It is easy, therefore, to assume that our policymakers do not know what they are about. If you add to the conversation our baked-in preference for affirmative action hiring over competence- and qualification-based recruitment, this conclusion acquires a certain inevitability. However, the regularity with which we seem to not know what we are doing would seem to suggest a greater purpose to policymaking here.

Over the weekend a slew of developments in the local economy again underlined the problem with how policymaking works here. A few of the concerns. In the design of domestic policies across the three tiers of government, and then again, even in the private sector, what roles do a full description of desirable outcomes play and when? And, arguably no less important, what is the process by which these policies are arrived at? Almost without fail, the sense that one gets each time government, or any of its innumerable departments announces a new policy initiative is of difficulties in agreeing on tradeoffs. Given that with every policy there are always going to be winners and losers, it helps to understand how government arranges the priorities around its policies, beyond the question of outcomes.

Beyond even this, there is the bit about how the diverse policies and their respective environments work together or cancel themselves out. This is as much a question of sequencing. Once the desired policy outcomes have been agreed on, and the policies consistent with these goals are fashioned out, the biggest challenge is in ordering implementation for maximum effect, while keeping costs down. The optimal route along a decision tree is the combination of several start-to-finish relationships between events and their nodes. You do not have to be a project planning expert to know that this is not one of our strongest suits as a people.

“Who has a look in and why in the design of policy?” is not a question that we have ready answers to. “What are the benefits policy aims at?” and “How big a cost would we have to bear in order to achieve these benefits?” “Who are the most likely appropriators of these gains?” and “Who are most likely to bear the costs?” “Are we willing to run with the cost-benefit dynamic as they are?”

Nor is the governance of policy areas a key national competence. “Who has a look in and why in the design of policy?” is not a question that we have ready answers to. “What are the benefits policy aims at?” and “How big a cost would we have to bear in order to achieve these benefits?” “Who are the most likely appropriators of these gains?” and “Who are most likely to bear the costs?” “Are we willing to run with the cost-benefit dynamic as they are?” or “Given the multiplier effect of any given policy are we willing to mitigate the negative externalities arising therefrom (and how) in order that we may gain maximally from the benefits?” All of these are key questions. But nearly always our policymakers have never seemed alive to any of them.

Also Read: 2023 and Nigeria’s Abiding Question of Leadership

It is easy, therefore, to assume that our policymakers do not know what they are about. If you add to the conversation our baked-in preference for affirmative action hiring over competence- and qualification-based recruitment, this conclusion acquires a certain inevitability. However, the regularity with which we seem to not know what we are doing would seem to suggest a greater purpose to policymaking here. “Are there benefits to our policymakers from the pursuit of wrong-headed programmes that are not included in the trade-offs that policymaking asks of us?” Yes. Especially if the level of corruption that the anecdotal evidence throws up is anything to go by. In which case we do not have bad policies because policymakers are not sufficiently equipped for their roles. We have bad policies because subsidiary outcomes of these are in the interests of our policymaking industry.

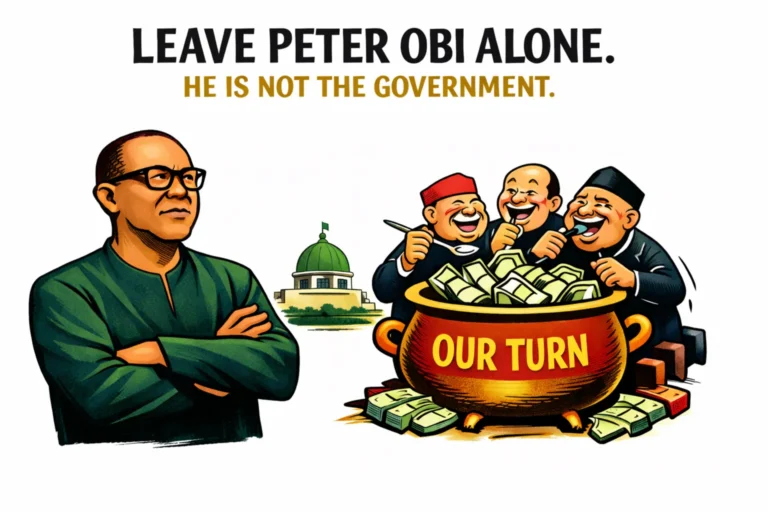

Nigeria is, instead, an ethical challenge. How do you persuade folks with access to the treasury not to insert their snouts in it? And how do we put a lid on how much each person may illegitimately take out of the coffers? Nearly always conversations about fixing this question resolve themselves into how much theft from the public coffers is “enough”.

Now, this state of affairs presents a different order of tasks for all who are minded to fix this economy. In the end, Nigeria is not an economic problem. When we ask that the price mechanism be permitted to allocate resources, whether it be in the downstream oil and gas sector or in the foreign exchange markets, the domestic opposition to this is not necessarily one that is worried about the markets’ tendencies to alienate large sections, even as an increasingly small coterie continues to make a huge profit. It is that the inefficiencies hardwired into our current processes are designed to redirect lucre into private pockets.

Also Read: Nigeria’s Banking Industry – The Past We Must Confront

Nigeria is not also a political problem, at least not in the sense in which we define politics as concerned with the making as opposed to the administration of governmental programmes. Nigeria is, instead, an ethical challenge. How do you persuade folks with access to the treasury not to insert their snouts in it? And how do we put a lid on how much each person may illegitimately take out of the coffers? Nearly always conversations about fixing this question resolve themselves into how much theft from the public coffers is “enough”. Unfortunately, because we are not a modern people “enough” is not a valid thought category. Even for money, the satisfaction from the next dollar is always going to be that much smaller than that obtained from the first one. So, even for loot, the notion of diminishing marginal utility works. Add, though, the possibility of the joy from consuming goods and services coming from the size and extent of impoverishment of the audience, then you can only take reforms of this system so far.

Uddin Ifeanyi, journalist manqué and retired civil servant, can be reached @IfeanyiUddin.