By any global standard, Tony Elumelu’s 20% stake in UBA is exceptionally large.

With his stake in United Bank for Africa now just above 20%, Tony Elumelu has become the single largest individual shareholder in any Nigerian bank—and one of the most concentrated personal owners of a major commercial bank anywhere in the world.

The milestone follows UBA’s recent rights issue, part of Nigeria’s system-wide recapitalisation drive. While such exercises typically dilute founders, Mr. Elumelu moved decisively in the opposite direction, fully exercising his rights and emerging with an estimated 20.7% holding.

In Nigeria, the move has been widely read as a show of confidence. Viewed through a global lens, it also raises more complicated questions about governance, regulation, and risk in modern banking.

A Founder’s Bet, at Scale

UBA is not a domestic lender. It operates in more than 20 African countries and maintains international banking licences outside the continent. That footprint demands capital well above Nigeria’s minimum thresholds, particularly the ₦500 billion benchmark for international banks.

Mr. Elumelu’s enlarged stake delivers three immediate benefits. It anchors the capital raise, signals insider conviction to the market, and ensures strategic continuity for a bank whose identity has long been intertwined with its founder’s pan-African vision.

Yet concentration of ownership at this level—one individual holding a fifth of a systemically important bank—is precisely what most advanced banking systems have spent decades trying to avoid.

How Rare Is a 20% Stake?

In the United States, it is virtually unthinkable.

At JPMorgan Chase & Co., ownership is widely dispersed among institutional investors; no individual or family comes close to double-digit control. The same is true at Bank of America, where the largest shareholder is Berkshire Hathaway, with roughly 13–14%—a corporate holding subject to strict regulatory oversight, not personal control.

In Britain and the European Union, regulators draw bright lines. Stakes above 10% trigger “significant influence” tests; holdings above 20% invite intensive prudential scrutiny. At HSBC Holdings, the largest shareholder, Ping An Insurance, owns under 8%. At Banco Santander, the founding Botín family retains cultural influence, but controls only a low single-digit equity stake.

Asia allows larger anchors, but usually without individuals. DBS Bank is nearly 30% owned by Temasek Holdings, a sovereign investor subject to rigorous governance rules. In China and Japan, banks are either state-owned or embedded in cross-shareholding networks that dilute personal dominance.

By comparison, Mr. Elumelu’s stake is closer in scale to state ownership—except that it is personal.

The Risks Beneath the Confidence

Supporters see a founder doubling down on his institution. Regulators and long-term investors see a more nuanced risk profile.

Governance concentration.

A 20% shareholder does not formally control a bank, but exerts undeniable gravitational pull. Board independence, executive succession, and strategic dissent can become harder to sustain when one voice carries such economic weight.

Regulatory exposure across borders.

UBA is supervised not only in Nigeria, but in dozens of jurisdictions. A shareholder of “significant influence” attracts scrutiny everywhere the bank operates, from fit-and-proper tests to heightened oversight of related-party transactions. Any misstep is amplified across borders.

Key-man risk.

Markets tend to discount institutions overly associated with a single individual. Illness, reputational shocks, or shifts in personal priorities can become systemic concerns when ownership and identity are so closely aligned.

Capital dependence.

An anchor investor stabilises a capital raise—until markets begin to assume that future rescues will also depend on the same balance sheet. That assumption can quietly alter risk-taking incentives inside the institution.

Illiquidity at the top.

A stake of this size is not easily sold. It locks both shareholder and bank into a long-term relationship that offers stability, but little flexibility.

These are not abstract concerns. They are the reasons regulators in New York, London, Frankfurt, and Tokyo have steadily pushed banks toward dispersed ownership over the last half-century.

Nigeria’s Distinct Path

Emerging markets have historically tolerated higher founder stakes to support capital formation. Nigeria is no exception. Yet even here, tolerance is narrowing as banks expand abroad and court foreign capital.

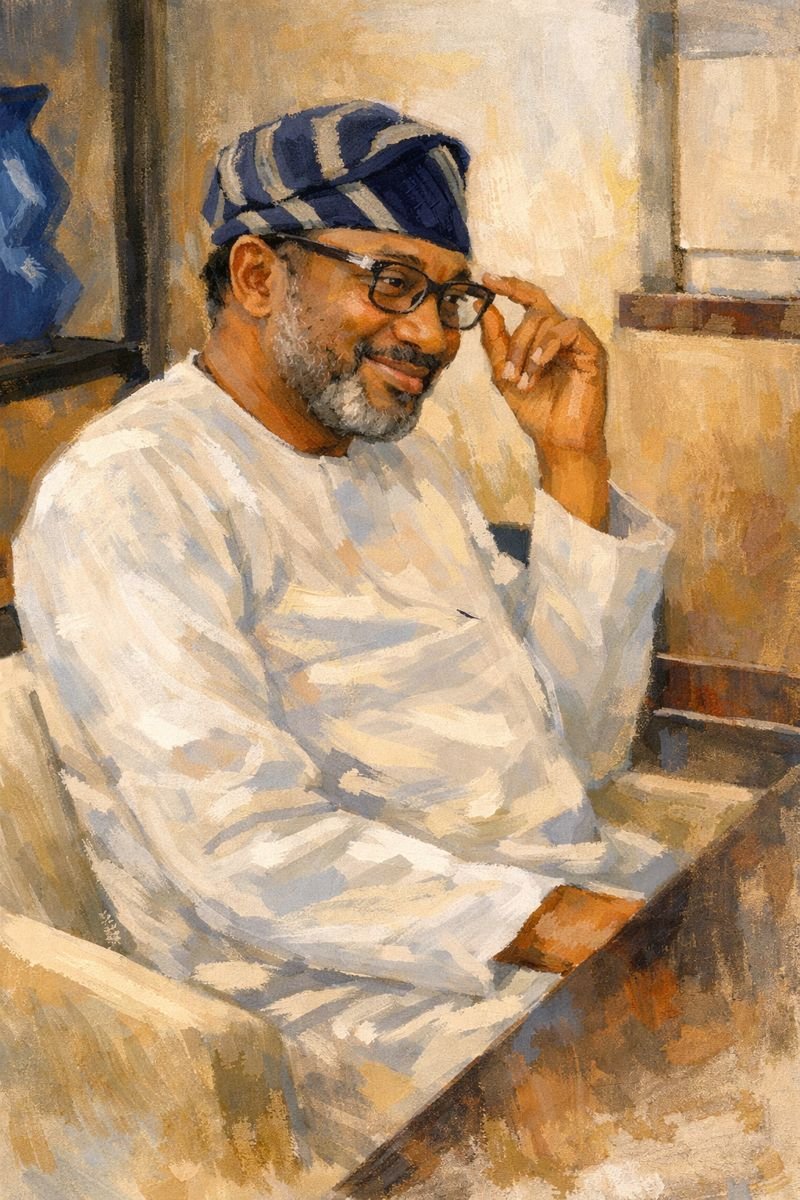

Within the domestic sector, no other banking figure has crossed the same threshold. Aigboje Aig-Imoukhuede remains below 10% at Access Holdings Plc. Femi Otedola is estimated at about 16% of First HoldCo Plc, while Jim Ovia holds a mid-teens stake in Zenith Bank Plc.

Mr. Elumelu stands alone.

A Test Case, Not Just a Milestone

For now, the market reads the move as confidence—and perhaps rightly so. But globally, banking history suggests that concentrated ownership is less a destination than a balancing act.

The challenge for UBA is not whether a founder should hold 20%, but whether governance, transparency, and regulatory discipline can evolve fast enough to neutralise the risks that come with it.

In that sense, Mr. Elumelu’s stake is more than a headline. It is a quiet experiment—one that will be watched closely not only in Lagos, but in regulatory offices and trading floors far beyond Nigeria’s borders.