The Federal Ministry of Education recently announced a change in mathematics requirements for admission into tertiary institutions. After decades of requiring a credit pass in mathematics as a prerequisite for university admission regardless of course of study, the ministry has now dropped this prerequisite for arts and humanities students. The argument for this drop is that the current approach constitutes an unnecessary hurdle in the path of students who don’t necessarily need mathematical skills in their lives.

It is concerning that, once again, the government has decided to lower university entry requirements rather than working on improving the quality of basic and secondary education that produces prospective university students. Over recent years, the cutoff mark for the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME) for admission into universities has been cut from 200 down to a mere 120.

The primary justification for this consistent erosion of entry standards is the notion that students are being unfairly denied the opportunity for the university education they are entitled to. But a university education is not an entitlement; it must be earned. A decent, minimum entry barrier is essential to ensure that the system does not sink further into the abyss of mediocrity.

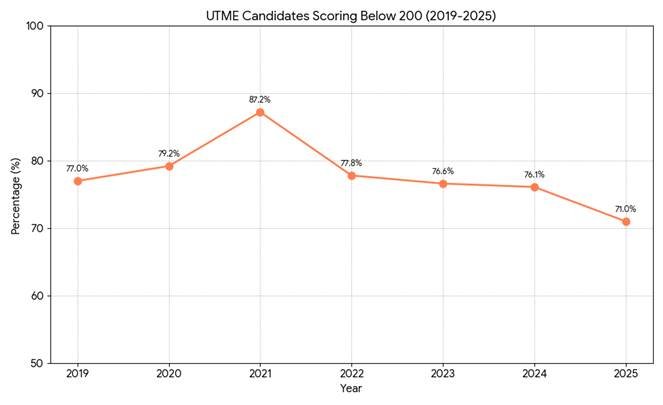

When standards are lowered, students are encouraged to not work as hard as they can as the persistently poor performance in UTME shows. Universities are struggling to fill their space because less than 30% of UTME candidates score 200 and above in the entrance examination every year. This 30% or so would have been the only pool of qualified candidates universities can draw from, but by lowering the cut-off to 120 (a mere 30% of obtainable marks), virtually all UTME candidates are qualified for admission if they have the required credits in their Senior Secondary School Certificate Examination (SSCE).

Table 1: UTME Candidates Scoring Below 200 (2019 to 2025)

Source: UTME Reports

The removal of SSCE maths credit for arts and humanities students is therefore another step towards this goal of unrestricted admission. However, this relaxation of entry requirements runs the risk of simply mass-promoting secondary school leavers to university, irrespective of their actual academic performance or ability.

This policy parallels the disastrous mass-promotion model already implemented in secondary schools, where it is now unheard of for pupils to be held back in Primary 6 for failing the common entrance examination. It’s led to a situation where 73% of children aged 7 to 14 cannot read or solve simple maths problems.

What’s the alternative?

The Ministry of Education has promised that the policy can remove barriers while maintaining academic standards. It is hard to imagine how standards can be maintained when students are told they will be promoted even without demonstrating basic capacity. Even if it is true that exceptional students in arts and humanities are being held back by mathematics requirements, why not create an exemption for only students who have shown exceptional ability in their core subject. Students with A1 in literature, government or history can have their mathematics requirement waived. This will remove a barrier for this group of students without lowering standards en masse.

Maths matters

It was the French philosopher René Descartes who said, “Mathematics is a more powerful instrument of knowledge than any other that has been bequeathed to us by human agency.” Education experts worldwide seem to agree with him, and modern education has been woven with a strong thread of mathematics. From China to the UK, mathematics is treated with utmost seriousness in the pre-university phase. China’s Gaokao exam required for university admission is around 20% maths. The SAT in the US used by many Ivy League universities is 50% maths.

In the UK, where many of our own leaders educate their children, a pass in Maths GCSE (the rough equivalent of our SSCE) is a virtual prerequisite for A levels education which is required for university entry. Furthermore, the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which benchmarks education in 81 countries and territories, focuses on testing reading, mathematics, and science among 15- to 16-year-olds.

The message is simple, mathematics matters. When our students struggle with O-level mathematics, our primary response should be to support them to pass, not to prematurely de-emphasise the subject. This policy change will inevitably reduce both enrolment and interest in mathematics across secondary schools, encouraging more students to avoid science classes entirely.

What Should be Done

The federal ministry of education should work with its state counterparts to urgently improve the quality of teaching of not just mathematics in primary schools especially. The faulty foundation that ensures kids never pick up mathematics is often laid in primary school. This renewed attention should, of course, be extended to secondary schools. So instead of lowering the university’s entry barrier, we should be boosting standards and ensuring excellent instruction, not just in mathematics but across all pre-university subjects. A strategic investment in foundational education is the only policy that can truly fix this math deficiency problem and is the only policy truly in the best interest of our country.