When Aliko Dangote recently renewed calls for a ban on imported refined petroleum products, the demand landed in an industry already on edge and in the middle of an increasingly public dispute with the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA).

Dangote’s argument was familiar: oil marketers, he said, are importing substandard fuel into Nigeria, damaging engines, undermining local refining, and threatening energy security. The NMDPRA, for its part, has maintained that imports remain necessary to meet national demand and that the downstream market must remain competitive and adequately supplied.

Few would dispute the seriousness of fuel quality concerns. But the question Nigeria must answer is not whether standards matter—they do—but whether banning imports is the right response. A closer look suggests it is not.

A ban that appears convenient

Dangote’s call raises an uncomfortable question of consistency, particularly in light of his recent exchanges with the NMDPRA.

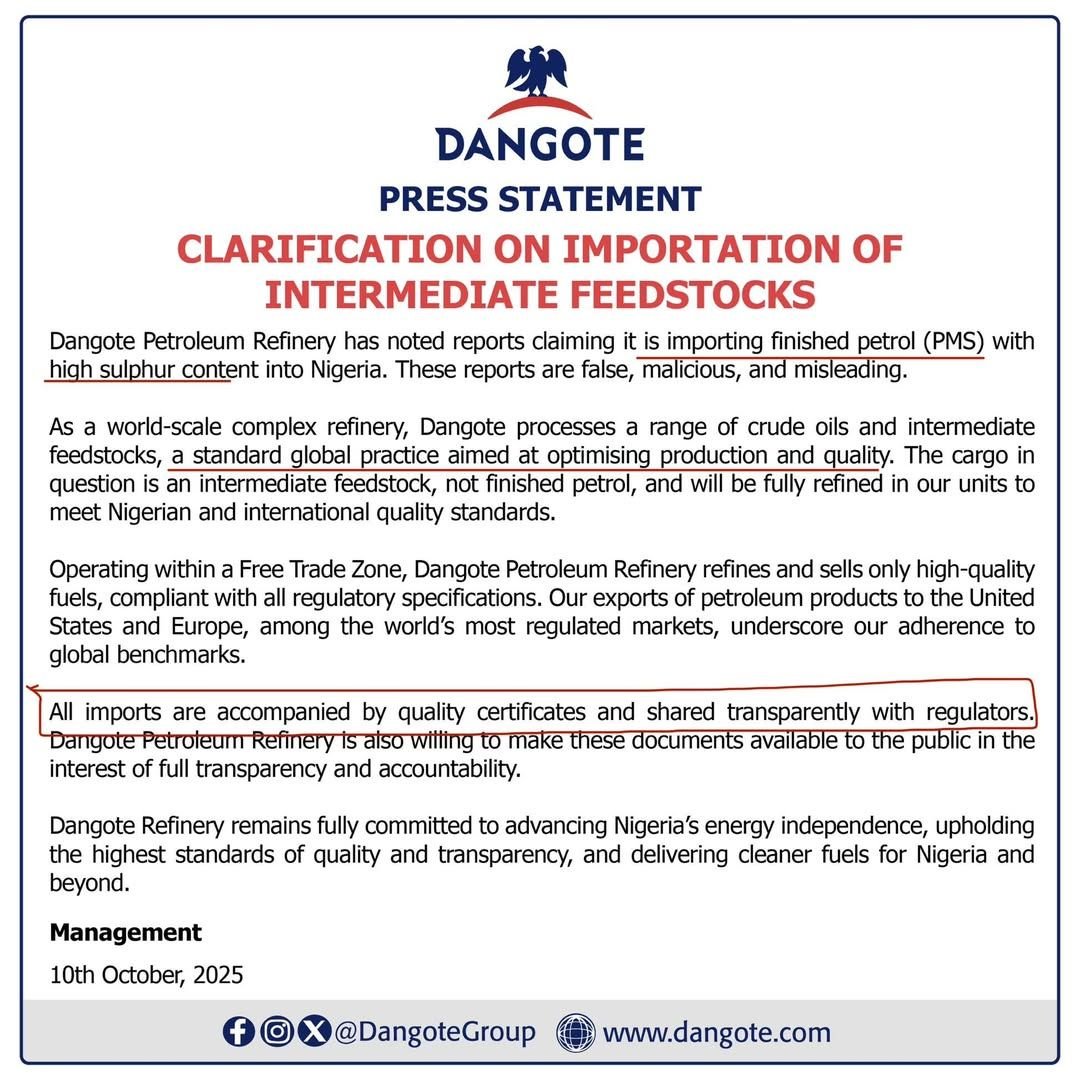

Only weeks ago, his own refinery was caught in a public dispute over claims that it was importing petrol with high sulphur content—allegations that circulated widely and drew regulatory attention. Dangote responded forcefully, explaining that the cargoes were not finished petrol but intermediate feedstocks, a standard global refining practice. He provided documentation, emphasised transparency, and invited regulatory scrutiny.

At no point did the NMDPRA propose banning Dangote’s imports. Instead, the debate—correctly—centred on verification, certification, and regulatory oversight. The assumption was that allegations should be resolved through testing and disclosure, not prohibition.

Now, with Dangote accusing oil marketers of importing substandard fuel and implicitly faulting the NMDPRA for permitting such imports, the proposed remedy has shifted from regulation to outright bans. The contrast is difficult to ignore. When scrutiny affected Dangote, the solution was transparency. When scrutiny affects competitors, the solution is exclusion.

The real problem is enforcement, not imports

Nigeria’s downstream challenge is often misdiagnosed. The presence of imports is not the problem; weak enforcement is.

If substandard fuel is entering the country, it signals regulatory failure—at ports, laboratories, and in post-clearance monitoring. Those functions fall squarely within the NMDPRA’s statutory mandate. None of these failures are resolved by shutting the border.

History also offers caution. Import bans in Nigeria’s oil sector have rarely produced quality or efficiency. Instead, they have tended to create scarcity fears, discretionary waivers, rent-seeking opportunities, and regulatory opacity—conditions that ultimately weaken investor confidence and public trust.

It is telling that when Dangote’s refinery was accused, neither the NMDPRA nor policymakers suggested banning feedstock imports. The logic was straightforward: quality disputes are regulatory matters, not trade wars. That logic should not change simply because the accused party is different.

Quality control needs regulation, not protectionism

If Nigeria is serious about fuel quality, the tools already exist—and they sit with the NMDPRA.

What is required is a credible enforcement regime: independent testing of all imported fuel at ports, clear sulphur limits aligned with national standards, transparent publication of test results, and swift penalties—including blacklisting—for any importer caught dumping off-spec products.

Such a system would protect consumers and engines without sacrificing competition or tilting the market toward any single producer. Crucially, it would apply equally to everyone—importers, marketers, and domestic refiners, including Dangote.

Why competition still matters

The Dangote Refinery is undeniably a strategic national asset. But scale alone does not justify regulatory insulation.

Even with a mega-refinery in operation, competition remains essential for price discipline, supply resilience, and efficiency. The NMDPRA has repeatedly warned that local production has yet to consistently meet national demand, a point Dangote disputes but which remains central to the regulator’s cautious stance on imports.

Imports—strictly regulated—also provide a safety valve during refinery ramp-up, maintenance shutdowns, or crude supply disruptions. These are operational realities acknowledged across the industry, including by the regulator itself.

A premature import ban risks turning industrial policy into market protection, with consumers ultimately paying the price.

The wrong tool for the right concern

Dangote is right to demand high fuel standards. On that point, there is no disagreement. The NMDPRA, too, is correct to insist that market stability and supply adequacy matter.

But the solution to quality failure is not prohibition; it is enforcement.

Nigeria does not need fewer players in its downstream market. It needs a stronger regulator, transparent testing, and rules that apply equally—whether the operator is Africa’s richest man or a mid-sized fuel importer.

The lesson from the Dangote–NMDPRA standoff is clear. When quality disputes arise, the answer is verification and accountability, not bans calibrated to whoever is winning or losing the market at a given moment.

A rules-based system, not selective protection offers Nigeria its best chance at clean fuel, fair competition, and durable investor confidence.