The United States added just 50,000 jobs in December, undershooting market expectations and reinforcing signs that the world’s most important labour market is cooling after several years of strength. Yet the unemployment rate fell to 4.4%, complicating the Federal Reserve’s near-term decision on whether to continue cutting interest rates or pause as policymakers assess the true pace of slowdown.

The report is also landing in a politically charged environment. President Donald Trump has repeatedly questioned the accuracy and independence of official statistics, a dispute sharpened by his earlier decision to remove the official overseeing jobs data.

Trump disputes the job figures — and the context of the BLS leadership shake-up

The employment report was published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Labour Department unit responsible for the monthly payrolls count. In 2025, Trump fired the official overseeing the jobs data after an earlier weak employment release, triggering public debate about political interference in economic institutions and whether data production could be pressured—directly or indirectly—by the White House.

That controversy now matters for two reasons.

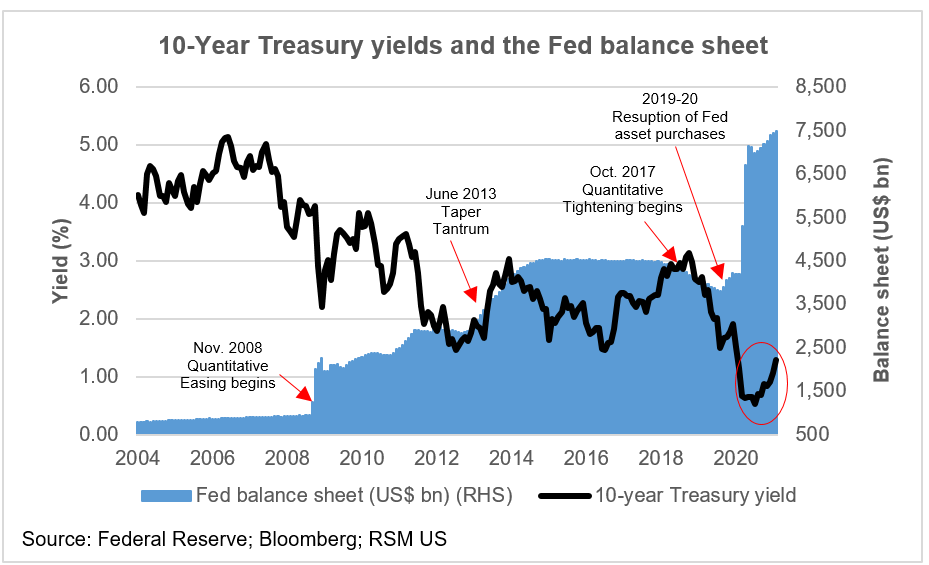

First, investors treat payrolls as a policy trigger. The jobs report influences Federal Reserve decisions, bond yields, equity pricing, and the dollar. Any sustained doubt about the credibility of the numbers can increase volatility and force markets to rely more heavily on confirming signals such as tax receipts, jobless claims, and private payroll trackers.

Second, the Fed itself has been unusually explicit about measurement risk. In December, Chair Jay Powell referenced analysis suggesting the economy may have been adding materially fewer jobs than reported. This has kept markets attentive not only to the headline payrolls number, but also to future revisions.

What the December report says — and why it still signals a cooling labour market

Key takeaways from the December release include:

Payrolls rose by 50,000, below the roughly 70,000 expected by economists surveyed ahead of the release.

The unemployment rate fell to 4.4%, down from 4.6% in November.

November payrolls were revised down to 56,000 from an earlier estimate of 64,000.

October and November data were distorted by a government shutdown and subsequent catch-up reporting, making December the cleanest snapshot of labour market conditions in several months.

Market reaction reflected the mixed message. Short-dated Treasury yields edged higher after the fall in unemployment, even as the weaker payrolls number reinforced expectations that the Fed is close to the end of its easing cycle.

The central bank has already cut rates at its past three meetings, leaving its benchmark range at 3.5%–3.75%. Powell has signalled that the bar for additional cuts is now higher, with policy described as “well positioned,” suggesting a preference to pause unless labour market deterioration becomes clearer.

Trump’s policies, the jobs figures, and the tariff channel

While monthly payrolls are not a referendum on any single policy, the December report is being interpreted through the lens of Trump’s 2025 policy mix—especially tariffs.

Higher and broader tariffs affect the labour market through several channels.

They increase business uncertainty and delay hiring. When firms struggle to forecast input costs, pricing power, or export access, they tend to slow recruitment and capital spending, often before they cut headcount.

They raise the risk of inflation persistence. Tariffs can push prices higher directly through import costs and indirectly through supply chains, potentially limiting how far the Fed can cut rates without reigniting inflation.

They reshape trade and manufacturing patterns. While some domestic sectors may benefit, the net effect can be weaker global trade volumes, higher costs for downstream manufacturers, and slower growth in trade-sensitive services.

International bodies have warned that rising trade barriers and policy uncertainty are contributing to slower global growth, with downside risks if restrictions escalate further. Higher US tariffs have also been flagged as a factor feeding renewed trade tensions, even as global growth projections remain modest.

Global spillovers: why a US labour slowdown matters beyond America

Even a modest cooling in the US labour market can transmit globally through several channels.

Tighter financial conditions may persist if the Fed pauses or cuts more slowly, keeping dollar funding more expensive and pressuring capital flows into emerging markets.

Trade volumes may soften as a more cautious US consumer and corporate sector reduce demand for manufactured imports and, indirectly, upstream commodities.

Risk appetite can deteriorate when payrolls weaken, strengthening the dollar and widening spreads for riskier borrowers, particularly commodity-dependent sovereigns.

This is why the US jobs report remains a global macro event: it helps set the price of money worldwide.

What it could mean for Nigeria: commodities, oil demand, FX, and the 2026 policy mix

Nigeria’s exposure is less about direct trade with the United States and more about global pricing and liquidity—oil prices, portfolio flows, and the dollar.

Oil and commodity demand risk

A cooling US labour market can translate into weaker global growth expectations, which typically weigh on oil demand forecasts and commodity pricing, especially when combined with trade frictions. Global projections already point to softer energy prices in 2026, with oil expected to trade below recent highs.

For Nigeria, weaker oil prices matter through lower fiscal revenue and wider deficits, given the central role of oil-linked inflows in public finances, as well as weaker foreign exchange inflows and greater pressure on naira liquidity conditions. Domestic projections already anticipate moderating commodity prices amid weaker demand and improving supply conditions.

Dollar liquidity and portfolio flows

If markets conclude that the Fed will hold rates higher for longer, or deliver fewer cuts than previously expected, emerging markets could face more expensive external borrowing, reduced portfolio inflows, and episodic FX pressure when global risk appetite turns.

The December jobs report, with a lower unemployment rate despite slowing payroll growth, strengthens the case for a pause in US rate cuts.

The policy implication for Abuja: plan for volatility, not a straight-line recovery

Nigeria’s macroeconomic managers will be watching the same question global markets are pricing: whether the US slowdown is controlled and gradual, or more abrupt but obscured by data noise and revisions.

Either way, the prudent stance is to treat 2026 as a year in which oil prices may not deliver a windfall, external financing conditions remain sensitive to US data surprises, and buffers—reserves, fiscal discipline, and realistic budget benchmarks—matter more than optimistic assumptions.