In a recent piece, The Economist turned its attention to Nigerian fashion, charting how a once largely domestic aesthetic has become a global cultural force. From TikTok trends built around the sculptural gele to diaspora-driven pop-ups in Western capitals, the magazine argues that Nigerian style has achieved international visibility—even if the economic dividends at home remain modest.

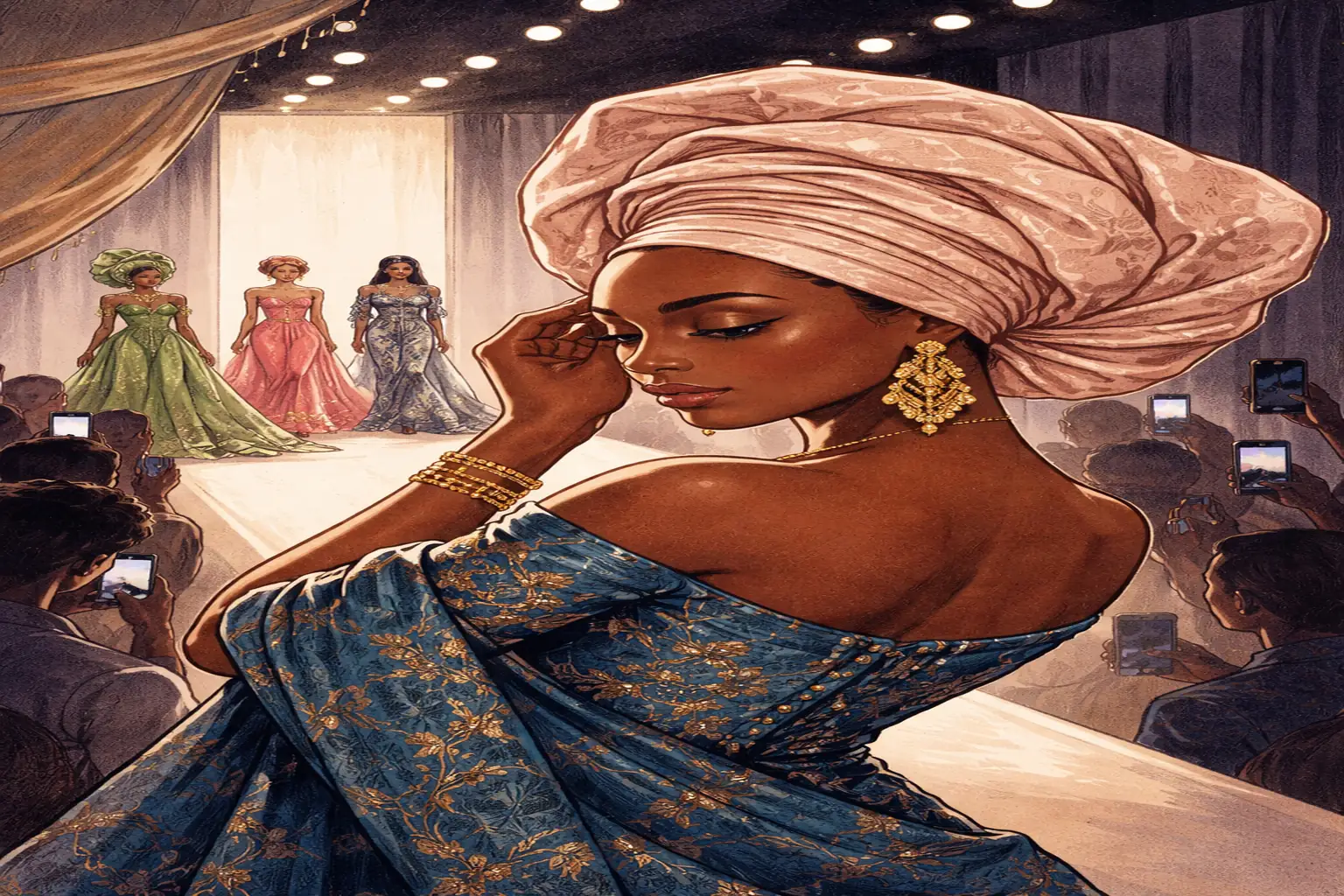

The soundbite that helped crystallise the moment came from Keys the Prince, a British-Nigerian rapper: “I’m gonna marry a Nigerian and you’re gonna wear gele to my wedding.” The lyric ricocheted across TikTok, soundtracking videos of women—Nigerian and non-Nigerian alike—being cinched into flamboyant gowns, crowned with carefully pleated headties. What was once ceremonial attire has become algorithmic spectacle.

From Local Ceremony to Global Circulation

Nigeria’s 230m people are among Africa’s most fashion-conscious consumers, with annual apparel spending estimated at up to $6bn, much of it on imports. For decades, however, local styles travelled little beyond Nigeria’s borders. That geography has shifted. As The Economist notes, diaspora networks have been decisive. Pop-up retail events in cities such as London and Houston now cater to second-generation Nigerians and curious non-Nigerians alike. Meanwhile, Lagos—the country’s commercial capital—has become a magnet for buyers, stylists and influencers during its annual fashion week.

American celebrities with no prior connection to Nigeria have worn Nigerian designers on red carpets. Teenagers order prom dresses from ateliers in Ibadan. One designer reportedly fulfilled 1,500 American prom orders in a single year. Cultural diffusion has accelerated far faster than factory output.

A Fashion That Was Always Global

In one sense, Nigerian fashion has long been cosmopolitan. Colonial trade routes introduced silky threads later woven into aso oke, the Yoruba ceremonial fabric. Akwete weaving among the Igbo reflects Indian influences. Damask used in women’s headties was originally Austrian; lace often French or Swiss, later Chinese and Korean.

What has changed, as The Economist observes, is the direction of influence. Today, adire—indigo-dyed cotton patterned with cassava starch—finds markets in Europe and North America. Coastal beadwork and elaborate embroidery appear in global boutiques. Nigerian aesthetics are no longer merely hybrid; they are exportable.

Technological shifts have helped. Social media collapses distance between artisan and consumer. Textile innovation has softened formerly rigid damask, making gele easier to tie and more wearable. Pre-tied “autogele” and machine-assisted beadwork widen accessibility. Designers such as Adebayo Oke-Lawal have showcased collections in Berlin, positioning Lagos streetwear within international fashion conversations. Retailers including Saks Fifth Avenue and Zalando now stock diaspora-linked brands.

Cool Without Scale

Yet the magazine is clear-eyed about the limits of this triumph. Textiles and apparel account for roughly 0.5% of Nigeria’s GDP. Structural bottlenecks—unreliable power, high logistics costs, limited industrial financing—impede scaling. Manufacturing at volume remains elusive.

Neighbouring Benin is investing heavily in cotton and textile industrial zones. Nigeria, by contrast, relies on a patchwork of small-scale artisans. Many have little interest in scaling up. Traditional fabrics such as aso oke are labour-intensive and fragile. Natural dyes fade; silk mildews; holes form. Authenticity resists mass production.

The result is a paradox. Nigeria’s fashion has become globally visible before it has become globally competitive in industrial terms. The country has mastered soft power in cloth and colour. Converting that into export earnings will require infrastructure, energy reform and sustained policy attention.

As The Economist concludes, Nigerians have discovered that their fashion makes them cool. It may take longer for it to make them rich.