The Business of Art: Tola Wewe, Picasso of Africa

Tola Wewe, born in Okitipupa, Ondo State, Nigeria in 1959, trained and graduated with a degree in Fine Art from the University of Ife in 1983. He then went on to obtain a Master’s degree in African Visual Arts from the University of Ibadan, Oyo State in 1986. Tola Wewe worked as a cartoonist before becoming a full-time studio artist in 1991.

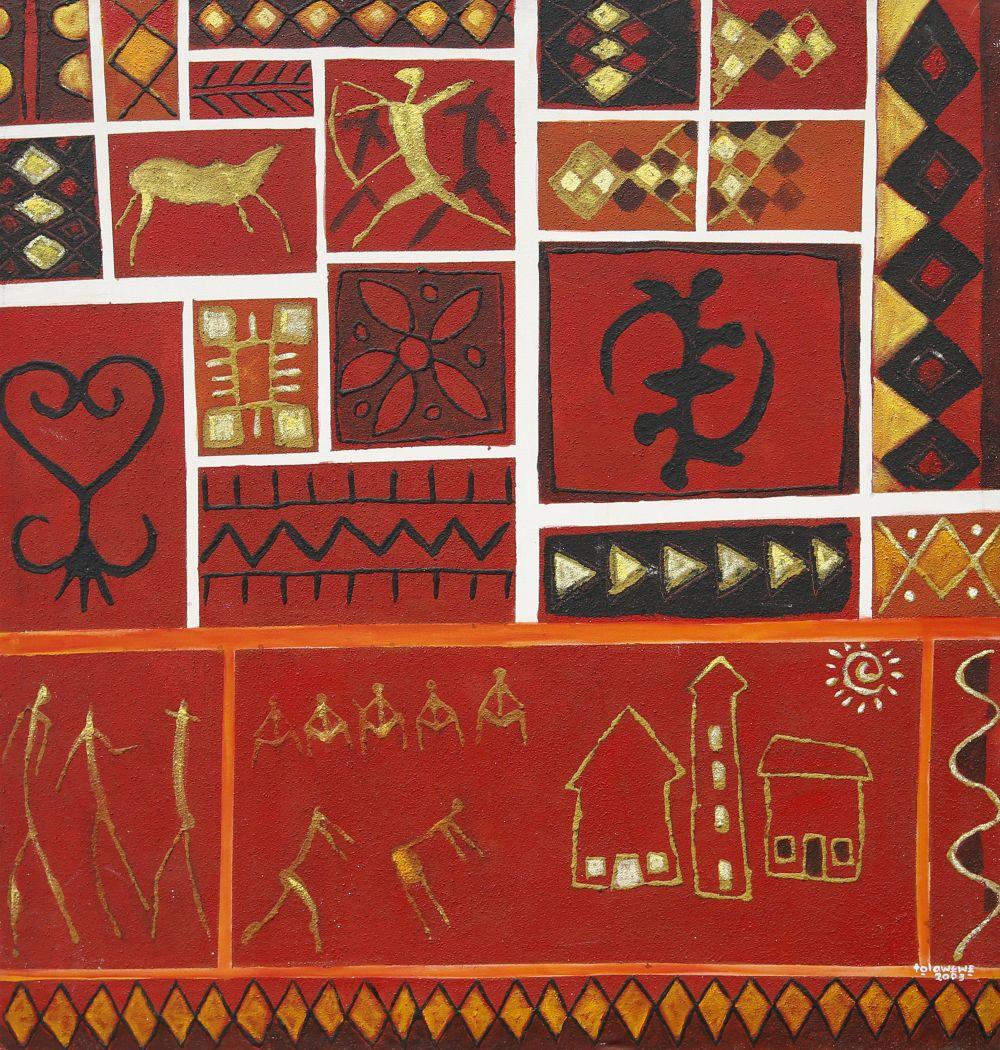

Tola Wewe, whose works are widely acclaimed for their originality, simplicity, surface texture, and mastery of colours, is considered one of the most talented minds from the African continent. Beyond Nigeria, Tola Wewe’s work has been exhibited across Europe and the US.

Why are you referred to as the Picasso of Africa?

I did my undergraduate studies at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ife. During my studies, we were made to paint still-life portraits, landscapes, and other things. After my graduation, I went to Ibadan for my Master’s degree in African Virtual Arts. It was theoretical, and my dissertation was on the Apoi Water Spirit Masks. I talked about how migratory the style was, moving from the South-South to the Central Delta region and, finally, to the West. The Apoi people are Yoruba-speaking Ijaw in Ondo State.

These masks are geometrical, combining the features of the human form with those of water animals. For example, the head of a human being and the tail of a fish or crocodile. These masks are horizontal and when worn on the head, give the impression of dancing animals on the water.

I allowed these features to influence my paintings. When I paint a human form, it may have an eye like a circle or square. So because I infuse these geometrical shapes in my paintings, people would see my painting and say, “That’s so ‘Picasso-ish’. Looking at those paintings, you would agree that they are Picasso-like. My major influence, however, was those Apoi masks. Remember that African art influenced Picasso. That’s another reason why I think they refer to my art as Picasso-ish.

Another reason is the number of artworks I churn out. I am somewhat prolific, right from my early days. For instance, during my undergraduate days, I churned out so many artworks, working alone overnight, far beyond the course requirements. This earned me the nickname iwin, which translates to “spirit”. Others worked during the day, but I would paint through the night, from 11 pm to 5 am, and then return to the hostel to sleep. In the morning, on getting to the paint-splattered studio, my colleagues would wonder ‘who did this?’

That creativity in solitude also explains why I had to leave Lagos for Ondo. In Lagos, I was distracted by the droves coming in to buy the artwork or to socialize. In Ondo, I had no distractions; I would work all through. So, I would say they also made them give me the Picasso title.

Did you start life as a professional artist in Ibadan after your Masters or in Lagos?

I have always been an artist right from my undergraduate days. I would sell my artwork to friends for peanuts. With this meager income and the support of a bursary grant, it was easy for me to sustain myself without asking my parents for money. My artwork sold between 30 kobo and N2.00 to friends and colleagues. So, I’ve always been selling artwork.

After graduation, I lectured briefly at Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo for four years before I moved to Lagos. I joined the Daily Times of Nigeria as a Senior Artist. I was cartooning and illustrating for Poise Magazine and I was doing cartoons for Times Week. I only did that for a year until I realized there was not much career progression for an artist in print media. I tried to write, but I wasn’t satisfied and so I decided to leave.

I left Daily Times and joined some friends who founded Exchequer, a colorful business and finance magazine, between 1992 and 1993. I was in charge of illustration and design. I did this for another year but I got tired and left.

While I was still at Exchequer, I became friends with Rahman Akar of Signature Gallery. He had attended my exhibition at the National Museum and bought some artwork that he needed to frame. Then we had only basic frames in Nigeria. Subsequently, he brought in some fantastic frames from London which were greatly admired. After a few trials runs in which he recorded great sales, h decided to make framing a business.

He imported a truckload of frames and set up an art workshop, Rashar Frames, at Apapa and I became his General Manager. While managing the place, I was also painting. After recording success here, he decided to establish the Signature Beyond Art Gallery. we started in a duplex at Sunbo Jibowu street, Ikoyi; the gallery was situated on the ground floor while the upper floor was his residence. As the business grew, we realized we needed a bigger space. We rented 107 Awolowo Road, then at a whopping sum of one million naira per annum, but he was convinced we would make it back. I continued to manage the business while still painting on the side until 1994 when I quit and decided to face painting fully.

He tried to convince me otherwise but I just wanted to focus solely on painting again. After a few years, I moved to Ondo.

Why did you move out of Lagos and when was this?

I moved out because of distractions. Lots of friends and clients would always come to see my work. Coupled with the stress and traffic congestion, working in Lagos became tiresome.

My move was a gradual process. Initially, I would shuffle between Ondo and Lagos; spending one or two weeks at each location at intervals. With time, it became obvious to all that I produced a better quality of work in Ondo.

How did you sell your artwork when you moved to Ondo?

I maintained a good relationship with my contacts and friends in Lagos, like Felix Osiemi, who introduced me to Chike Nwagbogu (who would later establish Nimbus Art Gallery here in Lagos). At the time, Chike was a young undergraduate passionate about marketing art, and quite energetically too. He would buy artwork from local artists to sell to expatriates in Nigeria and sells in London. When I met him, he said he had exhausted his funds but I could trust him with two of my artworks, and he would pay for them on his return. I obliged him. However, on his next trip, he was only able to sell my artwork. He started demanding more of my work and that marked the beginning of our partnership.

When I moved to Ondo permanently, I would travel weekly to Lagos just to dump all my artwork with him, and then return to Ondo to do more. I would tell him, ‘Just get N50,000:00 ready for me”. My average sales price was N10,000:00 naira per piece and I would return usually return with at least five artworks. Making N50,000.00 per week was huge for me compared to the N2,000.00 per month or N4,000.00 a month I earned at Daily Times and Signature, respectively. This cemented my decision to fully go into the practice and stay out of Lagos.

Do you know if people still have your artwork from so many years ago, when you sold them for 50 kobo or N50?

Yes, they still have them. I bought one back from a collector about two years ago. I paid N100,000.00 for it because I liked the work. He was relocating and didn’t know what to do with the painting. It was dusty and had no idea how to clean it. When I offered to buy it back, he obliged me and asked me to make an offer. I offered to pay N100,000:00 and he couldn’t resist. He bought it for N50 or so many years ago. So, I have bought back several pieces. An old friend, who was my roommate in Ife, still keeps a couple of them.

Aside from the Apoi Ijaw, are there other significant influences on your style and your work?

Yes. I’m a founding member of a group of artists called Ona. Myself, Moyo Okediji, Bolaji Campbell, Tunde Nasiru and our student, Peter Ekpo are co-pioneers. We were Ife-based artists who wanted to tap into Yoruba culture and relate this to our paintings and our work. We spelled out our philosophy, Onaism, there. We were all artists in academia, we were writing and practicing. We had our first exhibition, Ona Maiden Exhibition, at the Institute of African Studies, Ibadan in 1989, and then Ona 2: Radiance of Rhythm at the National Museum Lagos. We also held several smaller exhibitions at Ibadan and Ife. Unfortunately, during the brain drain, three of them left for the United States. Okediji and Campbell are now professors of Art while Nasiru switched to business. So, we were only two remaining in Nigeria, Kunle Filani and myself. I went into full practice while Kunle remained in academics. The Ona Group made a lot of impact on the artistic landscape.

Can you spot two or three major transitions in your style? Over the last 20 or 30 years?

The first set were those Picasso-like paintings influenced by the Ijaw water spirit masks. Cubism is about the simplification of forms. Those paintings were very cubistic. I went on with this practice for some time. My works followed a more simple approach. Before I knew it, I was almost painting like a child.

Also Read: The Big Cock Fight: Cambridge vs Benin

Then I progressed into a childlike kind of art. I would simplify my buildings the way a child between 8 and 12 years will draw. You would see this in the series I had with the turtle-like paintings where the represented forms were so simple. After that, I split into turtles, animals, styles, and others because it reminded me of my childhood. I spent my childhood in a little village. At night, especially when there is no full moon to play, we would sit outside the house and tell animal stories. I painted my experience into this to create another kind of transition.

Then early 2000 or so, I lived in Germany for some time with a girlfriend. In winter it was too cold to paint on the patio and too congested to paint inside. So I started painting small-sized artworks and started adding in little details with pen and ink on a small scale. So, I started that but Mama Nike, Nike Davies-Okundaye, started them on a small scale.

And that seems to be what you became known for a lot.

Yes. I started with small sizes and had a series of them exhibited in Germany which did so well. the ones I brought back home too. That was when I introduced pen ink to my paintings.

I would paint several miniature pieces and leave with Mama. Then one day, I came back to see Mama had added some paint designs to two of my miniatures, which looked so fantastic.

When was this?

It was around the year 2000.

Did you intend to collaborate with Mama Nike?

We didn’t plan a collaboration, she just tried her hands at it. When I saw what she had done I was impressed.

There was this fruit society; of women majority of whom were expatriates. They wanted us to organize an art workshop. They learn adire and other things from the gallery and some wanted to paint. So, they wanted a demonstration from us. I decided formally that Mama Nike and I should do a painting; a joint painting for them. I initiated the painting process with the colors and forms and Mama Nike went on to complete it. Our first artwork was auctioned and sold to a German or Belgian woman.

Do you remember how much it sold for?

I can’t remember the price. She got it from Mama Nike directly. The work was so beautiful. That’s how we started. After that day we decided to do more collaborations. Most times, I start first as she understands my moves. If I make some suggestive forms, she knows how to proceed with the painting.

What’s been the commercial impact of this collaboration on your work?

In the first instance, I’m an artist, and so is Mama Nike. We are two artists who have produced a third artist – our collaboration.

First of all, three artists mean we can now achieve what I couldn’t do on my own. This directly leads to more income. Some people may not be too comfortable with my work. But the collaboration makes them appreciate both of our work as one. There have also been huge returns as we’ve made a lot of sales. We were holding exhibitions every year, from 2009 or 2010. Currently, we’ve done up to 10 series of exhibitions.

Who are the main buyers?

I don’t follow the business aspect of me. She is in charge of that and so, knows them. I prefer just to do my work, go home, and receive credit alerts. We trust each other and so, I don’t bother myself with the running of the gallery. I just want to paint and live a good life.

She told me that the King of Morocco bought some of your artwork. Can you tell us more about that?

Yes, he bought six. He bought some of my artwork; a very huge painting, about 18 feet tall with a width of two to three meters. He also bought some joint artwork from us but she handled the transaction.

So can you tell us the higher range of your best and most prestigious artworks? Both those already sold and the ones still available.

I have one of my most priceless works and it’s still available. It’s a very long painting, about 120 meters long on canvas, longer than a football field, and can be folded. I’ve never displayed it at once you because it’s so heavy that you need about seven men to carry it. I spent about six years on the painting and completed it in 2012. I was doing it while working on other pieces. My studio was 30 meters long so I would roll and fold them at intervals.

At that time, it was the longest painting ever painted by a single artist. I don’t know if there is another one now though.

What was the theme of the painting?

It was more of a visual diary of my experience over time. There were a lot of things in it and a friend titled it Marathon. In it, I celebrated one of my friends, a journalist who died in the Liberia War, Chris Imodibe. We grew up together and were roommates in Surulere, Lagos. When he was in UNILAG, I was in OAU, Ife. We were very close; it was so painful that he died during the Liberia War. I painted his transition there. I also painted about baby factories because I’m sure maybe in the future, we may not know that there was a time in Nigeria when there were baby factories. I painted folk tales and many more. The paintings just flowed into one another. So that’s why I say it’s a kind of visual diary.

So back to its value. Somebody first tried to offer 100 million naira. I was tempted to sell, but I didn’t. It’s still with me. Late last year, a director of the African Artists Foundation suggested that maybe we could take a photograph of the painting and cut them into 120 pieces, frame them and we exhibit them together, and sell them. That will attract more money. We haven’t done it yet. But as of today, it’s still my most valuable, or my best-valued work of art.

We’ve also sold other valuable pieces of artwork but I have rarely been directly involved in the sales. ,

You seem to have been very lucky with your commercial collaborators. There is a great deal of mutual trust.

That’s true. As a result, I only have to deal directly with a few galleries and art dealers. They buy directly and resell. That saves me time and effort to concentrate on my art. I don’t have any contract with anybody. Mama Nike, for example, we’re like a family. She sells my work, takes her commission, and gives me my share. In some cases, she buys them outright and I don’t bother with how much she resells them. That’s the case with most of the art dealers I do business with.

What’s your definition of a successful artist?

In the Nigeria of today, to be labeled a successful artist, you must earn your living through your art. You must be well-known enough. You may produce very good art pieces but if you are unknown, you are unsuccessful. So, you need the media so people know you exist. Your art may be successful in the future, but you must be known today. I think those are the basic things if you want to be successful. That’s just it.

What do critics and collectors point out and like most about your artworks?

I have different kinds of collectors, and I also do different kinds of art. I have a variety of artwork and if you see some of my paintings or portraits, you will never know I painted them. There are some paintings where I combine realism with abstraction. Some people believe in that kind of art, and some belief in artwork with no images. I do those kinds of artwork too with no identifiable images.

For instance, Muslims don’t like artworks that are real. Some go for the decorative kind but not the ones with human forms where you can see the torso or the head. Some paintings just have symbols, signs, and cosmetic things.

I have different kinds of collectors. By my reckoning, there is no good or bad art because art is subjective.

Some people see textiles on canvas as art while others don’t. I’ve had some people tell me they prefer my old artwork. About two weeks ago, I’ve just sold one piece of work that I’ve done in 1994. It’s been with me for a long time but that’s what they wanted.

How much did you sell it for?

I sold it for 1 million naira. It was a small piece of artwork. It’s so funny that the buyer is so crazy about the artwork and wants a certificate for it. Nobody looked at it all these years, but that is what this young collector wants now. I always advise artists to have variety so they don’t bore people with a particular style. So, I try to vary my artwork.

You’re a major artist who is very well established but do you have artworks for entry-level collectors? For example, a junior manager in the bank who wants to invest in art?

I have all my sizes of artwork. They start from six inches to maybe six feet and eight feet.

Size influences the price to some extent. However, size doesn’t determine price alone. A piece of artwork may be small yet costly. However, the majority of the time when you look at a small artwork, the price are low. Young collectors can start here.

The bigger collectors may want the bigger paintings. So I have artwork charged at a very low amount. For $100 or $200, you can buy original artwork. I still have more expensive ones.

Some years ago, I had a manager, a French woman, Mrs. Peak. Anytime I wanted to display for an exhibition, she would advise me to bring out my more expensive pieces and leave the small pieces behind. According to her, they may just settle with a cheaper one and console themselves with the fact that they have one of the original works and not bother with the bigger ones. She had good business sense.

So, I have a variety of artwork that caters to every pocket.

Apart from Nigeria, what other markets do you sell to majorly?

I sell a lot in France, Germany, the US, and the UK. However, I’ve done more exhibitions in Germany than in any other place. I did exhibitions in Germany between 2001 and 2009 and made a lot of money there. In 2005, I had a very successful show in London that was sponsored by Guinness’ parent company Diageo, after winning the first prize, in the competition. It was during the winter but lots of people were queuing outside to come in. Even some collectors left Nigeria to buy work there.

What year was this? Would you say that was your most successful exhibition ever?

It was in 2005. Outside the country? Yes.

I had another successful exhibition in 2005 in Denver, Colorado in the US. I participated in a 3-week workshop with special kids, organized by a non-profit organization. I used sawdust, glue, and paints to work and play with the kids with challenges. Some of the teenagers had gone to jail about three times.

Also Read: Is this the Most Important Art Show Ever Seen in Africa?

At the end of the workshop, we sold all the kids’ artwork and mine. The organizers were in a dilemma when they made a profit in the end. I was offered a job immediately after because they were so impressed, but I declined. I didn’t want to go back to work for anybody. I enjoyed my freedom. I could always come to the US and go back, so I didn’t need a job.

The highlight was the feel-good factor of the entire experience. The kids were happy that people could appreciate their work. It was a good moment to see people buy their work as first-timers. Two of the kids were adopted. An African American guy developed a positive perception of whites through the experience, modeling on the white gallery handler.

Some of the kids were challenging during the program and swore at me but by the end of the program, we were all happy with each other and they mailed me after. They wanted me back. I was very happy. So, for me, that was a very successful exhibition. Their website is PlatteForum.

What other Nigerian artists do you collect?

There are several of them. Nigeria is so blessed with great artists. The visual arts, music, and performing arts; are blessed.

Are there any specific younger artists you admire, and so, collect their works?

There are several; too many to mention. One of them is not so young, and he’s not academically trained. He’s a carver. I have collected a couple of his works, about four, and I still collect. He’s in Ife and his works are so fantastic. His name is Taiwo, but he normally goes by the name Ogoji.

I recently commissioned him to do one work that is 14 feet, a whole log of wood. That’s a major job and I paid a lot for it. Most people feel that you have to go to university or read Fine Arts before you can become an artist. However, that’s not the case. The guy is so good and is a case study. Mama Nike is another example of someone who isn’t academically trained. Yet she’s made so much impact in the practice and promotion of art. She does adire and also paints.

She sees art differently and displays them differently from the Western-trained collector or galleries. Some would say that her gallery is so congested, but that is her style. There is no special formula for display. I see the combination of everything as the juxtaposition of things together. I look at the whole thing as part of the appeal.

Another artist I like is Olu Amoda. He’s not young but he’s a fantastic artist. I like the simplicity of forms in his sculptures and the way he uses metal and other materials in his work.

Do you collect his artwork too?

No, I don’t. I can’t afford him. I’m looking forward to buying his work, though.

Couldn’t you exchange with him?

I know that’s possible. He offered some years ago but at that time, I didn’t know what to do with them. But I know I can always get hold of him. He’s one of the artists I admire very much. I also like Alex Nwokolo. He trained at Federal Polytechnic, Auchi.

What can we do more as a society to improve the appreciation of art and also the commercial value of art?

It’s not just about the present, it’s about the future. Most of the places we visit in Europe are focused on art pieces produced, collected, or commissioned in the past. Today, the art generates income for investors. Crowds queue to tour the Louvre every day, generating massive revenue for France. The art on display there was once collected by some individuals. In Paris, most tourist centers are art-centered.

Our society must invest in art. We are so blessed with prolific artists in both performing and visual arts. We can establish a museum for all Nigerian arts, notwithstanding the cost. For instance, we can curate music from early musicians to contemporary artists. We may be long gone before it starts generating income.

All of that is a result of an investment. We don’t have functional museums in Nigeria. Mama Nike is bringing art to many people. If we want to promote that, it’s beyond individuals acting as pioneers. The government has to make a conscious effort to acquire these things and keep them somewhere. It’s a long-term investment. People will pay for merely coming in and going out. If there are souvenirs for them to take away; crested cups, paintings, books, or locally crafted pieces of jewelry; people will pay.

I see your point. It’s something the Nigerian or Lagos government should do. As a state, it’s recommended you have at least five pieces of artwork from every major artist over the last 60 years.

Exactly. But they are not doing that. We don’t have a museum. They recently tried to build one here in Lagos but they converted it into shops. It was supposed to be a National Museum but it was never completed. We don’t have museums. Every weekend this place is crowded because people don’t have anywhere else to relax. People want to go to places like this; look at the artwork and reflect. Most come here regularly but this place is too small. The artworks here can occupy a space 10 times this size with sections.

I was telling some people the other day about art and medicine. Art is curative. Even a practicing doctor needs to be creative to succeed. It’s not just about your competence and brilliance as a doctor, your bedside manner and speech have to be creative.

We are naturally gifted in Nigeria so why don’t we capitalize on that? Right now, they are struggling to retrieve the artworks looted many years ago and sent to Europe and America. Some of those artworks were produced here in Nigeria. If they were here, we would never have made any money. That’s something they fail to realize.

Do we have an ecosystem of galleries that can cater to the artwork we want to be returned?

There’s no museum to house them. The Louvre houses artworks from all over the world. The first time I visited, I was in a kilometer-long queue to pay to see Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. It’s a small painting with many people queueing to see it and it’s worth millions of dollars.

So, there are two ways we can improve the appreciation of art in our society. We need to increase investment and promote the teaching of art in schools. An ex-governor once fired all the Yoruba and Fine Art school teachers in his state because he felt the subjects were unnecessary. You can’t be a very good architect or engineer without the ability to visually interpret what you intend to construct or build. Art is basic to development and technology.