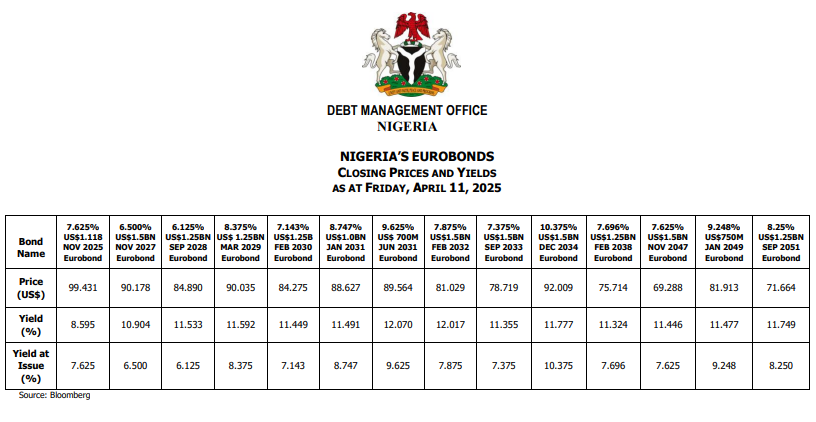

Yields on Nigeria’s sovereign Eurobonds climbed sharply across maturities last week, with investors demanding higher returns amid persistent concerns over the country’s fiscal sustainability and global risk aversion.

According to data from Bloomberg compiled by the Debt Management Office, yields on all 14 outstanding Eurobonds rose significantly above their respective issue levels as of Friday, April 11. The yield on Nigeria’s $1.25 billion September 2028 bond climbed to 11.53%, up from its original issuance yield of 6.125%. Similarly, the benchmark 2031 issuance touched a yield of 12.07%, the highest across the curve, despite offering a 9.625% coupon.

The average premium over issue yield across Nigeria’s Eurobond curve now exceeds 3.7 percentage points, reflecting heightened investor anxiety about Nigeria’s ability to stabilize its macroeconomic environment and service external debt obligations.

Prices also continued their downward drift, with the longer-dated 2051 bond trading at just 71.66 cents on the dollar, compared to its par issuance. The 2047 bond, another key long-duration instrument, slid to 69.29, pushing its yield to 11.45%.

Behind the Sell-Off

The pressure on Nigeria’s debt comes as the country grapples with high inflation, exchange rate volatility, and a burgeoning budget deficit. Nigeria’s inflation rate has declined to 24.48% after a rebasing of the consumer price index but still high enough to erode real returns and dampen investor sentiment.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), under new leadership, has attempted to stem the decline in investor confidence by sharply raising interest rates and floating the naira to reduce arbitrage and attract foreign capital. However, the exchange rate remains intermittently displays signs of lingering volatility, and the gap between the official and parallel market rates has not fully closed.

On the fiscal side, the federal government continues to run large deficits, financed partly by domestic borrowing and Central Bank advances. The removal of petrol subsidies in mid-2023 was initially seen as a signal of fiscal discipline, but rising transport and energy costs have stoked inflation. Meanwhile, efforts to ramp up non-oil revenues have yet to yield substantial results.

“Nigeria is at a critical inflection point,” said a Lagos-based investment analyst. “The government’s reforms are broadly in the right direction, but the pace and credibility of implementation are now what markets are watching closely.”

Why Bond Yields Rise

Bond yields rise when bond prices fall, a phenomenon typically driven by increasing perceptions of risk or changing interest rate expectations. For sovereign debt like Nigeria’s Eurobonds, yields tend to spike when investors are worried about the government’s ability to meet its debt obligations or when global financial conditions tighten.

When demand for a bond weakens either due to country-specific concerns or because global investors are shifting toward safer or higher-yielding alternatives, its price drops. Since bond coupons are fixed, a lower price automatically means a higher yield to maturity. Conversely, yields can fall if confidence improves and demand returns, driving prices back up.

Rising U.S. interest rates and a strong dollar often lead investors to pull funds from emerging and frontier markets, pushing their bond yields higher. In Nigeria’s case, this global backdrop has been compounded by local fiscal and macroeconomic pressures.

Outlook

“Yields at these levels reflect not just global interest rate pressures, but also a clear risk premium on Nigeria’s economic trajectory,” said an emerging markets strategist at a London-based investment bank. “Without stronger signals of reform implementation and external financing, the bonds will continue to trade at distressed levels.”

The situation is further complicated by global monetary tightening and geopolitical uncertainty, both of which have triggered capital outflows from riskier frontier markets like Nigeria. The U.S. Federal Reserve’s higher-for-longer stance has made dollar-denominated Nigerian debt less attractive compared to safer U.S. treasuries.

Still, some fund managers believe the elevated yields could present buying opportunities, particularly if Nigeria secures multilateral financing or progresses with its much-needed subsidy and revenue reforms.

Nigeria has no maturing Eurobond until November 2025, giving it a short-term buffer. However, analysts warn that unless market confidence improves, refinancing upcoming maturities could prove costly.