The University of Cambridge has formally transferred legal ownership of 116 Benin artefacts held at its Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) to Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), marking one of the most significant restitution decisions by a British university to date.

The transfer follows a formal request submitted by the NCMM in January 2022, seeking the return of objects taken during the British military expedition that sacked Benin City in 1897. Cambridge University Council approved the claim, after which authorisation was granted by the UK Charity Commission, clearing the way for the legal handover.

Under the agreement, the artefacts will be held by the NCMM under a management framework with the Benin Royal Palace. While physical transfer will be arranged in due course, 17 of the objects will remain in Cambridge on loan and on public display at the MAA for an initial three-year period, ensuring continued access for students, researchers and museum visitors.

Objects Taken in the 1897 Punitive Expedition

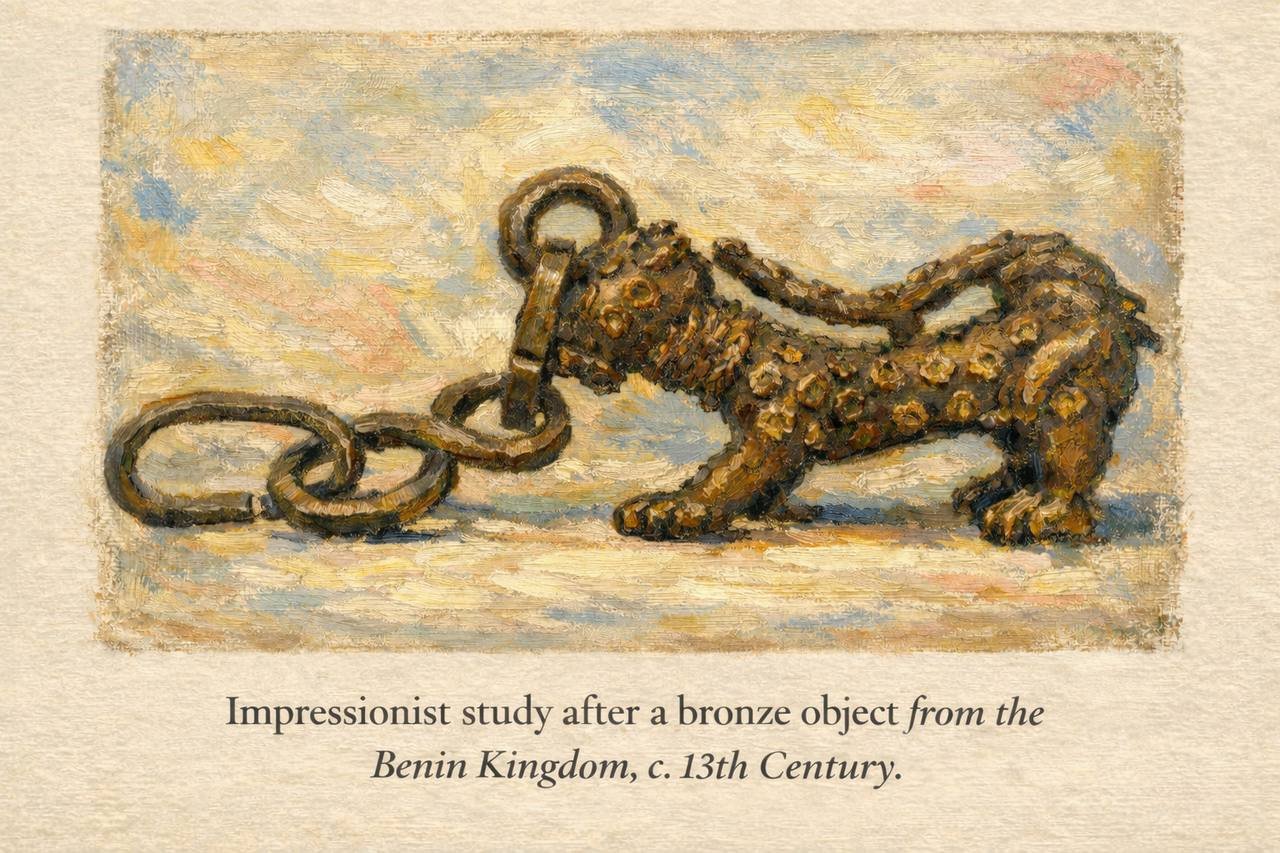

The collection—primarily brass works, alongside ivory and wooden sculptures—was removed from Benin City during the so-called “Punitive Expedition” of February 1897, launched by British forces following a violent trade dispute the previous month. These works include high-relief figures, ceremonial jewellery and sculptural representations such as leopards, symbols of royal authority in Benin culture.

Cambridge’s decision aligns with a growing international movement among museums in the UK, Europe and the United States to return cultural objects acquired through colonial violence.

A Decade of Dialogue and Engagement

As one of several UK institutions with substantial Benin holdings, the MAA has spent years engaged in research, dialogue and partnership with Nigerian stakeholders, including representatives of the Royal Court, artists, scholars and students. Since 2018, MAA curators have undertaken multiple study and liaison visits to Benin City, meeting the Oba, members of the royal court, and state and federal officials.

The University also hosted the Benin Dialogue Group in 2017 and welcomed NCMM and Royal Court representatives to Cambridge in 2021, helping to build the framework that culminated in this restitution.

Professor Nicholas Thomas, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, said the return reflected a shift in global and academic consensus. He noted that support for repatriation had grown “nationally and internationally” over the past decade, adding that the decision had been “keenly supported across the University community”.

Nigeria Welcomes a “Restoration of Dignity”

Olugbile Holloway, Director-General of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments, described the transfer as a turning point in Nigeria’s engagement with European museums.

“The return of cultural items for us is not just the return of the physical object,” he said, “but also the restoration of the pride and dignity that was lost when these objects were taken in the first place.”

Holloway also acknowledged the role of Nigeria’s Minister of Art, Culture, Tourism and the Creative Economy, Hannatu Musawa, and expressed hope that Cambridge’s decision would encourage other institutions to follow suit.

As physical repatriation arrangements progress, the transfer underscores a broader recalibration of how major Western institutions engage with the legacy of colonial collections—one increasingly shaped by restitution, partnership and historical accountability.