In a recent episode of The Morning Show on Arise News, Dr. Paul Alaje, Chief Economist at FPM Professionals, joined from Ibadan, Oyo State’s capital, to dissect the Nigerian government’s bold move to impose a 15% import duty on petrol (Premium Motor Spirit, or PMS) and diesel.

Broadcasting on November 10, 2025—the same day as this analysis—the discussion highlighted the policy’s multifaceted implications amid ongoing economic strains.

Dr. Alaje emphasized its varying impacts: revenue boost for the government, protection for local refineries like Dangote, added costs for importers, and potential price hikes for consumers, who could see petrol prices surge by N97–N150 per litre.

“This tax means something different to everyone,” he noted, underscoring how it could exacerbate inflation, particularly month-on-month, while small businesses—comprising over 90% of Nigeria’s economy—bear the brunt.

As Nigerians grapple with the aftershocks of the 2023 fuel subsidy removal, this tariff arrives at a pivotal moment. Proponents hail it as a safeguard for domestic production; critics decry it as a veiled subsidy for private refiners that could inflate living costs. .

The Announcement: A Strategic Pivot in October 2025

President Bola Tinubu approved the 15% ad valorem import tariff on refined petroleum products—specifically petrol and diesel—on October 30, 2025, as confirmed by multiple outlets.

The policy, detailed in a government memo circulated to key agencies like the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) and the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), applies to the Cost, Insurance, and Freight (CIF) value of imports. It mandates payments into a federal account, with verification required before discharge.

Originally proposed with a 30-day transition, Tinubu ordered immediate implementation to align with the “Renewed Hope Agenda,” aiming to curb cheap imports undercutting local refiners, stabilize prices, and enhance energy security.

The tariff is not purely revenue-focused but protective, officials insist, potentially saving forex amid Nigeria’s $30–40 billion annual fuel import bill pre-Dangote. However, with implementation slated for November 21, 2025, after a brief grace period, pump prices—currently hovering at N914–N940 per litre—could climb to N1,000 or more, adding nearly N1 trillion annually to consumer costs based on 50 million litres daily consumption.

Dr. Alaje, drawing from Punch reports, noted that even in October 2025—ten days into the month—Nigeria was still importing, questioning Dangote’s claims of sufficiency. This discrepancy fuels debates: Is the tariff premature protectionism or a necessary nudge toward self-reliance?

A Brief History: From Import Dependence to Dysfunctional Refineries

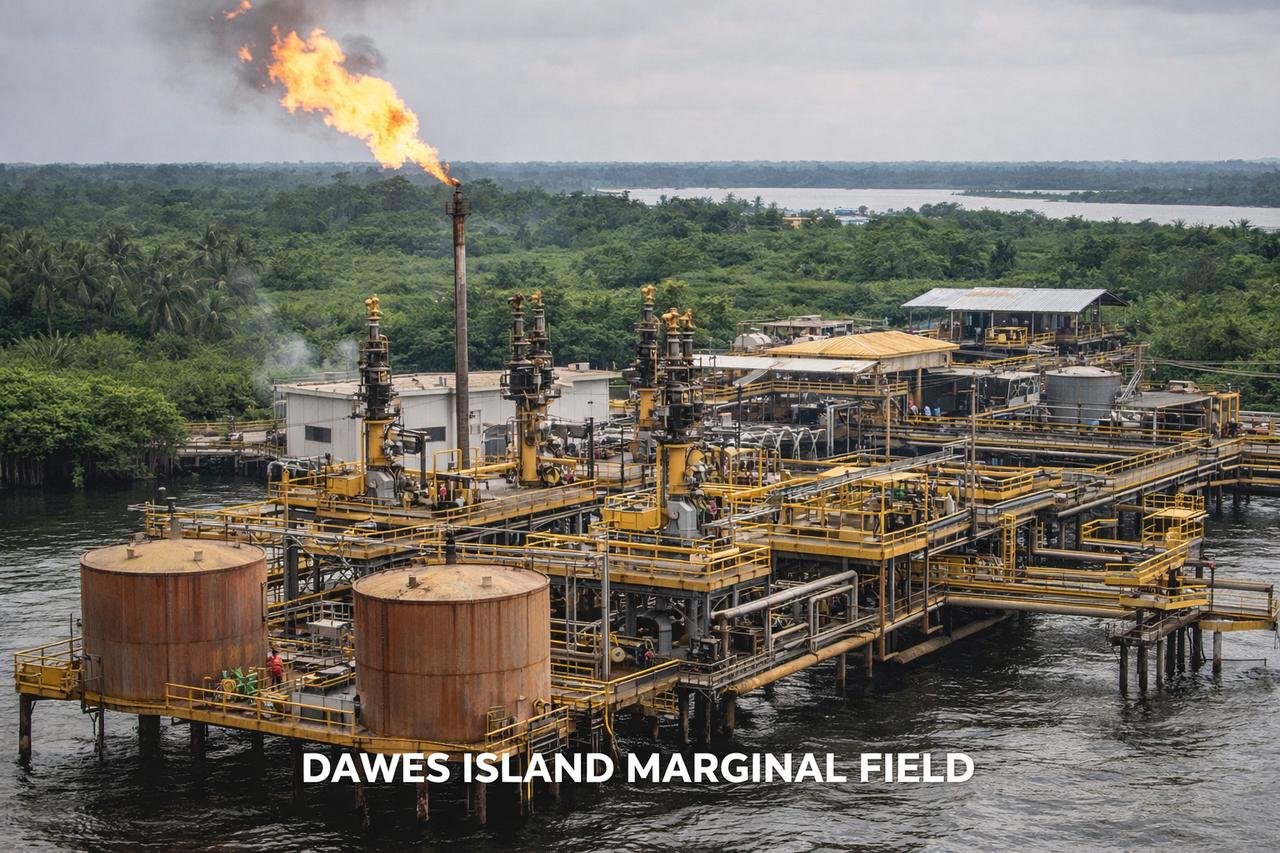

Nigeria’s fuel saga is a tale of squandered potential. Discovered in commercial quantities in 1956 at Oloibiri, Bayelsa State, oil became the nation’s economic lifeline by the 1970s, funding the construction of four state-owned refineries: Port Harcourt (1965, 210,000 bpd capacity), Warri (1978, 125,000 bpd), and Kaduna (1980, 110,000 bpd), with a second Port Harcourt plant added in 1989 (150,000 bpd).

Total installed capacity: 445,000 bpd, enough to meet domestic needs and export.

Yet, by the early 2000s, these facilities were ghosts—operating at under 10% capacity due to corruption, poor maintenance, and vandalism. Governments spent over $20 billion on failed “turnaround maintenance” contracts from 2001–2023, including $1.5 billion under Buhari in 2019, yielding minimal output.

Nigeria, Africa’s top oil producer (1.4–1.5 million bpd), imported 90–100% of its refined products, costing $18–$20 billion yearly and draining forex reserves. Smuggling to subsidy-subsidized neighbors like Benin Republic exacerbated losses, with estimates of 20–30% of imports diverted.

Enter the fuel subsidy regime: Introduced in the 1970s to shield consumers from global oil shocks, it ballooned to N4.39 trillion ($10.6 billion) in 2022—13% of GDP—benefiting elites and importers more than the masses. Subsidies kept pump prices artificially low (N185/litre pre-2023), encouraging overconsumption and waste.

Subsidy Removal: A Seismic Shift in 2023

On May 29, 2023, Tinubu’s inaugural address declared: “Subsidy is gone.” Prices tripled to N617/litre overnight, triggering nationwide protests and inflation spikes (from 22.4% in June 2023 to 34.2% by mid-2024).

Consumption plummeted: Pre-removal averages hit 64.14 million litres/day in Q1 2022, but post-removal, it halved to 28–32 million litres/day by late 2023, per Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) data, due to higher costs curbing smuggling and waste.

By 2024, consumption stabilized at 35–40 million litres/day for petrol, with diesel at 15–20 million litres/day, reflecting behavioral shifts like reduced vehicle use and CNG adoption pilots.

The policy freed N5–6 trillion annually for infrastructure, but critics argue it deepened poverty—62% of Nigerians reported worsened living standards in a 2024 Afrobarometer survey. Imports persisted, but volumes dropped 40–50%, saving $8–10 billion in forex.

Dangote’s Dawn: From Launch to Current Output

Aliko Dangote’s $19 billion refinery in Lekki, Lagos—the world’s largest single-train facility at 650,000 bpd (105 million litres/day equivalent)—broke ground in 2016, promising to end imports by 2023.

Commissioned in May 2023 by Buhari, it began diesel and aviation fuel production on January 12, 2024, after regulatory nods. Petrol followed in September 2024, with NNPC as the sole off-taker initially.

By November 2025, Dangote claims full throttle: 45 million litres/day of petrol and 25 million litres/day of diesel, totaling 70 million litres—exceeding national demand, per company statements.

This ramps up from 60% capacity in October 2025 (gasoline unit at 390,000 bpd run rate). Expansion to 1.4 million bpd by 2028 is planned, with 53% local crude sourcing in June 2025, phasing out imports by year-end.

Changes since launch: Imports fell from 100% pre-2024 to 40–60% in 2025, per reports, with Dangote capturing 50–70% market share. State refineries remain idle, despite NNPCL’s 2 million bpd target by 2027 and eyed 20% stake in Dangote.

Dr. Alaje advocates privatizing them for efficiency, warning of inelastic demand—Nigerians would pay N2,000/litre if pushed.

The Import Gap: What Remains Unsatisfied?

Post-subsidy demand: Petrol ~40–50 million litres/day (down from 60+ million pre-2023); diesel ~20–25 million litres/day. Dangote satisfies 90–100% of petrol (45M vs. 40–50M) and 100%+ of diesel (25M vs. 20–25M), per its claims.

Yet, October 2025 reports confirm imports continue—~5–10 million litres/day petrol shortfall, possibly due to distribution lags, quality disputes, or unsubstantiated claims.

This Day countered on November 10, citing Dangote’s output as “more than enough,” blaming subsidy removal for curbing consumption to 36–39 million litres/day pre-2023 levels.

Dr. Alaje urged verifiable data: “Nobody can say precisely the total volume… it’s an indictment as a nation.” If imports persist, the tariff risks shortages; if not, it cements self-sufficiency.

Online Reactions: Cheers, Jeers, and Calls for Scrutiny

X (formerly Twitter) erupted post-announcement, with notable voices split on implications—inflation risks, monopoly fears, and equity.

Supporters:

– Femi Otedola: The billionaire industrialist hailed the policy as protecting “billions invested in Nigerian refineries,” urging it shields local production without super-profits. “Kudos to President Tinubu! A smart policy to encourage domestic production.”

– Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN): Endorsed it as a “catalyst for industrial leap,” cutting import dependence and saving forex, but called for transparency to shield consumers.

– Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise (CPPE): Warned imports weaken the economy; tariff boosts refining.

Critics:

– Trade Union Congress (TUC) President Festus Osifo: “This will worsen living conditions… raise pump prices since we still import heavily.” Demanded clarification, fearing N1,000/litre reality.

– Major Energies Marketers Association of Nigeria (MEMAN): “Too high… could cripple small dealers, push prices beyond N1,000.”

– Funso Doherty (former Lagos governorship aspirant): Urged National Assembly probe, warning of deepened hardship.

– Dr. Paul Alaje (interviewee): Neutral but cautious—supports if demand met; else, inflationary. “If we can’t meet local needs, the policy should wait.”

Conclusion: Balancing Protection and Pain

The 15% tariff embodies Nigeria’s energy crossroads: shielding Dangote’s milestone—now satisfying 90–100% demand—while risking a N1 trillion consumer hit amid 34% inflation.

Dr. Alaje’s call for verifiable supply data rings true; without it, the policy teeters between empowerment and exploitation. As state refineries languish and alternatives emerge (e.g., BUA’s 200,000 bpd plant), true competition—not single-producer dominance—holds the key. For now, Nigerians queue longer, pay more, and hope the “supply side” delivers.