BIG READ – Why Asian-Nigerian Businesses Are So Successful

On being accused of involvement in procurement corruption in parastatals such as Electric Corporation of Nigeria, Nigeria Airways Authority…Chief Okotie-Eboh famously quoted Matthew 13:12, “To those that have, more shall be given…”

Lebanese and Indians own most of Nigeria’s biggest, most successful and longest-running businesses. This is easy to see in most Nigerian cities – Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt, Kaduna, Ibadan, etc. From chains of restaurants to generator and car distributorships, from construction companies to manufacturing, their grip is as wide-reaching as it is unrelenting. They are also on top of many trades such as the import of fish. The biggest real estate project in West Africa, Eko Atlantic City, is being developed by the Chagoury Group, a Lebanese family that also controls Eko Hotel. Why are Asians so successful in Nigeria?

First, let us consider some beer-parlour explanations. Indians, for instance, are very fraudulent. They bribe ever-gullible bank managers to give them big loans and forex allocations. They are basically Ponzi scammers – they spirit the loans out of Nigeria and come back under different names to repeat the cycle. This is at least 97.8% rubbish. There are currently about 35,000 Indians and around 75,000 Lebanese in Nigeria – some of them have been here since the 19th Century. Besides, for every Asian you see defrauding banks, you can find 10 Nigerians doing the same. Many people in the world would laugh really hard if they heard Nigerians complain that we are being out-scammed by Asians.

Nigerians prefer Jollof life. This would have been described as a racist explanation of Asian business success except that fellow Nigerians are the originators and propagators. Indian immigrants are more successful than their counterparts from Germany, England, Greece, Korea, Taiwan etc. in the United States of America. Is this because they are also jollofing like Nigerians? Cultural or ethnic explanations only encourage laziness in place of careful disentangling and analysis of the complex interplay of factors behind any observable phenomenon such as the success of particular groups in business. For instance, Indian is taken as a homogeneous category, but closer enquiry would reveal very important differences in the geographic and ethnic origins of different Indian groups which explain their relative success in business within India and abroad.

The minority Marwari are India’s most successful and wealthiest businesspeople – the top 10 Marwari companies have 6 percent capitalization of the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and constitute a quarter of the Forbes Indian billionaires list. The harsh political and environmental conditions of their Rajasthan homeland fostered a culture of migration, entrepreneurship, risk-taking and a pan-India network of social and business support. In the 12th century, Muslim occupation of their land pushed them from agriculture and cattle breeding into trading. Later, their home region became barren, (Marwari in English means “region of death”) further pushing them out to make a living in far-flung parts of India.

Being migrants who posed no political threats, they were employed to oversee food, ammunition and arms supplies by the emperors of Bengal. The Marwaris thus established a strong presence in the capital of East Bengal, Calcutta which by the 18th century had become the heart of British trade and empire. The Marwaris were well-placed, on the basis of business skills, to make fortunes as agents and brokers to the British. Many Marwari industrial conglomerates were built from modest origins such as the huge profits made from trading jute and cotton during World War I and cottage manufacturing enterprises founded by Marwaris who worked with English industrial firms. Other Indian ethnic groups are not lazy, unique historical accidents have just combined to create and entrench the Marwari dominance in business.

Indians and Lebanese are slave drivers. They work people almost to death for little money. That is the secret of their success. The question is, in a free market with freely available information, why are equally crooked Nigerians who even refuse to pay salaries not exploiting Nigeria’s very slack labour market to also make supernormal surpluses in manufacturing and distribution? Many Nigerians will even swear that “any nation that has a lot of these crooked and exploitative Asians can never progress”.

But Indians are like this at home and abroad, a reflection perhaps of their own extraordinarily frugal origins. In the United Kingdom for instance, where about 35% of Indian households belong to the wealthiest families i.e. those earning over £1,000 a week, in contrast 24% of white British households, Amrit Wilson, member of the South Asia Solidarity Group, pointed out that Indians hire fellow Indians “at very low wages, forced to work in exploitative conditions in Indian-owned businesses”. She made the obvious conclusion that Indian businesses “have grown on the back of this cheap labour”.

Also Read: BIG READ – 2020 – 2030: 15 Nigerians Who Will Shape the Decade (Part 2)

So, what are the reasons for the success of Indian and Lebanese businesses?

1. First-Comer Advantage: Of course, it is our country, but Asians came with a lot of business know-how including trading and manufacturing experience. These matter far more for business success than indigeneity and even capital. India, for instance, has had a longer and denser history of interconnections with the global system of economic production and trade. By the early 1600s, European East Indian companies have set up bases in ports such as Surat, Masulipatnam, Hooghly, building on centuries of trading by coastal regions that saw the movement of grain and cotton in enormous caravan trades overland – Nigerians in this period were mostly trading by barter over very short distances. In the 1700s, new port cities such as Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata emerged. From the 1860s, factory jobs which involved the use of machinery and paid labour increased from about 80 thousand to 2 million.

This rate of growth was higher than the global average, comparable to what occurred in the leading emerging economies of the time such as Japan and Russia. There was nothing even close to this in the economies of Africa or even most of Asia. Clearly, Asians who migrated to Nigeria in the late 17th and 18th centuries brought critical socially coded knowledge of trade and manufacturing with them. The Nigerian competition was very weak and has remained so as a result of policy choices that Nigerian governments have made over the decades. We should also note that it is always the most ambitious or most desperate to succeed among a nation of over 1 billion people that leave their country to other places.

2. Poor economic policies and weak state capacity: We gave ourselves very little chance to learn. From the 1950s, Nigeria adopted economic policies which encouraged mass consumption of imported goods and discouraged domestic agriculture and manufacturing through mainly an overvalued exchange rate first made possible by the export of cash crops and later, oil. In most of Asia, domestic manufacturing developed by making very simple and very cheap goods for vast populations of farmers.

Nigeria imported sophisticated finished goods and expensive, semi-finished inputs to manufacture equally sophisticated goods. What little manufacturing industry Nigeria was able to develop was wiped out by devaluation of the Naira whenever oil prices fell and Nigeria was unable to afford expensive, semi-finished inputs into manufacturing. Nigerian governments also invested in and managed the biggest businesses: this was a major source of corruption and it also deprived a population that had little history of largescale economic organisation the opportunity to learn how to manage modern large enterprises.

Hence, many of the first Nigerians who managed very large businesses were also people who had the opportunity to waste and misuse vast sums of money. While a country like India also had poor protectionist policies like Nigeria until the decisive policy turn-around of the early 1990s, the coincidence of plenty, waste and theft was nowhere as pervasive as in Nigeria. The Nigerian political economist, Opeyemi Agbaje, Founder RTC Advisory Services Ltd., once recalled how his Indian friend would joke “your stupid country sent three of my children to Harvard and Yale Universities”. It would absolutely have been impossible for him to pay American school fees as a senior manager in India, but Nigerian petrol-powered high exchange rate made him the proud father of three Ivy League graduates. The anti-business policy climate meant only the best prepared and most well-resourced i.e. Indians and Lebanese, could withstand the gales of policy havoc.

3. Models of (business) success: Before and after independence, Nigeria didn’t have many models of big national or regional figures who became very rich doing business, especially manufacturing. Quickly, it became clear after independence that the most rewarding enterprise was to seek to control government resources rather than take the risk of becoming a businessperson. And also, most businesspeople were not genuine entrepreneurs but lucky people who were able to access government contracts or a vast array of subsidies. This was quite sensible for very ambitious Nigerians as government actions and economic policies jeopardised businesses. Indians in Nigeria could not become big bureaucrats, governors, senators, party chairmen etc. so they focused on getting better and making a success of the single thing that brought them to Nigeria i.e. making money even if they were also able to exploit the many abuses the system allowed.

4. Pako vs Butter Life: A member of our team remembers his dad taking 12 of them to London on holiday in the late 1970s. He would take the boys to Indian tailors, who remembered their names, to make bespoke suits. The dad was a first-generation graduate; his own dad was an unlettered farmer. He had made a small fortune straddling journalism and politics and trading which was enabled by privileged access to foreign exchange rather than rooted in a productive business in the hands of the second or third generation. In post-colonial Nigeria, university degrees were highly venerated because of the instant access to fabulous material comfort it afforded. So, the Nigerian model of success was not someone who labours hard and persistently to build a business or manufacturing enterprise but someone who instantly got a 3-bedroom flat and Peugeot 504 upon graduation as a modest base to build on.

These comforts were made possible only by unsustainable economic policies such as rapid expansion of well-paid public sector jobs and manufacturing and services employment that depended on highly subsidised foreign exchange based on ever-rising oil prices. On the other hand, among the Marwaris, “establishing a business earns more respect than a university degree and entrepreneurship is strongly encouraged”. Amongst the Marwaris, children imbibe critical traits and skills essential to business success from the businesspeople – parents, kin and friends – who surround them. Even the very rich have their children do holiday jobs in their factories or enterprises. Because of the rentier nature of business and modern incomes in Nigeria, children imbibe mostly consumption habits, a culture of lau lau, from the richest Nigerians.

5. Social Capital: This is a combination of a lot of hard and soft factors, embodied in networks that are in nature simultaneously economic, cultural, ethnic, religious, geographic etc. So, a 16-year-old Indian can get into auto distribution or food manufacturing business by joining an uncle’s business in Lagos. Over the next ten years, he can move across three or four businesses in his sector that are also owned by other Indians. These networks are important for breaking into trades and industries and acquiring the knowledge that are critical to success. Trust, especially an expectation of reciprocity, makes these networks very powerful. Again, the Marwaris provide a good illustration; they have very close business links and intra-group business lending is prevalent. A Marwari businessman easily secures a loan from another with the understanding that it is payable on demand. Marwaris are freer to take risks in business because their networks support people who fall on hard times. This is easy because they have all been trained to do business while suppressing personal egos and not to behave like royalty, no matter how rich they are.

6. Culture: Culture works in two interrelated but distinct ways. First, it helps ethnic groups strengthen business networks that dominate specific niches in the economy e.g. Nigerian Igbos selling spare parts in Lagos. This is banal social capital at work. It could also operate as ethnic or cultural groups preserving worldviews, values, traits etc. that happen to aid success in business generally. The latter requires insulation i.e. the group keeps largely to themselves, preserving the purity of their culture by marrying and socialising almost exclusively with each other, all members adhering to their traditional religion etc. This reinforces shared values and worldviews that are important for ultimate success e.g. laser focus on business, frugality and emphasis on delayed gratification aside from enabling trust and providing an effective mechanism to sanction misdemeanours.

The extra element of insulation turbocharges business success in cases where business acumen or even a thirst for education and excellence is embedded in the group culture. Successful Indian groups have done well in places like the UK and the USA not only through social capital benefits of culture but also by insulating their culture with its focus on hard graft from the more liberal and permissive urban or working-class culture. Flexibility is also essential to success otherwise, insularity may turn out to aid an ethnic community get stuck in low-paid employment such as taxi driving or even crime and dependence on welfare. The Marwaris, for instance, adapted to local conditions of everywhere they migrated to while also preserving their culture. What has really worked for Asians in Nigeria is the social capital effects of culture rather than insularity. Middle-class Nigerian culture to which they are exposed to (as opposed to the culture in Western low-income estates) also values education and personal achievements (even if these are geared towards the fierce competition for rents) and thus poses no threats of consequential dilution.

7. Polygamy: Victor Asemota, an IT expert, in his Twitter thread on the topic advanced polygamy as one of the factors militating against Nigerian business success. This is self-evident. Wealth or capital gets cannibalised amongst several children once a businessman dies. But we do not believe that this is a very important factor. The businessmen while alive, had made the rational choice to train their children to go into professions such as law and possibly, political and government positions, including the military, which put them in a position to earn or distribute huge rents that government policy created.

Think of Lieutenant-Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, who joined the Nigerian civil service and later the Nigerian Army, after Kings College, Lagos and Lincoln College, University of Oxford, with the blessing of his father, Sir Louis Ojukwu, a transport tycoon and one of the richest Nigerians of the era. Many scholars have noted how government policy depleted the huge assets built up by Nigerians involved in the production and trading of export crops through the transfer of export earnings from farmers to bureaucrats in charge of expanding education, the civil service and import-substituting industrialisation, using the instrument of marketing boards. So, why would any reasonable father choose to keep his sons in the productive sectors of the economy and not position them for careers that created and distributed huge rents?

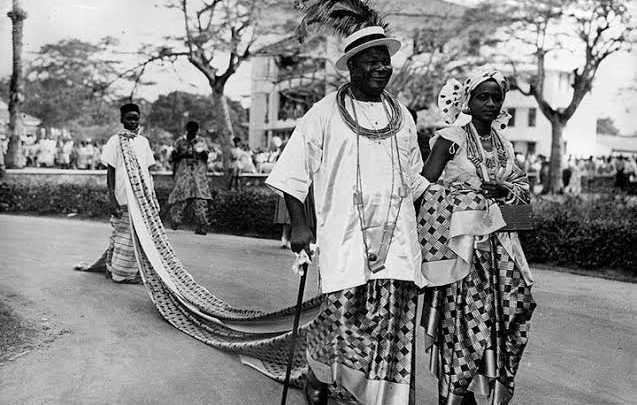

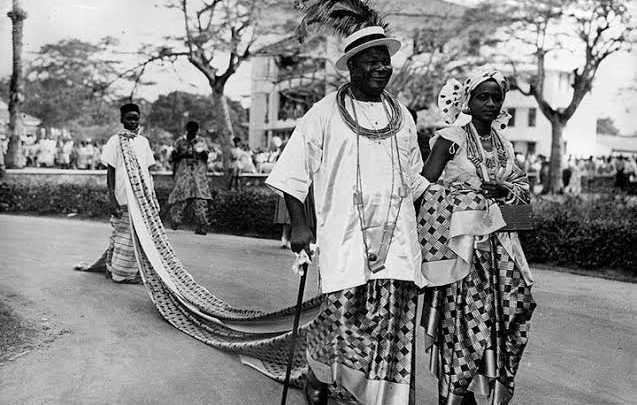

Even major businesspeople were straddling private enterprise and government and political positions where they could accumulate wealth. Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh, a highly gifted businessman who made a string of investments in rubber export and processing, shoemaking, cement production and in establishing a chain of schools was notable example. He later became a Finance Minister in the First Republic through supplementary investment in politics. On being accused of involvement in procurement corruption in parastatals such as Electric Corporation of Nigeria, Nigeria Airways Authority, Nigeria Railways Corporation and Nigeria Ports Authority, Chief Okotie-Eboh famously quoted Mathew 13:12, “To those that have, more shall be given…”. Muslim or Christian, Nigerian businessmen did not need a soothsayer to convince them to send their children after the abundance that government vast interventions in the economy created.

History is not destiny. With the drastic diminution of cushy public sector jobs and private sector employment buoyed by subsidised inputs especially foreign exchange, the explosion in the population of degree-bearing Nigerians and the intermittent liberalisation of the country’s economy (e.g. banking and telecoms) over the last 30 years, Nigerians have come to value entrepreneurship and many have acquired the skills to manage largescale enterprises. They have blocked Asians from occupying and dominating new sectors of the economy. Yet, policy choices continue to reward parasitic behaviour, and unstable and erratic government conduct and policies remain a big disincentive for investing energies in building businesses. Consistent improvement in policy and the business climate will see Nigerians deploying their legendary entrepreneurial drive, long targeted at capturing rents and at small-scale enterprises, to building world-beating conglomerates.