Ghana’s newly elected president, John Mahama, is setting the stage for a significant economic shift as he prepares to revisit the country’s $3 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) program. Sworn into office in December 2024, Mahama has wasted no time signaling his intent to reshape the three-year bailout program, originally signed in 2023 under the previous administration. This deal, Ghana’s 18th IMF program since gaining independence, was instrumental in stabilizing the West African nation’s finances following its 2022 debt default. However, Mahama argues that adjustments are necessary to align the agreement with current realities, a point he emphasized in interviews with Bloomberg Television and Reuters earlier this year.

To kickstart this ambitious agenda, Mahama will host a two-day “national economic dialogue” in Accra starting March 3, 2025. The event will convene a diverse group of stakeholders private sector leaders, academics, think-tank experts, and civil society representatives to chart a fresh economic course for Ghana. This follows his campaign pledge to reverse years of economic stagnation that culminated in the 2022 crisis, which saw inflation soar to a two-decade high of 54% and triggered a default on the nation’s debt obligations.

Ghana’s Debt Restructuring: Renegotiating the IMF Program

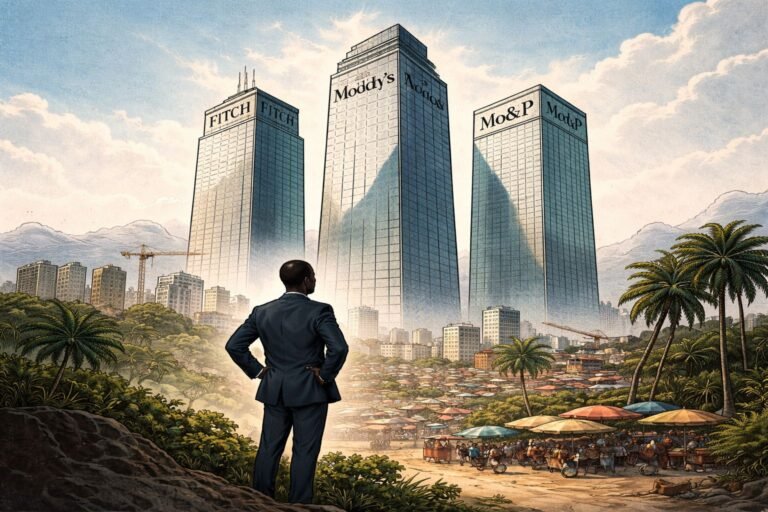

The $3 billion IMF bailout has been credited with restoring a measure of fiscal stability, imposing strict conditions such as curbing government spending, boosting state revenue, and prohibiting central bank financing of government deficits. Yet Mahama, who previously led Ghana from 2012 to 2017, has expressed frustration over the lack of input his administration had in crafting the deal. “We were not at the table when this agreement was drawn up,” he told Bloomberg Television during the Munich Security Conference in February 2025. His call for a “renegotiation” centers on tweaking the program’s terms to better suit Ghana’s evolving needs without derailing its core objectives.

However, analysts caution that Mahama’s room to maneuver may be limited. John Asafu-Adjaye, a senior fellow at the African Center for Economic Transformation in Accra, argues that the new president has “no choice” but to adhere to the IMF’s fiscal discipline mandates. “They have said they want to review the agreement, but I don’t think they have many levers to pull,” he noted. The IMF, which declined to comment for this article, has consistently urged Ghana to enhance revenue collection and streamline spending, as outlined in its latest program review. With bilateral debt payments suspended since 2022, set to resume in 2026, Mahama’s team will also need to prioritize concluding a debt restructuring deal, a key pillar of the recovery plan.

Tax Reforms and Economic Growth in Focus

Ghana’s finance minister, Cassiel Ato Forson, is gearing up to unveil a budget next month that promises significant tax cuts aimed at spurring economic growth. This move comes despite pressure from the IMF to improve the country’s tax-to-GDP ratio, which currently stands at a modest 13.8%, well below the African average of nearly 17%. Analysts see this as a delicate balancing act: stimulating business activity while meeting the revenue targets tied to the bailout. James Dzansi, senior country economist at IGC Ghana, suggests that better enforcement of existing taxes—like the poorly collected property levy, could offer a solution. “Our work shows that with a little effort, collection can increase between 90 and 100% within a year,” he said.

Economic indicators provide a mixed picture. Inflation, which hit 54% in 2022, has eased to 23.5%, still far above the central bank’s target while GDP growth is projected to rise from 3.1% in 2024 to 4.4% in 2025, according to IMF forecasts. This uptick signals a slow recovery from Ghana’s worst economic crisis in decades. Yet, businesses remain burdened by a depreciating currency, borrowing costs hovering around 40%, and hefty import levies that inflate operating expenses.

Voices from the Ground: Traders Feel the Pinch

At Abossey Okai, Ghana’s bustling hub for automobile parts, the challenges are palpable. Traders like Kwabena Debrah lament the toll of currency fluctuations on their import-dependent businesses. “The agent we work with charges in dollars, and that means we have to sell at a higher cost,” Debrah explained from his near-empty shop, where sales have dwindled. “We pass it on to the customers, and they aren’t buying as they used to.” The cedi’s depreciation has compounded the impact of import duties, leaving merchants struggling to stay afloat.

Clement Boateng, vice-president of the Ghana Union of Traders Association, echoes these concerns. While he welcomes Mahama’s commitment to streamlining taxes, he points to persistent bottlenecks at the ports. “If you go to the harbor, there are 22 fees you’re supposed to pay before your goods come out,” he said. “We complained to the previous government that the cost of doing business is too high in Ghana, but nobody listened to us.” For traders, the hope is that Mahama’s administration will deliver tangible relief where its predecessor fell short.

A Window of Opportunity Amid High Expectations

The mood in Ghana has noticeably brightened since Mahama’s election, according to a Western diplomat based in Accra. This optimism provides the president with a brief window to enact meaningful reforms before public patience wears thin. The national economic dialogue and upcoming budget will serve as early tests of his ability to translate campaign promises into action. Yet, the stakes are high: with voters and businesses alike watching closely, Mahama must navigate the IMF’s constraints, address structural inefficiencies, and deliver growth without stoking inflation or derailing the recovery.

As Ghana emerges from its economic abyss, Mahama’s leadership will hinge on striking a delicate balance, honoring international commitments while responding to domestic demands. The road ahead promises to be as challenging as it is critical, with the nation’s future hanging in the balance.