Today’s agency banking scene reminds me of Telcos in the early 2000s and gambling in the 2010s – there are kiosks everywhere

If you have lived in Nigeria over the past three years, it is impossible to miss the explosion of banking agents in kiosks providing access to financial services. They were previously a “rural” phenomena, in the sense that they were mostly needed in places with limited banking infrastructure such as ATMs and bank branches. Now they are at the heart of financial services delivery to millions of people, sweeping through both rural and urban Nigeria.

The services offered by these agents range from the basic to the sophisticated – withdrawals and deposits, bank account opening, BVN registration, instant transfers, airtime purchase and bill payments. The cash deposit option has so much potential. It will open up mobile money to Nigerians as majority – 80% according to EFInA – already have mobile phones. Specifically, 61% of the financially excluded have mobile phones. I have only used the withdrawal option at a 1% transaction fee. I liked the ease and speed of transactions.

As we all know, using ATMs can be difficult even when the reach is good. While I can trek to a nearby agent to withdraw, it will cost me money to go to the nearest ATM in my area. ATMs are also not reliable because many times you approach them hoping that money is in them, that the network is good and that your debit card will not be rejected. All things considered, it is cheaper for me than going to the ATM. I suspect this is the case for many Nigerians.

What is really exciting is that agency banking offers even more possibilities beyond the basics given that agents now serve as the last mile for financial services. Perhaps insurance, credit, wealth management and other financial services can be delivered through them in the near-term.

Before I discuss this topic in more detail, I must mention that its potential development impact (poverty and employment) is one aspect I am eager to explore. Unfortunately, it is the last section of this essay, so you know what to do if you are interested.

Bringing back the 2000s

The only time this reminds me of is the early 2000s. Who can forget the green, yellow and red umbrellas that lined the streets and the ecosystem that formed around them? They allowed people to use their phones to make phone calls for a fee and sold recharge cards. How many Telco agents did we have then? Banks and FinTechs later ate their lunch.

Perhaps that conclusion was hasty. There is a more recent phenomenon it reminds me of: the explosion of betting kiosks all over Nigeria. How many do we have now? It is hard to put a number on this because I did not see any useful data on the penetration online.

The ecosystem around kiosks is also interesting. There is a high chance that betting shops would allow you to watch matches for a fee. There is no doubt that you will see a vendor selling food/snacks to the hungry nearby.

The use case of kiosks for Telcos, betting and recently, financial services, remains as strong as it was in the 2000s. Some would recognise that as an indication of slow development but it works. It brought services to the doorstep of people, simplified it, and made it cheaper.

Also Read: Mastercard, MTN in Partnership to Expand Digital Payment Across Africa

It solved the infrastructure problems too. For Telcos, many Nigerians could not afford mobile phones (and/or sim cards) and the banking system was not sophisticated (they needed Telcos anyway for USSD and internet to work) enough to allow them buy airtime through their phones in the early 2000s. Similar issues resonated in betting decades later as many people lacked access to the internet and found it difficult to fund their accounts, place bets and track them.

Are these problems different for financial services today? No.

Nigeria’s Huge Banking Infrastructure Gap

Poor banking infrastructure is a big problem. The CBN reported that Nigeria had 5,797 bank branches, 9,958 ATMs and 11,233 POS terminals as at 2010. The numbers have worsened almost 10 years later when you look at absolute figures and compare to our fast growing population. Bank branches fell to 5,432 in 2019 despite a target of 7,850. POS devices peaked at 217,283 in 2018 but moderated sharply to 186,774 in 2019, nowhere near the target of 795,858. Finally, ATMs peaked at 18,910 but fell to 17,518 in 2019 despite a target of 58,241.

It is hard to overlook the gross failure even if we attest to the improvements. And I do not believe the increased adoption of digital banking justifies the lackluster performance as many Nigerians do not still have access to this channel. I remember spending almost 10% in transaction cost to withdraw using POS in Yala in Cross River during my NYSC in 2016/2017 because there was no bank in the entire local government. In the end, the success of agency banking will also be partly determined by the impact it has on rural Nigeria.

This banking infrastructure problem is what should have driven the early adoption of mobile money and agency banking in Nigeria, like in countries that have accelerated financial inclusion. After all, peer countries that have made remarkable progress in financial inclusion also have terrible and deteriorating banking infrastructure. See the comparison for bank branches and ATMs in Kenya and Nigeria.

Agency Banking in Numbers

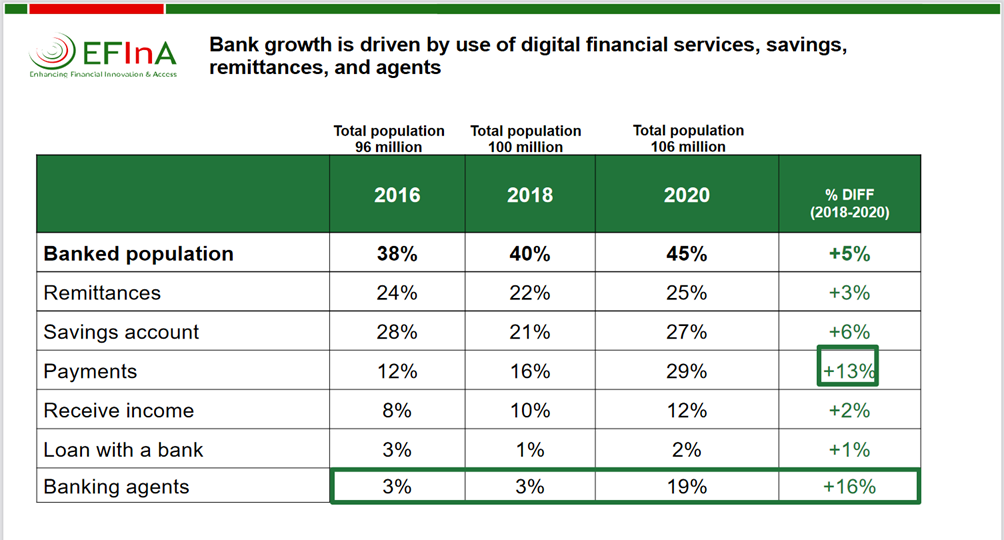

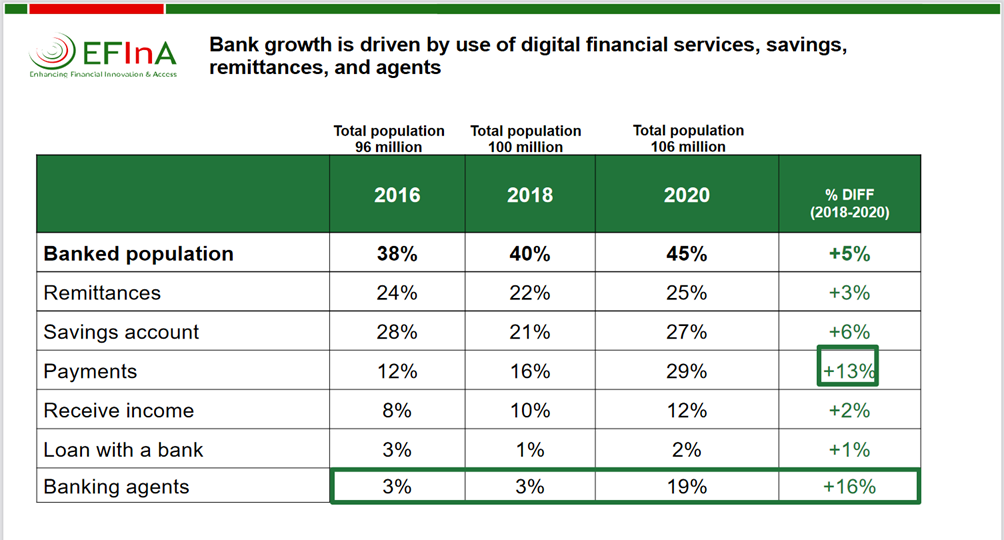

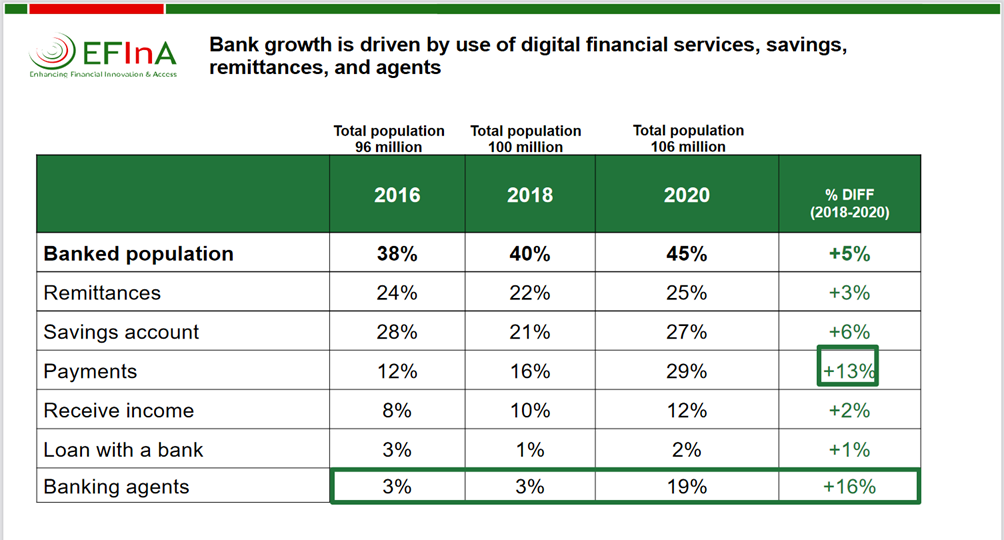

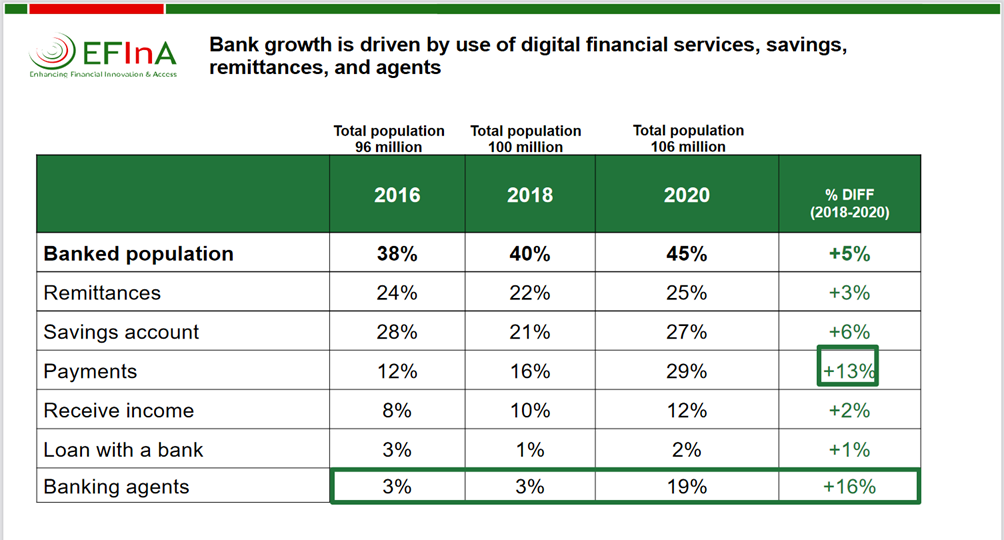

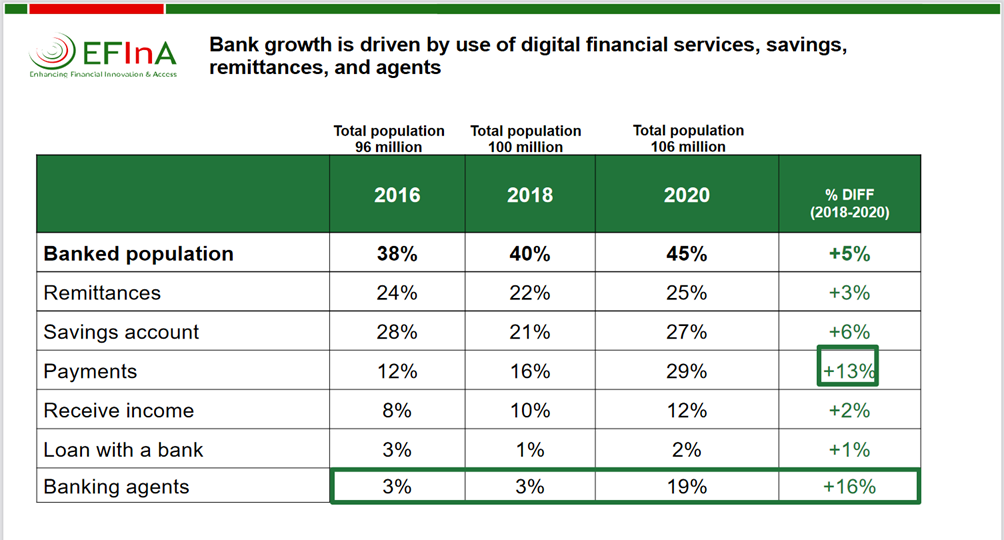

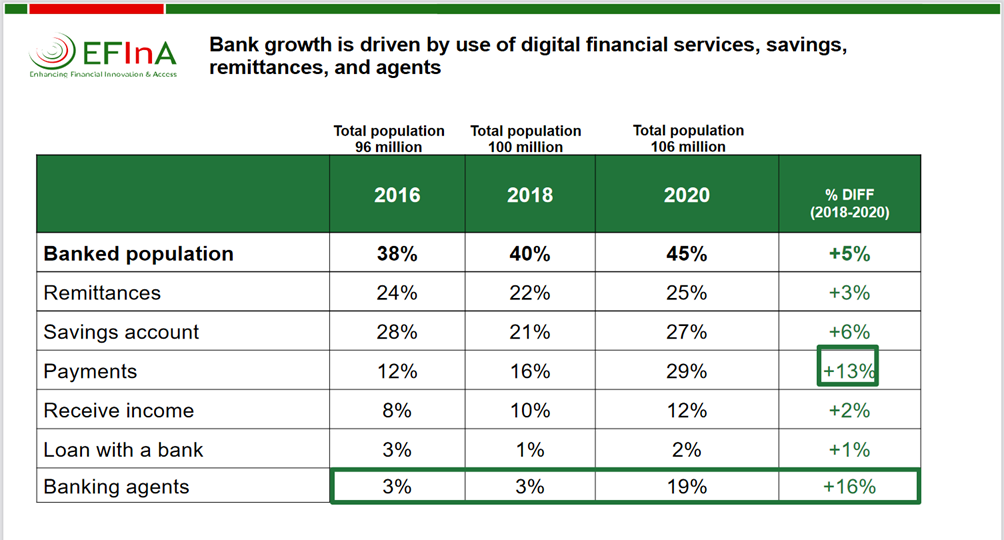

Investment into the agency banking space is increasing at a rapid pace. And it is a party for everyone. The regulator, banks, FinTechs and Telcos are all active in the space, which should ensure full interoperability (does this already exist?). This is a good development as many of the initial mobile money operators deployed agents at a slow pace. The remarkable growth recorded between 2018 and 2020 makes this even more obvious. In 2020, 19% of the adult population had access to financial services through agents compared to 3% in 2016-2018.

There are estimates suggesting that access points have grown to over 500k+ across Nigeria as at 2020. The Shared Agents Network Expansion Facilities (SANEF) scheme claims to have grown their agent network to 236k+ in 2019 from less than 40k in 2018. There is no update on their progress as at 2020 as the CBN is yet to publish the annual report on Financial Inclusion (maybe they were waiting for EFInA’s 2020 survey results). I am not sure CBN’s data captures penetration across board because SANEF works only through 21 banks and 23 super agents including the likes of Interswitch, Paga, TeamApt and E-Transact.

Opay and MTN are two players in that space without partnership with SANEF, at least from what is listed on the “partners” section of their website. Opay has found success in this space after many misadventures – food, transportation and others. They claim to have over 400k agents as at March 2021 from 290k in February 2020. Word on the street is that their next raise would make them a Unicorn. While we cannot attribute this solely to their agent banking business, it probably strongly supports their valuation. BusinessDay reported that MTN deployed over 100k agents in 2020 alone.

I am not an expert in this space but I suspect that the pace of deployment would accelerate going forward. Agency banking is not sexy but it works.

Agency Banking and Financial Inclusion

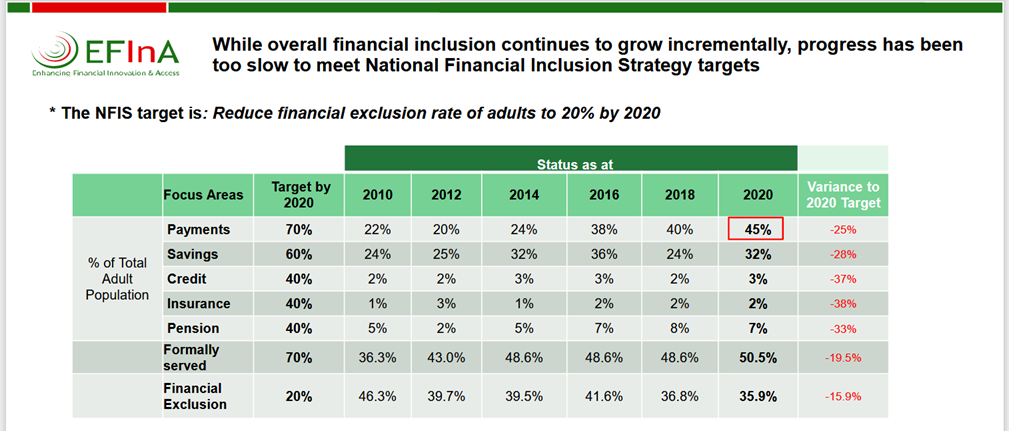

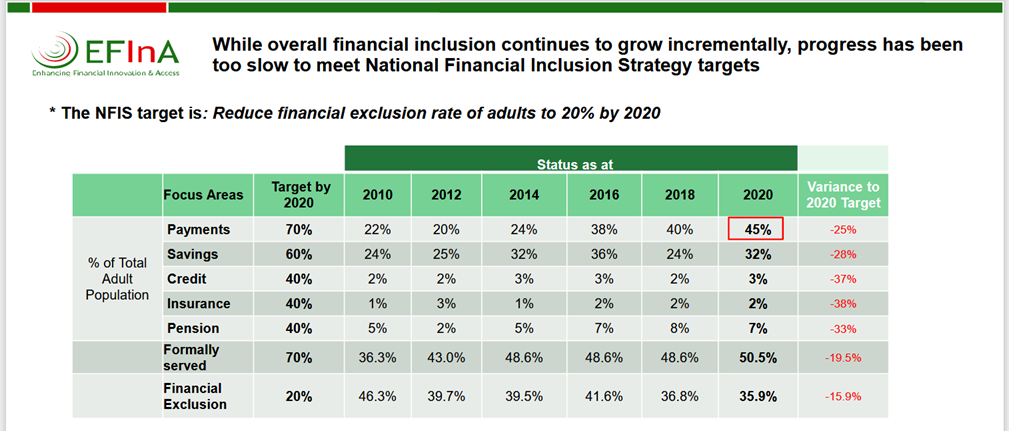

The CBN’s ambition in 2012 was to increase the financial inclusion rate to 80.0% or to lower the exclusion rate to 20.0% by 2020. Progress towards this target has been remarkably slow across all measures.

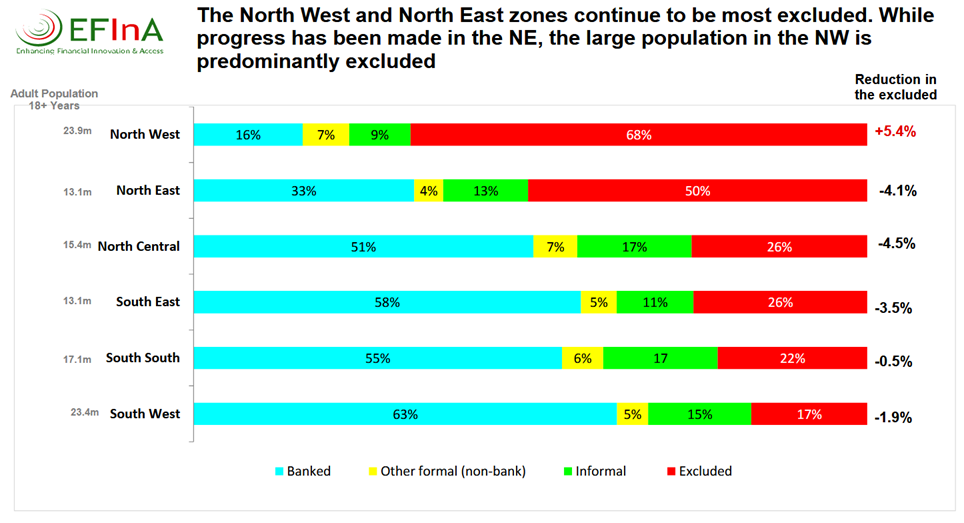

Fortunately, EFInA recently released the 2020 edition of their Financial Access Survey which provides up-to-date data. The CBN missed this target as the financial inclusion rate stood at 64.1% and the exclusion rate at 35.9% in 2020. What we have seen over the past decade is a steady improvement but what is required is radical growth.

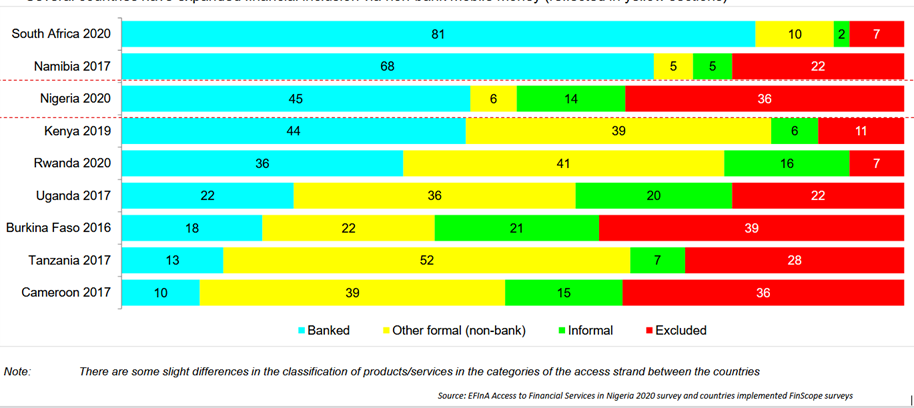

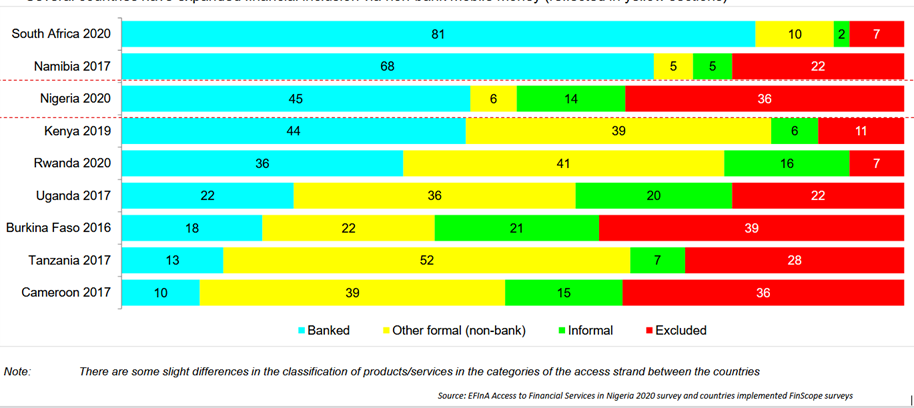

The weak approach of the CBN to supporting innovation that would transform financial access is the main culprit for under-performance. Initial regulations prevented Telcos from fully participating, until lately that rules are being relaxed. A look at peer countries shows that radical transformation in places like Kenya was powered by the Telcos through non-bank mobile money. MTN and Airtel, the largest operators in Nigeria, have incredible experience in this space across Africa.

However, MTN only just obtained the Super Agent licence and is yet to receive the licence for Payment Service Banks (PSBs), just like Airtel. Peers with less market share and indigenous players such as 9Mobile and Glo have obtained theirs. It seems the CBN is not serious yet. Maybe the recent EFInA report would convince them to think bigger, but I will not hold my breath.

Potential Development Impact

I have been itching to start this section of the essay. Bringing back my commentary on the 2000s, what was most remarkable about the telecoms boom in the nascent phase was the amount of indirect jobs it created through the kiosks.

I don’t have the actual data but I suspect more than a million jobs were created within a very short time. The agency banking boom is repeating job creation at a similar pace and scale. The only problem is that like the telecom kiosks, this could be short-lived and the jobs are of low productivity. It does not require special skills nor does it improve human capital. But we are in a country with scant economic opportunities, so we cannot be choosers. The impact will be significant for many people without good enough opportunities.

I have thought long and hard about what has had a similar impact on employment recently and nothing comes to mind. Some people might be tempted to mention the FG’s N-Power scheme but that was even limited in reach as only 500k people benefited. The opportunity also only lasted for a year per candidate. The opportunities in agency banking could surpass that given their longevity in similar countries. I have no expectations of the kind of development that would make them redundant anytime soon in Nigeria.

What potential impact can this have on poverty?

Within the industry itself, it probably won’t have a significant impact because the job opportunities will be limited relative to the scale of need. We are in a country with 40.1% poverty rate or 82.9 million poor people as at 2019. Throw COVID-19 into the mix and we are probably worse off. However, for the few who are lucky to find jobs in the space, it could make a difference. I am not sure what the daily income is like for kiosk operators but the poverty line in Nigeria is only N137,430/per year. Poverty intensity – which measures how far off the poor are from the poverty line – is also quite low at 12.9% (N17,728/year) nationally. What this means is that even small increases in income will count.

That said, financial inclusion is considered important for development. So even beyond the direct jobs created, it has meaning for people who are able to access financial services through agents. These people could run into tens of millions. It would help support their business, everyday transactions and make their lives better. Add saving, insurance and credit to the mix and you have potentially bigger development outcomes. I cannot measure this so my commentary is limited.

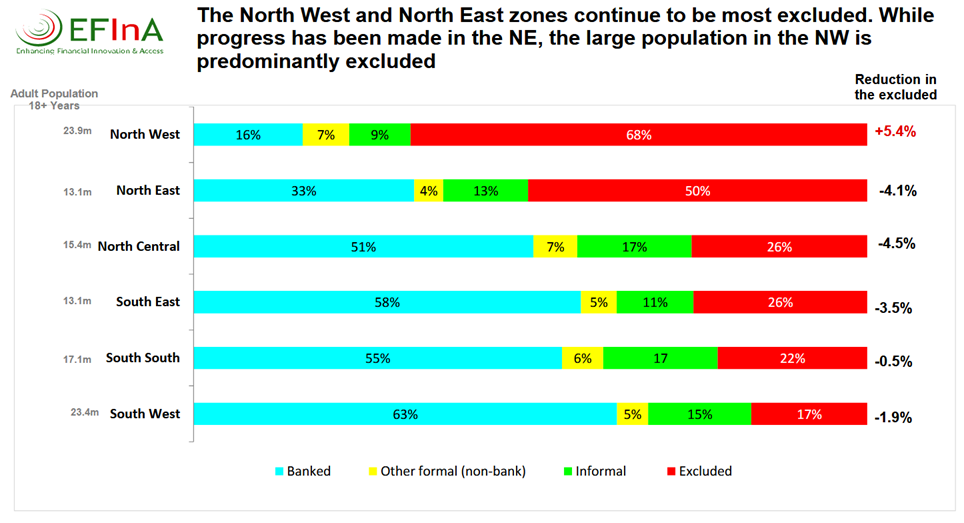

But there is a small problem. I don’t know the reach of agency banking across regions and rural communities for now. That would determine how impactful it will be overall. After all, poverty and financial exclusion are concentrated in the rural and Northern parts of the country. Who knows even if there is enough demand or start-up capital to support a lot of agents in those spaces? What about the infrastructure required to support the agents? So many questions worth exploring. I hope we see a proper study into the economics of agency banking and the development impact in a few years.

What I know for sure is that it holds a lot of promise. Access to financial services, especially when extended to credit, savings and insurance, is life-changing. However, the truth is that for agency banking to have a dent on financial exclusion in Nigeria, the reach must extend to the Northern and rural parts. We can only hope that policymakers are thinking in this direction.