A few years ago, US marine officers were left stranded on a muddy field during a high-risk operation in South Korea. Luckily, they had brought generators with them. But the captain was dismayed when the marines—despite their first-class knowledge of equipment maintenance—responded that they could not make the generators work. She was stupefied that the engineers of the world’s most powerful military readily admitted such incompetence. But the officers explained that the generators were broken and could not be fixed because they had been placed under a special warranty by the manufacturers which restricted end-users from repairing the products by themselves. The generators have to be sent back to the manufacturers to be fixed. The crew had to do without electricity. Occurrences such as this has fuelled the rise of the global movement known as “right to repair”.

“Right to repair” is a response to the growing trend of electronics manufacturers making their products needlessly complex to repair through means such as physical design, draconian restrictions on the supply of spare parts and warranty conditions. The movement was born in 2012 when various American and European organisations started to advocate for legislation which would allow users to fix their products with third-party engineers. The movement’s position is perfectly captured by the pioneering right-to-repair site, iFixit, which states that “Once you’ve paid money for a product, the manufacturer shouldn’t be able to dictate how you use it—it’s yours. Ownership means you should be able to open, hack, repair, upgrade it [as you want].”

For years, top technology and electronics manufacturers have been accused of seeking to milk as much profit as possible from consumers from repairing gadgets and/or selling parts to replace faulty ones. In 2011, Apple created a special Pentalobe screw for the iPhone, which makes it very hard for anyone to fix the phone without having inside knowledge of Apple’s very specific engineering processes. Despite the technology giant’s controversial claim that it does not generate any revenue from phone repairs, it was revealed in 2014 that Americans spent a total of $23.5 billion on smartphone repairs within the past seven years, with iPhone repairs taking the lion’s share at $10.7 billion.

“Right to repair” seeks to tackle profiteering in a whole range of industries. In 2018, Americans were revealed to have spent $39.1 billion on replacing over-priced farm equipment parts, with companies like John Deere accused of being at the forefront this exploitation. The pushback against Big Tech is not left to the advocacy groups, though. US Democratic presidential candidates Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren (both long-term consumer rights supporters) have openly thrown their weights behind the movement. While there is much focus on the United States and the European Union, there is one country silently leading the revolution – Nigeria.

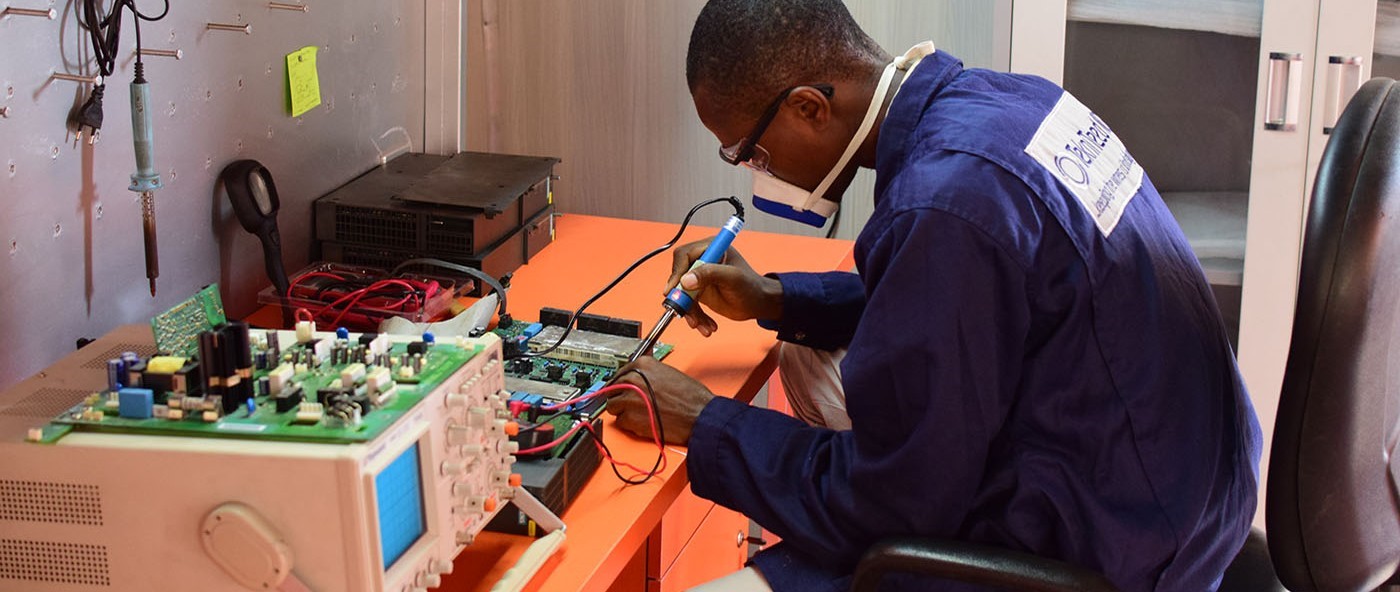

Walking into Arena Market in Oshodi or Computer Village in Ikeja, one is delightfully inundated by the sight of hundreds of electronics repair shops. These engineers do not just resist the warranty, they don’t even read it. The engineers and their customers are not begging anyone for the right to repair, they are not even aware that they have ever been deprived of the right.

Nigeria has a huge repair market populated by third-party technicians skilled in the repair of various kinds of electronic devices. It has been built on a culture of thrift that evolved alongside the expansion of access to electronic goods such as radios and television sets in the 1970s. Unlike Europeans, Nigerians could not afford to walk to the store and buy new television sets when the one at home is broken. And it was also affordable to take the radio, television or eclectic kettle to the neighbourhood electrician to be fixed. Because of high labour costs in America and Europe, it is sometimes preferable to buy a new gadget at times rather than repair a faulty one. Nigeria’s can-fix attitude to electronic gadgets got a big boost with the arrival of the tokunboh era i.e. the largescale importation of used and scrap electronics from Europe and America starting from the late 1980s. Nigerian technicians suddenly had a mountain of gadgets to repair and scavenge for spare parts. It was also a wonderful opportunity to hone their skills and develop a complex value-chain. They were well-poised to help their customers evade the eye-watering cost of high-tech manufacturers when the era of smartphones arrived.

Computer Village Ikeja, Nigeria’s Right to Repair Capital

Computer Village Ikeja is not only the home of pirated software but also a leading light of the global right to repair movement. You can fix a new screen for your iPhone 6 at the Computer Village for as low as N10,000:00. This will set you back by N100,000:00 at any of the Apple authorised resellers in Lagos’ upscale shopping malls. The authorised resellers say entrusting iPhones to the “artisans” in the Computer Village doesn’t bring about lasting solutions as the phones will start to develop all sorts of issues such as overheating because the latter do not use Apple-approved spare parts. The authorised resellers also argue that the guys in Computer Village are not as proficient as their staff who work in air-conditioned offices.

According to Monday, an independent engineer in Computer Village, there is little difference between those hired by representatives of the big tech companies and engineers found in Nigerian markets. Most technicians could become employed by the top electronics companies because they can easily pass the test to get a Trade Test Certificate. The additional expertise acquired through the companies’ specific training programmes is poured back into the independent market by employees who branch out from these companies and go ahead to train their own apprentices with the technical knowledge they have acquired from the tech giants. Thus, the lines between independent technicians and company-hired technicians have become blurred.

For Chidi, an independent technician who fixes generators at Arena Market Oshodi, he is considering leaving his business to work at one of the top generator manufacturing companies to get a stable income. However, he is delaying the move as he fears exploitation by his potential employers. This is the reason many qualified technicians have stuck to going independent despite their sometimes unstable incomes. The big companies are believed to keep a large share of profit while not compensating their workers adequately. This view was somewhat echoed by an anonymous employee of the generator-manufacturing company, Mikano, “Many of us who work in these companies are the same people you see working as independent repair technicians. Some of us eventually leave the companies to start out on our own to stop being exploited.”

Ahmed and Fatai, TV engineers at Arena Market, took offense at having their services compared to that offered by the Nigerian representatives of TV manufacturers, wondering why anyone would patronise their extremely expensive services given much cheaper alternatives. Speaking on why many consumers would rather come to independents, they cited the example of television companies asking for non-refundable charges before even beginning to diagnose the problem with television set. “Even if the company is unable to fix it, your money is gone,” Fatai says. However, with independent engineers, prices are very negotiable to fit your budget. Offering even stauncher criticism of Big Tech, Ahmed and Fatai stated that the big companies are only interested in taking the consumer’s money. They believe the local representatives of electronic manufacturers are fixated on recouping double what they have paid in importation charges through prices charged to repair gadgets.

These technicians get around “knowledge hoarding” and the monopoly of spare parts by buying used, scarp or new electronic gadgets and taking them apart to learn how their internal systems work. They then keep the functioning parts for sale to others who might need them. That way they get hold of the trade secrets the corporations hold on to so dearly. While many Nigerian markets have perfected this art, no other place comes close to Computer Village.

Regarded as Africa’s Silicon Valley, Computer Village is the largest ICT accessory market on the continent, generating well over half a trillion naira annually. It is a dynamic hub of daily transactions where various computer and computer-related devices are sold to buyers at negotiated prices, keeping in line with the conditions of a perfect competition in a free market.

It is commonly said that there are no computer or smartphone parts one cannot find at Computer Village, no matter how outdated, no matter how tiny. You can find third party technicians working from home or at their shops in the computer village who successfully undertake repair jobs that the manufacturers’ representatives will often not accept to do, such as fixing Apple laptops damaged by liquid spills. Gbolahan of IT Solutions who specialises in the repair of Apple laptops says that the authorised Apple resellers don’t accept repairs such as that caused by liquids because they lack the capacity as they are focussed on sales. He added that even in the West, Apple would charge hundreds of dollars to replace a major part of a laptop completely when replacing just a tiny component of the part would have done the job.

There are no doubt very talented technicians in Nigeria’s right to repair movement. The drawback is, compared with doing repairs at manufacturers’ representatives, you may end up handing over your gadget to a complete quack. But the point of the “right to repair” movement is not that there is no risk of being swindled or ill served by third-party technicians. Rather, the argument is that it should be up to the customer who has bought the product to decide whether to take the risk of patronising independent engineers or have to take repairs to the manufacturers no matter how exorbitant the cost is. It is about the right to choose how to repair the products customers have paid for.

On balance, Nigeria’s army of technicians and the associated tokunboh import industry deliver a clearly better alternative to chucking away products or relying on the often unaffordable and sometimes extremely skeletal support services offered by manufacturers’ representatives. It is a vast and extremely diverse industry that gets not only telephones, laptops and television sets working again. When something blows up in microwave ovens, diffusers or electric shavers, or you need new cables to connect them to electric sockets, your technician knows where to source replacement parts, even when your product is the only one of its kind in Nigeria. Every day, thousands of Nigerians are assisted satisfactorily to exercise their right to repair far beyond the western founders of the movement envisaged.