so they provide the data, KYC information of their members. Once that is done, their members can see and access all the financial services and products on Jamborow. These ajo or esusu groups keep very good records. We provide the technology and platform that formalise and authenticate the data. We essentially provide a white label so their members can access services and products based on their records.

So which is the bigger market – the traders and other small businesses saving and borrowing with microfinance banks or the informal savings and credit groups you are bringing into the formal financial sphere?

The savings groups are bigger. The microfinance banks have not been able to service that demographic because they also operate as commercial banks and their interest rates are high. The savings groups are regulated in a place like Kenya so we have the numbers that show us how big they are. SASRA (Societies Regulatory Authority), the regulatory body in Kenya, has about 3300 savings groups under it. Some of the savings groups have more than 4,000 members.

What’s the advantage of regulating these savings and credit groups as you have in Kenya?

Savings groups have to be registered and licensed. They pay membership dues to SASRA, which then lends the pooled membership dues to the smaller savings or credit groups. It pays a dividend on the membership dues to the groups it regulates. We don’t have this structure in Nigeria but there is no difference in terms of our relationship with these ajo, susu or esusu groups. The woman selling coconut or fruits in Nairobi or Lagos saves every month with an ajo group and has a credit footprint with the group which is invisible to banks or other formal sector businesses. She thus can’t borrow from the formal sector financial institutions. They have no data on her. So whether in Nigeria or Kenya, what Jamborow does is to make available good quality data on the millions of people who generate huge incomes and transactions in the informal visible to formal sector financial institutions and other companies. We have solid data on what goes on in the ecosystem of informal markets. We have data on how much people save. We know when they borrowed, how much, what they used the funds for, and when they repaid. Formal sector institutions come on Jamborow to plug and play. For instance, a microfinance bank can come on Jamborow and grow its customers from 2,000 to 10,000. Without any need for KYC or any kind of additional paperwork as we have deep historic data on the potential customers. A Nigerian institution can decide to lend to members of a Kenya susu.

Please, can you talk a bit more about the value add you bring?

Our value proposition is twofold. Jamborow creates a digital identity and financial (transactions) profile for millions of unbanked citizens in the informal sector. But we are also servicing the formal financial services providers by providing a link to a vast number of people in the informal sector saving them the cost of marketing and the cost of acquisition. The banks have not penetrated this vast segment of the economy where the majority of Africans belong. Even the large banks in Nigeria have about 18 million customers many of whom they share with other banks. So we provide access to the vast informal sector. And we have built a platform that requires only a simple phone that can process USSD technology to be visible on the Jamborow and access services. You don’t require a smartphone or the internet. Once we have taken your records from the ajo, esusu or susu group and have uploaded on Jamborow, you have all the credentials. You can access everything with a shortcode.

Is there any comparable technology in the market that allows people to enjoy fintech without smartphones?

You have to define what you mean by fintech. Fintech is very wide. You can compare Jamborow to the Ant Group of China which owns Alibaba. We are building a massive marketplace. Jamborow fits between FinTechs and TechFins; we provide the technology that serves financial services companies and new customers. A big upside for Jamborow is that we collect massive data on demography that there is little data on. We have been approached by the United Nations, the International Financial Corporation, and the World Bank who are all very interested in the kind of data we have been able to collect.

Also Read: Blended: Consumer Credit will Make Banks More Profitable – Yvonne Johnson, CEO Indicina

Which is the greater cost to you, your technology or the investment in establishing relationships with and amassing data from the informal savings and credit associations? It’s easy to assume collecting data is more expensive.

The cost of collecting data is negligible. People assume that the informal sector is not organised. That’s very erroneous. They are actually very well organised. They have solid, good processes in place. The ajo or susu groups all keep ledgers in which they record all the information. It costs us almost nothing to upload the information on our platform. It’s no cost to the savings and credit groups too. Once we load the data and everything is configured, we train the treasurer or group leader on how to use Jamborow and they train their members. It’s largely plug and play.

How do you gain their trust?

Through relationships. We never go directly to the people to sell. We do not sell. Someone once told us that he had never seen any marketing material from Jamborow. That’s because we don’t need to market the general public. We work by nurturing strategic partnerships. To earn trust, we go from the top down. We don’t go from the bottom up. In Kenya for instance, we went directly to the Cooperative Bank. Kenya’s Cooperative Bank is the 7th biggest cooperative in the world. They have over 22 million customers and 23,000 circle groups under them that they want us to serve. We adopted the same approach with the savings and credit unions in Kenya. We went to the SACO which regulates all the ajo-like groups in the country. Once we got the buy-in from these two institutions, we had access to thousands of the savings and credit and cooperative associations.

Kenya seems to be so far ahead in Fintech and Microfinance, is it your biggest market?

Potentially because of deeper mobile penetration and internet penetration on one hand and the other hand, they are way more advanced when it comes to the adoption of technology. They are the biggest case study in the world for mobile money today. Kenyans are ahead of the west or any other region of the world when it comes to mobile money. We stayed in Kenya for six months during the lockdown. We never used cash once to transact. We used our phones. We had to deliberately go to the ATM to withdraw cash so we could see what Kenyan currency looked like. Everyone uses the mobile money transfer service MPesa. All you need is a simple phone. Kenyans use MPesa to pay for everything – bicycle or taxi ride, fruits bought by the roadside. They transfer the payment via mobile phones within seconds. The Kenya mobile money technology is now being used by Danske Bank of Copenhagen. We consulted for Danske Bank on digital transformation for almost 6 months. We were working out of Copenhagen. Danske Bank now has six mobile money products which grew out of the bank investing in MPesa. It owns 25% of MPesa. It is now taking the technology developed in Kenya back to Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway. Danske Bank is the biggest bank in the Scandinavian. That is an indication of how advanced Kenyan fintech is. We are close to signing a partnership agreement with the Cooperative Bank of Kenya that will see members of 22,000 cooperative groups onboarded to access credit and products and services on Jamborow. The obvious attraction to the Cooperative Bank of Kenya is that they wouldn’t need to build a marketplace and the required technology.

So lenders such as microfinance banks can advance credit to members of these cooperatives?

It’s important to explain that the cooperatives are very small organisations, just a bit bigger than the esusu groups. A cooperative may have 27 members, formed on the basis of teaching in neighbouring rural schools. Most of the cooperative members don’t have bank accounts, they just use MPesa. But their associations have accounts with the Cooperative Bank of Kenya which is also (their) quasi-regulator. Jamborow is already integrating our API with the Cooperative Bank of Kenya’s IT system. So when we onboard a cooperative, each of the coop’s members will have a wallet on Jamborow that gives him or her access to products and services and that also stores data of their transactions. They immediately have a credit rating which can be improved in a few months. They can also leverage the presence on Jamborow to open a traditional bank account. So we are taking banking services to the unbanked in so many ways. But to answer the question directly, microfinance banks or other financial services groups won’t come on Jamborow to lend directly to individuals. They will lend to the cooperatives or esusu group that will then lend to their members.

So, there is no need for the lender to do any KYC?

No, the KYC, as well as the credit score, is already there for all members of cooperatives and esusu groups on Jamborow. It is derived from the historical record of each members profile.

Is this what you mean when you say Jamborow allows financial services firms to scale through automation?

Yes. We take away the cost of acquisition of new customers for microfinance banks and other kinds of financial services firms. Even the susu groups become more useful to their members because the members can access many services that help them grow their business on Jamborow apart from credit. So their membership too grows. Businesses that want new customers can send SMS blasts on Jamborow. The reach is greater than going out to recruit people physically.

Please, describe how the use of Artificial Intelligence works on Jamborow.

Ok. Take for example how healthcare insurance may find viable customers on Jamborow. If someone borrows N10,000:00 three or four times a year because they want to take kids to the hospital, the data processing flags that this is someone that needs and can afford health insurance which is cheaper and gives them peace of mind. He or she is borrowing money from an ajo or susu group but because the group is on Jamborow, we have all the data about the transaction. How much was borrowed and for what purpose. The data allows machine learning capabilities and helps the AI to do predictive analysis. It works well for everyone by making everyone make better decisions – whom to lend how much to, whom to offer what services, etc.

It’s almost like you are bringing KYC and credit scoring down to the village level. Apart from microfinance banks, what other kinds of lenders come on Jamborow to connect to customers?

We have commercial banks, healthcare companies, insurance, and nano insurance companies. We have foundations come on Jamborow to give grants to cooperatives or savings groups. An affordable housing company has signed a partnership with us to offer its products on our platform. It is now building houses for a Kenyan woman savings group. The women bought plots of land but they don’t have to use up all their savings in building the houses because they found affordable finance on Jamborow. We also have peer-to-peer lenders from the diaspora. The United Nations, International Finance Corporation, the World Bank and other non-profits and multilateral organisations are also talking to us. The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) is interested in us onboarding farmers so they could access remittances. The attraction is that the farmers would have ready KYC once we onboard them. Jamborow is like a shopping mall, the platform is there for all sorts of retailers to come in and sell – restaurants, clothing shops, etc.

Except that Jamborow already has the shoppers…

Exactly. We have the shoppers already. The retail companies are now offering them different things – shoes, bags, or food. All kinds of stuff. So, for companies selling services or products, coming on Jamborow is like a retailer renting a shop in a mall that is already full of shoppers waiting for their services or products.

Could you please explain more how peer-to-peer lending works on Jamborow?

An institution, for instance, a private company or even an individual may wish to lend money to a particular demographic on Jamborow, say small carpentry or interior decoration businesses or women traders doing high-volume quick turn-around wholesale trading. But they don’t have the license to lend money. The institution or individual will lend to the group through another institution on Jamborow that has the license to lend money. A foundation or NGO may have wanted to give a grant to a savings group that has qualified for the grant but may not have a way to monitor how the funds are being disbursed or what the recipients are using it for. When non-profits give cash grants to savings groups on Jamborow, they can monitor who is getting the money, what exactly they are using the money for, etc in real time. Someone can come on Jamborow and look for a savings group to lend $1,000 or $10,000 to through a licensed lending company, negotiating a favourable interest rate with them. We will onboard this individual as a peer-to-peer lender which means obtaining KYC information and doing a background check. This is to prevent money launderers and loan sharks. We are very cautious about compliance.

Are there lessons for Nigerian regulators in the way mobile money has taken off in Kenya?

First and foremost, we have to encourage the use of fintech platforms to which there has been some resistance from the formal drivers of the economy. This is why mobile money has not taken off in Nigeria. We have the biggest economy on the continent but don’t have mobile money despite a huge unbanked population. We estimate the population of the unbanked at the moment at 66% but I think it is closer to 86%. Other countries have rapidly reduced the number of unbanked citizens. Yes, we have tried things like agency banking but agency banking works well in an ecosystem in which fintech that they use as platforms for disbursement are thriving. People require digital wallets which actually remove the reliance or dependence on hard cash that agency banking still depends on today. When you talk to people with agency banking licences you realise that the concern for their own safety is an issue, which is hampering penetration. The widespread reliance on cash is why we don’t have petrol stations in Nigeria today that are open all night whereas in many African countries you have 24-hour petrol stations. It’s because of security risks. So yes, we do have a lot to learn. The regulators, the banks, the agent banks, the microfinance institutions, the co-ops, etc all have something to learn. But ultimately, it is regulators at the top that will allow mobile money operations to actually take off and service the economy the way they were designed to.

Please, could you name the seven countries Jamborow has full operations in now?

Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Mozambique, and Namibia. I don’t want to name the countries where we have agreements in place to operate but in which we are yet to roll out operations. We are about to start operations in Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Zambia but we have seven more countries where we have signed contracts.

Rolling out operations must involve a considerable expenditure on staff.

No. We use local partners. We have 13 developers spread between Nigeria and Kenya and our legal, marketing, and Head of Investor Relations also working out of Kenya. We do not have a large team. All these markets we are mentioning, we work there through local partners. We are fully on the ground in all the countries but we have offices only in Nigeria, Kenya, and London. We do a lot of work remotely. It helps because we have a very young team. Everyone is under 27. Our Head of Marketing is 26. Only the two founders and our Chief Technology Officer are 50.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_toggle title=”Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) — Jamborow”]

- When was Jamborow founded?

Jamborow was founded in 2018

- Who are the co-founders of Jamborow?

The co-founders of Jamborow are Moses Onitilo and Olusegun George, and they serve as CTO and CEO respectively.

- Who invested in Jamborow?

Jamborow is funded by Newchip.

- How much funding has Jamborow raised to date?

Jamborow has raised $400K.[/vc_toggle][/vc_column][/vc_row]